From the earliest days of America, expanding access to education has always been a distinctive feature of national culture. Literacy rates in America largely outpaced much of the rest of the world, and Founding Father John Adams explained that by his day, “A native of America who cannot read and write is…as rare as a comet or an earthquake.”[1] Not even England or France could make a similar claim during this time, so what made America so exceptional when it came to education?

Fundamentally, America’s concern with increasing the amount of people who could read directly corresponded with the widespread desire for additional access to the Bible. The efforts to colonize North America came only after Johannes Gutenberg started the Printing Revolution (mid-1400s) and the Reformation (early 1500s) encouraged for Christians to return ad fontes—to the sources—and read the Scriptures for themselves. Out of these symbiotic movements, translation efforts brought the Word of God to millions of people in their native tongue for the first time. For many, however, this still did not completely allow them to personally study the Bible as they had never been taught to read or write.

In was in the midst of this radical transformation of Western society that religious groups such as the Pilgrims and the Puritans traveled to the New World to practice their religion according to the dictates of their own conscious. In making his argument for American colonization to Queen Elizabeth in 1584, priest and scholar Richard Hakluyt explained that,

We shall, by planting there, enlarge the glory of the gospel, and from England plant sincere religion, and provide a safe and sure place to receive people from all parts of the world that are forced to flee for the truth of God’s word.[2]

When these religious refugees of arrived in America, they carried the Bible and its ideas with them wherever they went. There are repeated instructions throughout concerning the importance of education, specifically the instruction of the next generation. In Psalm 119:66, King David asks God to, “Teach me good judgment and knowledge,” and Proverbs 22:6 instructs parents to, “Train up a child in the way he should go.” This second verse especially influenced the actions of the early colonists when they began to settle the New England area.

In 1642, the General Court of Massachusetts passed the first public education law in North America. It stipulated that schools be set up for both, “boys and girls,” in order to increase, “their ability to read and understand the principles of religion.”[3] Five years later, in 1647, Massachusetts, further clarified the intention behind the foundation of public education by passing what became known as the Old Deluder Satan Act. The preface explained that schools were necessary because:

It being one chief project of that old deluder, Satan, to keep men from the knowledge of the Scriptures, as in former times keeping them in an unknown tongue, so in these later times by persuading the use of [foreign] tongues, that so at least the true sense and meaning of the original might be clouded with false glosses of saint-seeming deceivers; and that learning may not be buried in the graves of our fore-fathers in Church and Commonwealth, the Lord assisting our endeavors.[4]

The law goes on to explain that, “it greatly concerns the welfare of the country that the youth thereof be educated not only in good literature, but in sound doctrine.”[5] This mattered so much that Massachusetts required that all teachers must give, “satisfaction according to the rules of Christ,” before being hired.[6]

With the schools having been established, learning materials now needed to be provided. Political philosopher John Locke noted that students learned to read by following “the ordinary road of the Hornbook, Primer, Psalter, Testament, and Bible.”[7] A hornbook was a simple flat piece of wood with the alphabet and the Lord’s Prayer on it as a child’s first reading lesson. After that came a primer which taught more advanced words, and included significant amounts of religious instruction for the students. The main text used in early America for well over a hundred years was the New England Primer.

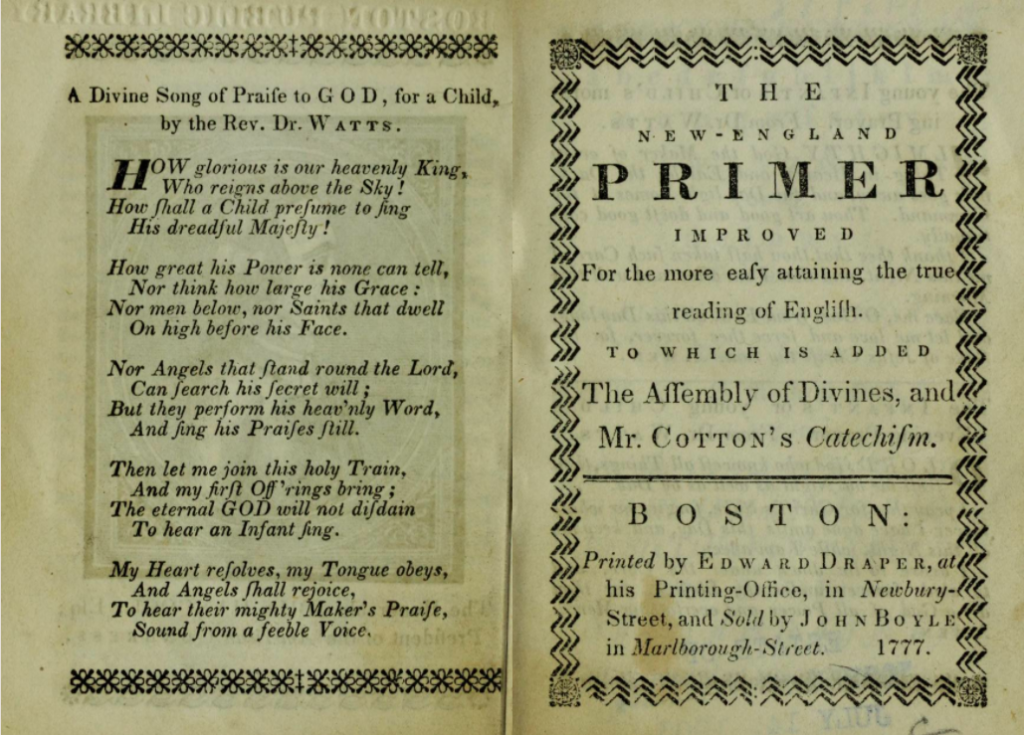

The New England Primer was first published in Boston during the late 1680s by a printer named Benjamin Harris who had left England having been severely oppressed for his religious writings.[8] Based on similar textbooks used in England, the Primer was meant to serve as the first step in teaching children to read the Bible and abide by its teachings. The multitude of sections all aimed to inculcate pious living and catechize students in religious doctrine.

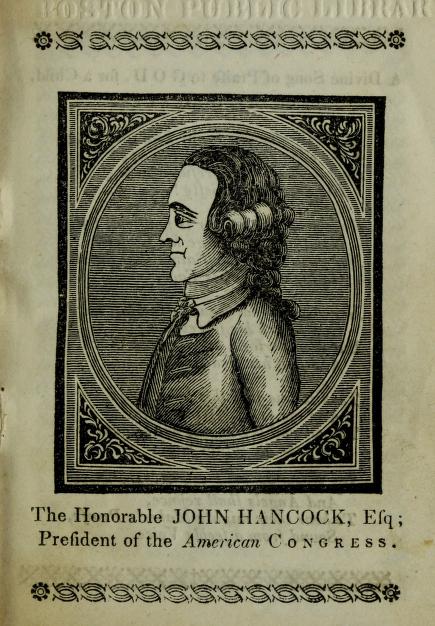

By the time of the American War for Independence the New England Primer had become a cornerstone in education. The first edition printed after the Declaration of Independence was in 1777 and replaced the image of King George III with an engraving of John Hancock as president of the Continental Congress. After a few prayers and a list of words up to five syllables, the Primer includes its first “Lesson for Children” which instructs students to, among other things: “Pray to God. Love God. Fear God. Serve God.”[9]

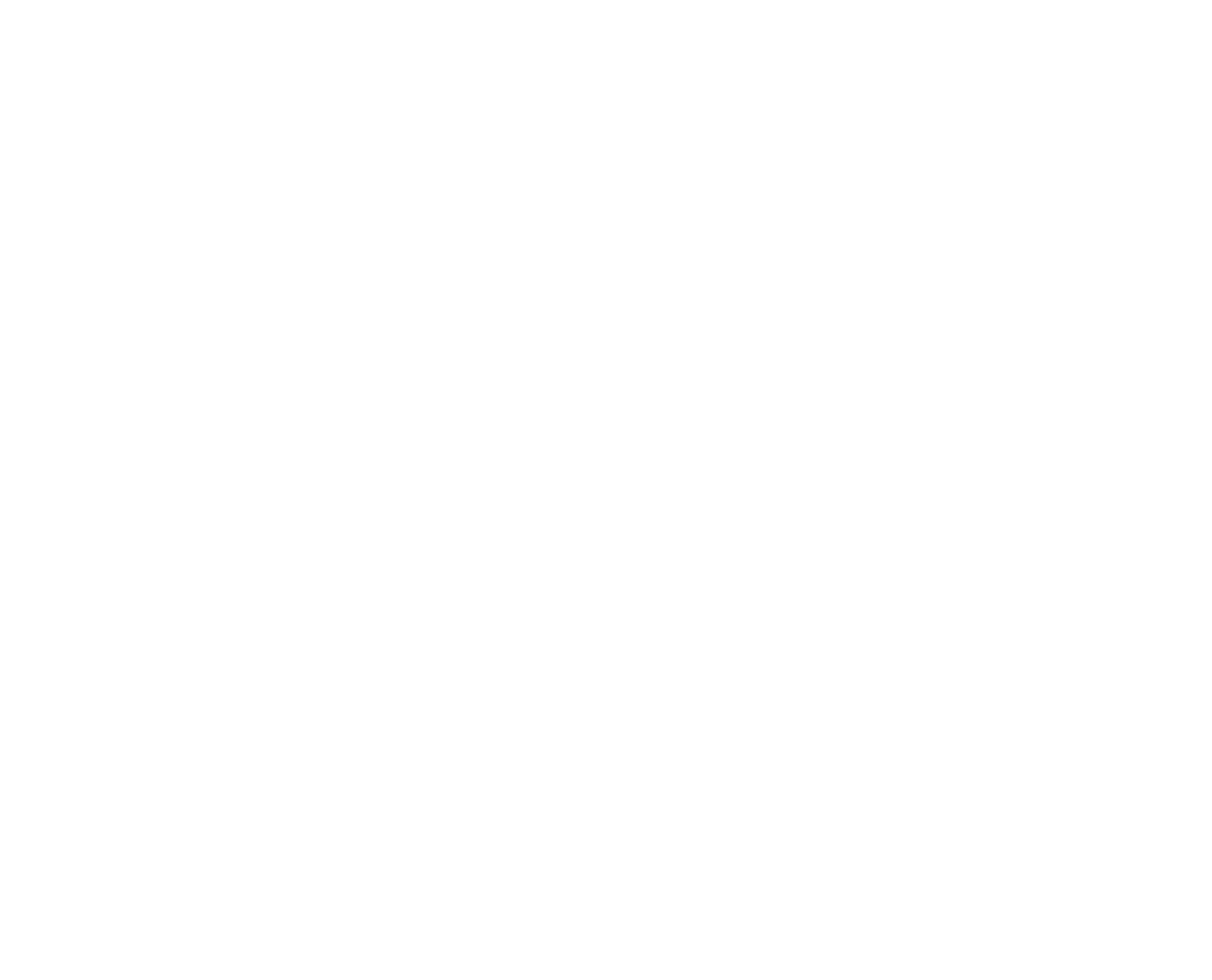

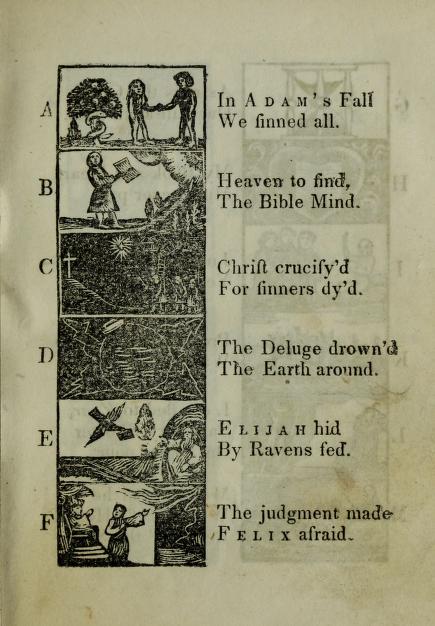

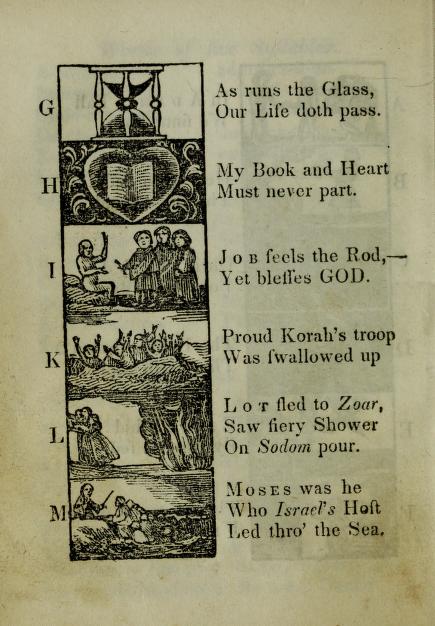

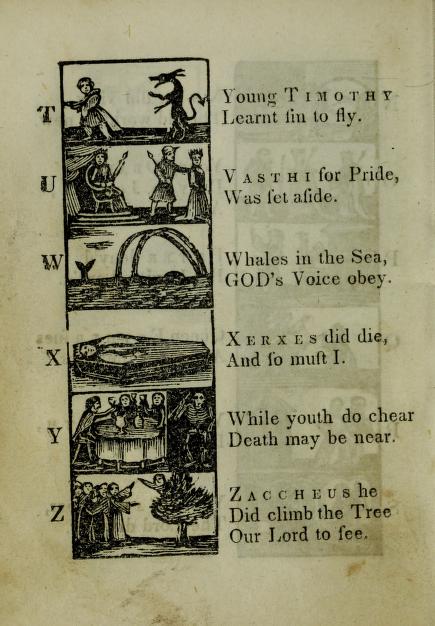

In perhaps its most famous section, the Primer then includes a picture alphabet featuring scenes either from or inspired by the Bible.

Practically every section of the Primer includes direct quotes from Scripture, paraphrases of passages, or religious poetry from authors such as Isaac Watts. The Primer likewise includes the story of the martyrdom of John Rogers who, “died courageously for the gospel of Jesus Christ.”[10]

The largest section, which sometimes served as the final exam, was the Shorter Westminster Catechism which consists of over one hundred questions on the Bible, doctrine, and theology. To illustrate the level of understanding expected from students, here is one of the earlier questions:

Q. 36. What are the benefits which in this life do accompany or flow from justification, adoption and sanctification?[11]

The expected answer reflects a depth of study which are rarely seen in even private Christian schools, much less in public schools:

A. The benefits which in this life do accompany or flow from justification, adoption and sanctification, are assurance of God’s love, peace of conscience, joy in the Holy Ghost, increase of grace, and perseverance therein to the end.[12]

Many Founding Fathers believed the New England Primer to be essential for students. For example, Samuel Adams had it printed for students in Massachusetts,[13] Noah Webster provided it in Connecticut,[14] and Benjamin Franklin published an edition in Pennsylvania.[15] Millions of copies were printed and, despite its region-specific name, the New England Primer was used in schools throughout the entire United States.[16] It remained a common textbook for learning how to read until the beginning of the 20th century and remains in print today with thousands being sold annually.[17]

The American Journey Vault houses dozens of New England Primers from various years including early printings of the 1777 edition. You can read the whole text online here.

[1] John Adams, “A Dissertation on the Canon and Feudal Law,” August, 1765, The Works of John Adams, ed. Charles Francis Adams (Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1856), 3.465,

[2] Richard Hakluyt, A Discourse Concerning Western Planting Written in the Year 1584 (Cambridge: John Wilson and Son, 1877), 158. Here.

[3] See, entry for June 14, 1642, Nathaniel B. Shurtleff, Records of the Governor and Company of the Massachusetts Bay in New England (Boston: William White, 1853), 2.6-7. Here.

[4] The Book of the General Lawes and Libertyes Concerning the Inhavitants of the Massachusets (Cambridge: General Court, 1660), 70. As reprinted in 1995, here.

[5] The Book of the General Lawes and Libertyes Concerning the Inhavitants of the Massachusets (Cambridge: General Court, 1660), 71. As reprinted in 1995, here.

[6] The Book of the General Lawes and Libertyes Concerning the Inhavitants of the Massachusets (Cambridge: General Court, 1660), 71. As reprinted in 1995, here.

[7] John Locke, “Some Thoughts Concerning Education,” 1693, The Works of John Locke (London: Sine Nomine, 1812), 9.148.

[8] Paul Leicester Ford, The New England Primer: A History of its Origin and Development (New York: Dodd, Mead, and Co., 1897), 12-14, 16. Here.

[9] “A Lesson for Children,” The New-England Primer Improved (Boston: Edward Draper, 1777), here.

[10] “The Shorter Catechism,” The New-England Primer Improved (Boston: Edward Draper, 1777), here.

[11] John Rogers, “Advice to his Children,” The New-England Primer Improved (Boston: Edward Draper, 1777), here.

[12] John Rogers, “Advice to his Children,” The New-England Primer Improved (Boston: Edward Draper, 1777), here.

[13] Paul Leicester Ford, The New England Primer: A History of its Origin and Development (New York: Dodd, Mead, and Co., 1897), plate xxiv, following 300.

[14] Emily Ford, Notes on the Life of Noah Webster (New York: Privately Printed, 1912), 2.532.

[15] Paul Leicester Ford, The New England Primer: A History of its Origin and Development (New York: Dodd, Mead, and Co., 1897), 310, 313.

[16] Stephanie Schnorbus, “Calvin and Locke: Dueling Epistemologies in The New England Primer, 1720–1790,” Early American Studies, 8 (Spring 2010): 250–287; Paul Leicester Ford, The New England Primer: A History of its Origin and Development (New York: Dodd, Mead, and Co., 1897), 19.

[17] For examples of these reprints see, Paul Leicester Ford, The New England Primer: A History of its Origin and Development (New York: Dodd, Mead, and Co., 1897), 16-19, 300; The New England Primer: Twentieth Century Reprint (Ginn & Company, 1900), Foreword; George Littlefield, Early Boston Booksellers, 1642-1711 (Boston: The Club of Odd Volumes, 1900), 158; Sterling Brewer, “Some Old-Time Schoolbooks,” The Christian Advocate (July 28, 1911), 22; Paul L. Ford, New England Primer (Teachers College Press, 1962); The New-England Primer (Aledo, TX: WallBuilder Press, 1991).