Despite the Declaration of Independence’s clear statement that, “all men are created equal,” modern revisionist historians have nevertheless suggested the American Revolution was exclusively for white men. One academic recently denounced the Founding Fathers, claiming that they, “buried prejudice deep in the cornerstone of the new American republic in 1776.”[1] Similarly, the New York Times’ 1619 Project plaintively asks, “Why can’t we teach this?”[2] However, these revisionists repeatedly either forget, minimize, or ignore the monumental efforts and widespread participation of black patriots in the Revolutionary struggle who fought and died shoulder to shoulder with whites to secure independence.

The black patriots who served in the largely integrated Continental Army were vital in setting the stage for unprecedented emancipations across the newly forged nation.[3] Indeed, without the black soldiers who served alongside white patriots in George Washington’s army, independence may have never been achieved. On average, black soldiers served nine times longer than the white soldiers, and by the end of the war, the most experienced men in the America were the African American soldiers.[4] In fact, the black First Rhode Island Regiment was so effective in battle that it was said on the floor of Congress that, “no braver men met the enemy in battle.”[5]

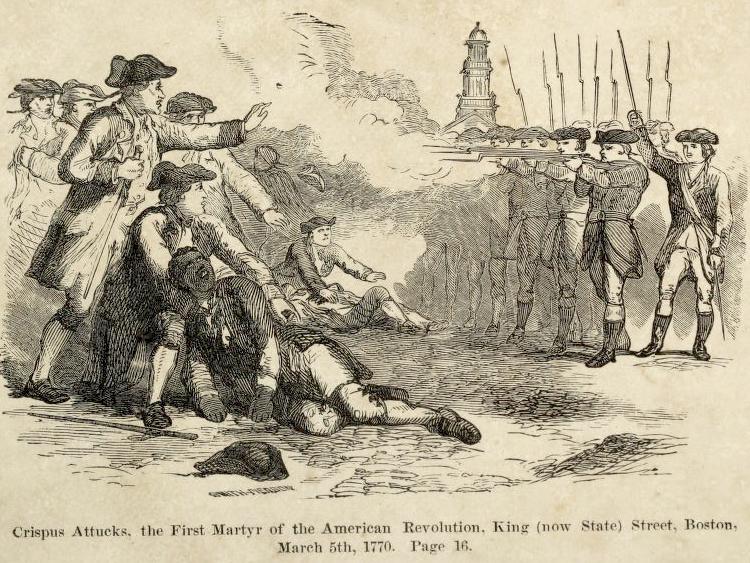

During the opening stages of the American War for Independence, black Americans played prominent roles in resisting British tyranny. Crispus Attucks led the Americans during the Boston Massacre and was the first one killed by the British soldiers when they fired upon the crowd.[6] Judge Thomas Dawes, a notable patriot leader in Boston, declared that the actions of Attucks and the others, “must be numbered among the master-springs which gave the first motion to a vast machinery—a noble and comprehensive system of national independence.”[7] Similarly, the Americans who confronted the British at the Battle of Lexington were from an integrated church which included black Americans such as Prince Estabrook who was wounded in the battle.[8]

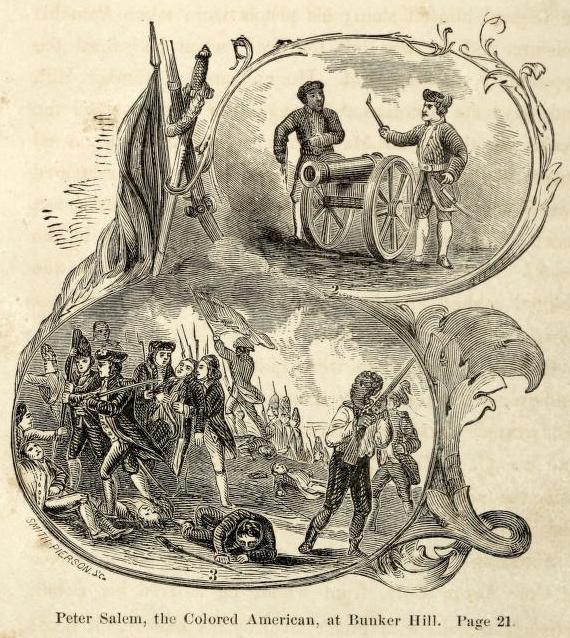

Furthermore, many of the black soldiers in the Continental Army were widely recognized for their bravery, courage, and dedication to the cause of liberty. For example, the hero in the Battle of Bunker Hill was a black man named Peter Salem.

Salem had been born a slave around 1750 and lived for most of his life in Framingham, Massachusetts. Originally owned by Capt. Jeremiah Belknap, he was sold to Maj. Lawson Buckminster shortly before the Revolution began.[9] Buckminster, however, emancipated Salem who quickly joined the military in order to fight for independence. On June 17, 1775, Peter Salem distinguished himself during the Battle of Bunker Hill by killing the British commander, Major John Pitcairn, stalling the English advance and allowing more time for the American retreat, effectively saving an entire American unit.[10]

One veteran of the Revolutionary War who had fought alongside Salem related the story that:

The Major had passed the storm of our fire without, and had mounted the redoubt, when, waving his sword, he commanded, in a loud voice, the ‘rebels’ to surrender. His sudden appearance and his commanding air at first startled the men immediately before him. They neither answered nor fired; probably not being exactly certain what was next to be done. At this critical moment, a negro soldier stepped forward, and, aiming his musket directly at the major’s bosom, blew him through.[11]

Another eyewitness, Samuel Swett, who was present at the battle similarly recalled that:

Among these mounted the gallant Major Pitcairn, and exultingly cried ‘the day is ours,’ when a black soldier named Salem, shot him through and he fell. His agonized son received him in his arms and tenderly bore him to the boats.[12]

Peter Salem’s courageous heroism earned him a personal audience with George Washington.[13] The death of Maj. Pitcairn was immortalized by painter John Trumbull in 1786 who was at the battle himself.[14] In that painting, Peter Salem can be seen in the lower right-hand corner having just shot down the British officer.[15]

The American forces at the Battle of Bunker Hill included many more black patriots, including heroes such as Cain Bowman, Henry Hill, Titus Coburn, Alexander Ames, Barzilai Lew, Cato Howe, Seymour Burr, and Jeremy Jonah.[16] Another black soldier, Salem Poor, also distinguished himself, and the official military recommendation signed by fourteen witnessing officers explained that:

We declare that a Negro Man called Salem Poor…behaved like an experienced officer as well as an excellent soldier; to set forth particulars of his conduct would be tedious. We would only beg leave to say, in the person of this said negro centers a brave and gallant soldier. The reward due to so great and distinguished a character we submit to the Congress.[17]

Without men like Peter Salem and Salem Poor bravely resisting the British military in the opening days of the Revolutionary War, the story of America might have gone quite differently.

Peter Salem served in the Continental Army for a total of seven years under the command of Capt. John Nixon and Capt. Simon Edgell.[18] Throughout his service, he fought in the battles of Harlem Heights, Trenton, Saratoga, and Stony Point.

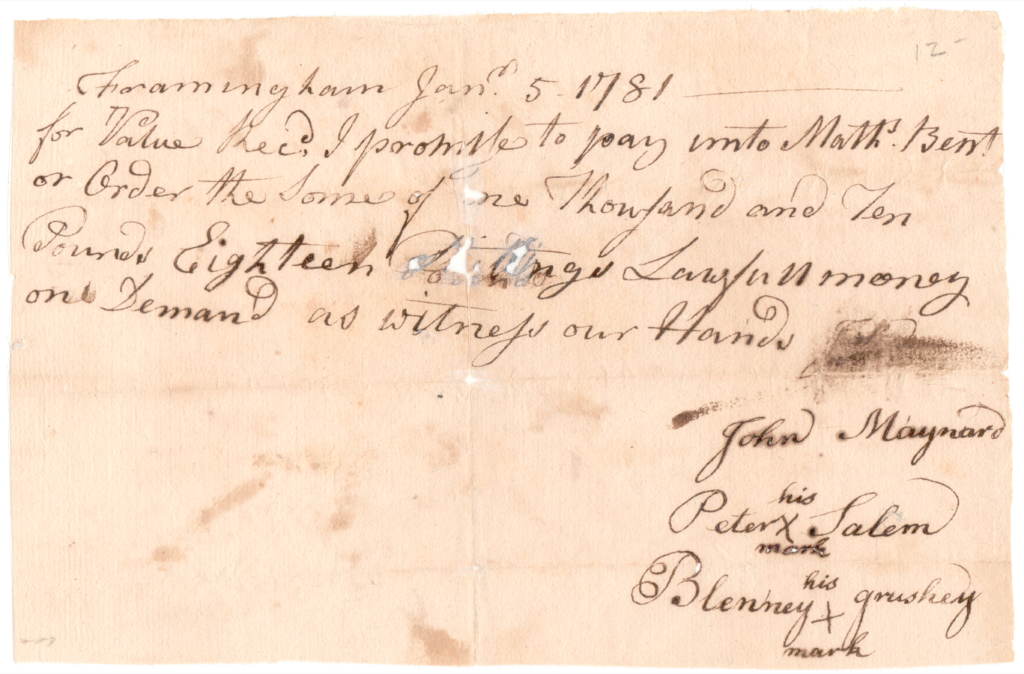

Stored in the American Journey Vault is the only known document signed by Peter Salem. Dated January 5, 1781, which was during the closing phase of the Revolution, this document sees Salem, alongside two other men, promising to pay a massive sum of 1,010 pounds and 18 shillings. Because Salem had not learned to write at this point in his life, he signs the agreement by marking it with an “X” which was a common practice at the time.

In full, the document reads:

Framingham Jan. 5. 1781

For Value Rec’d [received] I promise to pay unto Matt’ Bent on Order the Some of one Thousand and Ten Pounds Eighteen Shillings Lawful money on demand as witness our Hands.

John Maynard

Peter Salem X his mark

Blenney Grushey X his mark

Although not much is known about the context surrounding this document specifically, the signature below Salem’s is the mark of a man named Blenney Grushey which is also spelled Blaney Grushy. He had been a slave to Col. Micah Stone in the same town as Salem before also being freed. Seemingly, Grushy and Salem joined the army together and the two men fought alongside each other in the Battle of Bunker Hill.[19]

[1] Robert G. Parkinson, Thirteen Clocks: How Race United the Colonies and Made the Declaration of Independence (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2021), 3.

[2] Nikita Stewart, “Why Can’t We Teach This,” The New York Times (August 18, 2019), 3.

[3] Benjamin Quarles, The Negro in the American Revolution (Williamsburg: The University of North Carolina Press, 1961), 71-72.

[4] Michael Lanning, Defenders of Liberty: African Americans in the Revolutionary War (New York: Kensington Publishing, 2000), 176-177.

[5] Tristam Burges quoted in, William Lloyd Garrison, The Loyalty and Devotion of Colored Americans in the Revolution and War of 1812 (Boston: R. F. Wallcut, 1861), 8.

[6] William Nell, Colored Patriots of the American Revolution, (Boston: Robert F. Wallcut, 1855), 16. Here.

[7] Thomas Dawes, “March 5, 1781. On the Boston Massacre,” in James Spear Loring, The Hundred Boston Orators Appointed by the Municipal Authorities and Other Public Bodies from 1770 to 1852 (Boston: John P. Jewett and Company, 1853), 143. Here.

[8] Jonas Clark, The Fate of Blood-Thirsty Oppressors and God’s Tender Care of His Distressed People. A Sermon, Preached at Lexington, April 19, 1776. To Commemorate the Murder, Bloodshed and Commencement of Hostilities Between Great-Britain and America in that Town, by a Brigade of Troops of George III under Command of Lieutenant-Colonel Smith, on the Nineteen of April 1775. To Which is Added A Brief Narrative of the Principal Transactions of That Day (Boston: Powers and Willis, 1776), 5; J.T. Headley, The Chaplains and Clergy of the Revolution (New York: Charles Scribner, 1864), 79; John Weiss, The Life and Correspondence of Theodore Parker (London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts and Green, 1863), 1.12; Elias Phinney, History of the Battle at Lexington, On the Morning of the 19th April, 1775 (Boston: Phelps and Farnham, 1825), 27; Frank Coburn, The Battle on Lexington Common, April 19, 1775 (Lexington: Frank Coburn, 1921), 33.

[9] William Barry, History of Framingham, Massachusetts (Boston: James Munroe and Company, 1847), 64. Here.

[10] Emory Washburn, Historical Sketches of the Town of Leicester, Massachusetts (Boston: John Wilson and Son, 1860), 266-269, 308, Here; William Nell, The Colored Patriots of the Revolutionary War (Boston: Robert Wallcut, 1855), 21.

[11] George Livermore, An Historical Research Respecting the Opinions of the Founders of the Republic on Negroes as Slaves, as Citizens, and as Soldiers (Boston: John Wilson and Son, 1862), 119. Here.

[12] Samuel Swett, Historical and Topographical Sketch of Bunker Hill Battle (Boston: Samuel Avery, 1818), 247.

[13] Emory Washburn, Historical Sketches of the Town of Leicester, Massachusetts (Boston: John Wilson and Son, 1860), 266-269, 308, Here; William Nell, The Colored Patriots of the Revolutionary War (Boston: Robert Wallcut, 1855), 21.

[14] George Livermore, An Historical Research Respecting the Opinions of the Founders of the Republic on Negroes as Slaves, as Citizens, and as Soldiers (Boston: John Wilson and Son, 1862), 119. Here.

[15] Some modern academics deny that the black soldier depicted by Trumbull was Salem and that it instead was a slave of Thomas Grosvenor. This more recent suggestion denies the more than two centuries worth of attribution by hundreds of historians and witnesses and is based more upon speculation than historical fact.

[16] John Davis, An Oration, Pronounced at Worcester, (Mass.) on the Fortieth Anniversary of American Independence (Worchester: William Manning, 1816), 9. Here.

[17] Quoted in, Sarah Loring Bailey, Historical Sketches of Andover, Massachusetts (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1880), 324. Here.

[18] Joseph Wilson, Black Phalanx: A History of the Negro Soldiers of the United States (Hartford: American Publishing Company, 1890), 38. Here.

[19] William Barry, History of Framingham, Massachusetts (Boston: James Munroe and Company, 1847), 64. Here.