Christmas time in the trenches is never pretty, and the Christmas of 1914 for French, English, German soldiers was no exception. Upon beginning the war, everyone believed it would be over before Christmas. Yet they were locked in a stalemate. All through December and the long months before it, soldiers slogged through thigh-high water in slippery trenches, wondering when the war would end and how many of them would die before it did. Enemy bullets tore the air above men’s heads as they slipped in the mud and froze. In some places, the trenches were mere yards apart, making it possible for the opposing sides to shout at each other, or raise makeshift signs reading “Missed!” or “Left a bit!” after a round of fire.1 The occasional pauses in fire only added anxiety to misery. To an anxious soldier’s imagination, every miniscule sound was a creeping enemy.

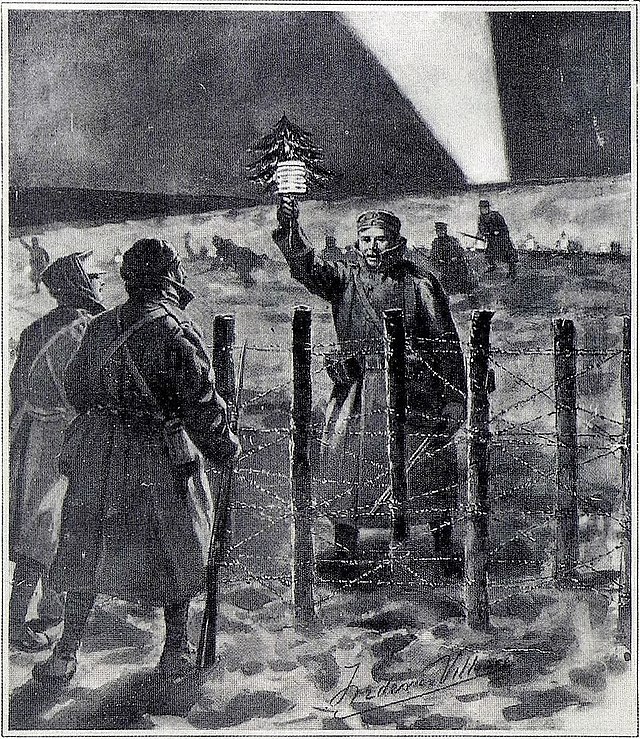

Despite this bleakness (and possibly because of it) soldiers on both sides did their best to decorate the ditches they lived in for the Christmas season. Some of the French and English dragged pine bows into their entrenchments, using them as seasonal garlands. The Germans managed to set up a few Christmas trees tall enough to be seen by the English over No Man’s Land. These trees were decorated with the colored paper bands from their cigars and cigarettes, and any other colorful paper scraps they could get their hands on.2 The German officers expressed annoyance when the English fired upon these trees, insisting that they were an almost sacred part of the holiday.3

As Christmas drew near, soldiers on both sides received gifts from friends and family. These gifts included much needed mittens, scarves, sweaters and cakes. The men that received cakes cut them into gingerbread soldiers, enacting mock battles before eating them.2 Both sides included many young men who were spending their first ever Christmas away from home. The German and English rulers understood this, and did what they could to alleviate suffering. Silver and brass tins often adorned with a cameo of Princess Mary were sent to every English serviceman. They contained a photograph of the princess, a card, tobacco, pencils, sweets and spices.4 German ranks received either a pipe adorned with the profile of Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm, a box of cigars, or a wooden cigar case.5 On Christmas Day, professional French actors among the ranks put on comedy shows. Up and down the Western Front peals of laughter offered a little respite to cold and tired soldiers.2

Various leaders, religious and secular, had attempted to create an official truce over Christmas, but their attempts had failed. It appeared that the monster of war was ungovernable, even for just one day. Despite this, we sometimes find the power of everyday people greater than their rulers.

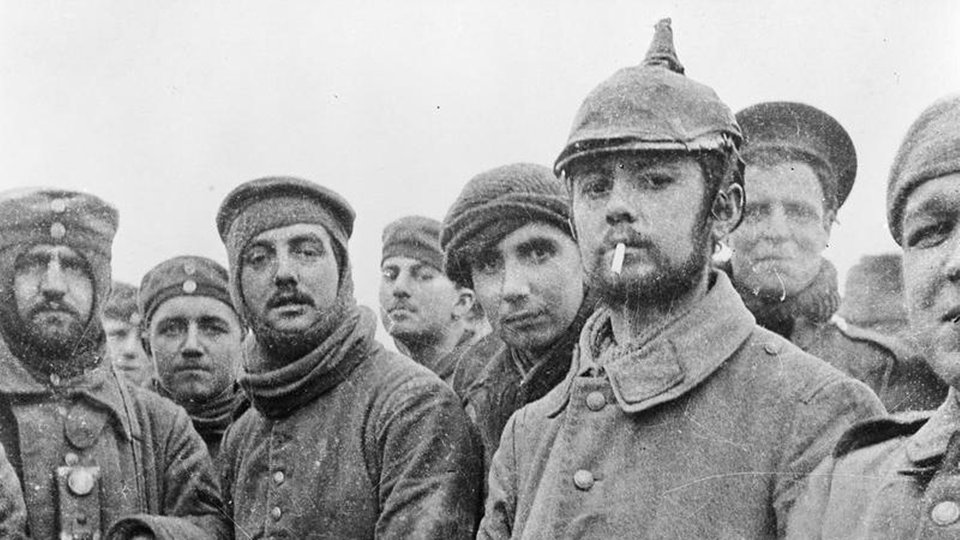

In one trench, English soldiers shouted “Merry Christmas!” over No Man’s Land. The German soldiers, in return, offered a truce by shouting back, “Don’t shoot until New Year’s Day!”. The next morning was misty. English and French soldiers tentatively crept over the top of their embankments without their guns, half expecting to be shot. As the fog cleared they discovered the Germans doing the same.The soldiers met in the middle and shook hands. It wasn’t long before they were swapping jokes and news of the war. Gifts from home were traded, and pictures were taken to commemorate the event.6

The American Journey Experience recently acquired a letter written by a German soldier by the name of Otto Hahn to his wife Edith about the events of the “Christmas Truce”. Though Otto was not a direct participant in the truce, his insight is invaluable. To quote Otto:

“I am afraid I shouldn’t even talk about it, I am convinced the senior officers are suppressing it, but it is true: even our soldiers in the trenches celebrated Christmas. Who knows just how it began? A Bavarian rifleman started it, after the British across the way shouted Merry Christmas when they saw our men raising a Christmas tree on a pole out of the trench. The Bavarian rifleman crawled forward and stared at the English in their trench, or maybe he crawled forward just a little and they encouraged him to come closer. He came back with cigarettes and tobacco. One believed him; he went back again and returned with several Scottish Highlanders…who went all the way to our trenches. Our men joined them. Not a shot was fired. Cigarettes were smoked, candles were placed on the edge of the trenches; they spoke with one another. They didn’t chat only yesterday, but today as well. Officers from our regiment crossed over and the troops came out in throngs. The war was suspended. The Christmas peace had done it. Today not a shot was fired here, not tonight, either. It was a public peace that lasted all the more because everybody had expected the opposite. My machine gunners tell me there probably won’t be any shooting tomorrow either. The British apparently said they were to be relieved by the French. It’s a good thing our men will be relieved as well. It’s hard to decide whether to be happy or outraged by all this. For my part, I am deeply happy about this one-day peace. I have to tell my men that it is not right, even on Christmas Day. That it is dangerous, etc., but deep inside, I think it is beautiful. But what luck that they will be relieved. It would be hard to shoot men, to beat them to death with the butt of your rifle, to run them through, after you just exchanged cigarettes and food.”8

While far from official or universal, there are dozens of letters and diary entries documenting similar events up and down the Western Front. Most of these unofficial ceasefires served as times for the mass burial of their dead. Each side would spend hours laboring to dig shallow communal graves. Sometimes, special permission was granted to approach the very edge of enemy lines to retrieve fallen soldiers. Despite the solemn nature of these burials, not all the events of the “Christmas Truce” were as serious. In some places, German and English troops took turns singing Christmas carols to each other, including “Good King Wenceslas” and “Silent Night”. A few letters even record a football match that took place on No Man’s Land.7 According to a letter, the Germans won the game and the teams exchanged hats. In one location, the Germans brought a barrel of alcohol to share, and in another an English soldier cut buttons from a German’s uniform as a memento. Overall, spirits were high, and soldiers described their sworn enemies as “amicable”.9

Some of these treaties lasted only through Christmas Day, others spanned Christmas through New Years Eve. Either way, at the end of the ceasefire,both sides returned to their trenches and resumed the work of death, downing the men they had befriended the day before. At the end of the truce one Frenchman wrote “(f)or a time all was silent”.“Then we began to try to kill each other again, and the man who offered the first box of cigars to a French soldier fell dead beside me–but, after all, it was a bit of Christmas.”2

Over the course of the following year, papers collected letters and testimonies of this event. In large part, we owe our knowledge of these Christmas truces to the articles written for the 1915 Christmas season. The events seemed to have encouraged hope for the future and reignited a spark of humanity. To quote the article “Christmas in the Trenches” by The Pensacola Journal, “During the coming holidays it is expected that these same scenes will be repeated, and it may be that in the meetings a little prayer for the ending of the carnage may be said and that ere long the Angel of Peace may spread her white wings over the men in the trenches and make the Christmas theme of ‘Peace on earth, good will to men’ a full reality to all the world.”2 The humanity, charity and trust displayed in those fleeting moments of peace continues to inspire a renewal of the Christmas spirit. It serves as an example that with courage and hope, everyday people (even those in the worst of circumstances) can overcome the greatest challenges this world has to offer.

Works Cited

1. Chris. “The Christmas Truce: A General Overview.” Christmas Truce, Operation Plum Puddings, 9 May 2023, www.christmastruce.co.uk/the-christmas-truce-a-general-overview/.

2. “Christmas in the Trenches.” The Pensacola Journal, 10 Dec. 1915.

3. Brown, Malcolm, and Shirley Seaton. Christmas Truce, Pan Macmillan UK, S.l., 1984, p. 76.

4. “Princess Mary Christmas Box.” Royal Cornwall Museum, 10 Nov. 2018, www.royalcornwallmuseum.org.uk/citizen-curator-objects/princess-mary-christmas-box

5. Weintraub, Stanley. Silent Night: The Remarkable Christmas Truce of 1914. Simon & Schuster, 2014, p. 13.

6. “Yet There Was a Christmas Truce.” The Chicago Herald, 2 Jan. 1915.

7. Chris. “The Football Match.” Christmas Truce, Operation Plum Puddings, 9 May 2023, www.christmastruce.co.uk/christmas-truce-the-football-match/.

8. Hahn, Otto. “WWI Christmas Truce.” Received by Edith Hahn, 25 Dec. 1914.

9. “A Sobering Aspect of the Christmas Truce : 25 December 1915.” Western Front Association, www.westernfrontassociation.com/world-war-i-articles/a-sobering-aspect-of-the-christmas-truce-25-december-1915/. Accessed 16 Dec. 2024.