This pocket watch was made in London sometime either in the late sixteenth or early seventeenth century and owned by the famous Myles Standish who journeyed with the Pilgrims to the New World in 1620.

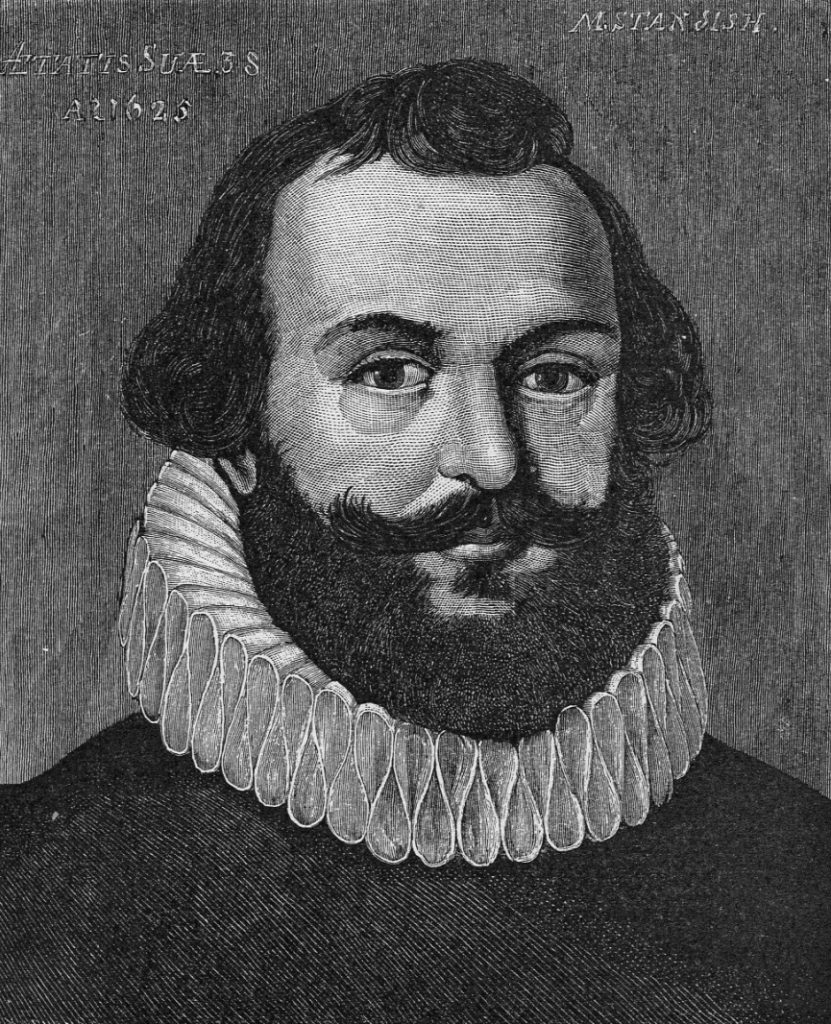

Out of all the people who came across the Atlantic to America on the Mayflower in 1620, few remain as well-known as Captain Myles Standish. Standish, however, was not technically a Pilgrim in the same sense as others such as William Bradford or William Brewster were. The church of religious dissenters living in Holland understood that they could not make the journey alone and would need assistance from individuals with particular skills which they themselves lacked. Therefore, as they assembled the crew who would assist them in their colonization efforts they asked the military veteran Myles Standish, who had served in the English army while stationed in Holland, to act as their military commander.

Standish’s family history was replete with remarkable ancestors including two knights, a military commander who fought at the Battle of Agincourt, and even one who served as a bishop.[1] This prestigious family background meant that he was, “heir-apparent unto a great estate of lands and living,” but which was “surreptitiously detained from him” on non-existent grounds.[2] Therefore, Myles Standish was forced to provide for himself in another way. Likely inspired by the brave deeds of his forbearers, Standish joined the British military and fought alongside the Dutch Rebels in Holland against Spain during the undeclared Anglo-Spanish War.[3]

Although his service history while in Holland is somewhat murky he decided to remain in the country after England signed the Treaty of London in 1604 and the Twelve Years Truce ended hostilities brought peace between Spain and the Dutch Republic in 1609. By 1620, Standish and his wife live in Leiden and have evidently met the exiled Separatist church led by pastor John Robinson and Elder William Brewster who had come to the city around 1608.

Despite deciding to not join their religious sect, he nevertheless became quite attached to the group and, upon being asked, “resolved to cast in his lot with theirs and share their enterprise to America.”[4] Henceforth, Standish became the Pilgrim’s “captain and military commander” who would protect this band of meek religious dissidents in a new and dangerous world.[5]

Upon arriving in the New World, Standish’s experience proved invaluable almost immediately. After signing the Mayflower Compact, he led the first expedition off of the Mayflower in late November.[6] Along with Elder William Brewster, Standish was one of the few healthy individuals during that first devastating winter. William Bradford explained that it was to Standish that, “myself and many others were much beholden in our law and sick condition.”[7] The captain, Bradford continued, was, “not at all infected either with sickness or lameness.”[8] Standish soon became the go-to agent for the Pilgrims and was sent out repeatedly to handle whatever business the Plymouth settlement might have with the surrounding native tribes or other colonies as the case may be.[9] Throughout his many mission amongst the native tribes, Standish quickly began learning some of the languages and was known by the people of Plymouth as, “the best linguist amongst us.”[10]

In 1623, however, some of the other tribes in the area began plotting to launch a surprise attack upon Plymouth.[11] The ostensible reason for this sudden and drastic scheme was that the small and ill-behaved nearby Wessagusset Colony, founded in 1622 by Thomas Weston, had stolen some corn from a local tribe.[12] Since its settlement, this colony had been troublesome not only to the natives but to Plymouth colony as well, even going so far as to steal food from the Pilgrims too.[13] The situation was so desperate for Weston’s colony that some of the colonists traded the shirts off their backs and became servants or slaves to the Indians in order to get some corn.[14] At one point the Wessagusset Colony had written to Plymouth to see if they would join in an attack against the Indians in order to steal their corn but the Pilgrims denounced the idea as, “being against the law of God and Nature…and also of the propagation of the knowledge and Law of God.”[15]

The annoyance proved too great for some of the native tribes who decided to not only destroy the Wessagusset Colony but also the Pilgrims at Plymouth for no other reason than the fact that they looked the same as the others. However, several allied Indian tribes sent messengers or appeared personally to the Pilgrims warning of “their secret and villainous purposes.”[16] Most significantly, their oldest and dearest ally among the native tribes, Chief Massasoit, had “discovered the conspiracy of these Indians” and similarly sent information to the Pilgrims of the danger.[17]

On March 23, Governor Bradford presented the evidence of the danger to the Public Court, “having double testimony and many circumstances agreeing with the truth thereof.”[18]It was decided that in order to prevent the murder of all the English settlers in Plymouth and the wider Massachusetts Bay area, Captain Standish would lead a group of men against the natives who were known to be behind the plot and, “take them in such traps as they lay for others,” because, “it is impossible to deal with them upon open defiance.”[19]With this, Standish and his handful of men were off.

Despite the fact that Standish had intended to ambush the natives who were themselves in the process of attempting to launch a surprise attack upon Plymouth, a scout from the native band presented himself to the company and announced that they knew of Standish’s mission, “but we fear him not, neither will we shun him, but let him begin when he dare, he shall not take us at unawares.”[20]More natives then arrived and began sharpening their weapons and making warlike speeches including one named Wituwamat who, “bragged of the excellency of his knife” and how he had used it to kill “both French and English.”[21]Also there was one of the leading Sachems of chiefs of the conspiracy, Pecksuot, who was considerably bigger than Standish. The chieftain looked at the shorter man and declared that Standish, “was but a little man.”[22] To this Standish replied, “though I be no Sachem, yet I am a man of great strength and courage.”[23]

The next day was to decide the contest and the fate of Plymouth hung in the balance. Standish, along with three other colonists, met with Chief Pecksuot, the warrior Wituwamat, and two other Indians. There could have been no misunderstanding that these men were gathering to fight. When hostilities broke out, Standish charged the large chieftain, grabbed Pecksuot’s own knife, and “with much struggling killed him therewith.”[24] The other Indians, including one named Hobbamocke, “stood all this time as a spectator and meddled not.”[25]After the colonists emerged victorious in this pitched battle of hand-to-hand combat, Hobbamocke made the following speech announcing Pilgrim victory:

Yesterday Pecksuot bragging of his own strength and stature, said, though you were a great Captain yet you were but a little man; but today I see you are big enough to lay him on the ground.[26]

After this there were a handful of additional skirmishes between colonial and native forces after which Standish and his troops sailed back to Plymouth. Upon their arrival, a severed head was posted outside of the town as a stark warning against any other plots and a prisoner confessed the full scope of the planned genocide of Plymouth colony.[27] This Indian was released and sent back to his tribe as an exchange for three colonists who had been forced to make canoes which would have been used in the attack on Plymouth but they had already been executed.[28]

When news of the conflict with the natives reached England, however, not all were satisfied with how the situation had been handled. Most notably, the Pilgrim’s old pastor John Robinson, who still led the church in Leiden, remonstrated against this course of action saying:

Concerning the killing of those poor Indians, of which we heard at first by report, and since by more certain relation, oh! How happy a thing had it been if you had converted some before you had killed any; besides, where blood is once begun to be shed, it is seldom stanched of long time after. You will say they deserved it. I grant it; but upon what provocations and invitments by those heathenish Christians? [Referring to Weston’s group of settlers.].…Upon this occasion let me be bold to exhort you seriously to consider of the disposition of your Captain, whom I love, and am persuaded the Lord in great mercy and for much good hath sent you him, if you use him aright. He is a man humble and meek amongst you, and towards all in ordinary course. But now, if this be merely from an humane spirit, there is cause to fear that by occasion, especially of provocation, there may be wanting that tenderness of life of man (made after God’s image) which is meet. It is also a thing more glorious in men’s eyes, than pleasing in God’s, or convenient for Christians, to be a terror to poor barbarous people; and indeed I am afraid least, by these occasions, others should be drawn to affect a kind of rushing course in the world.[29]

And while certainly it is commendable to desire that the hostile natives had chosen to convert to Christianity prior to such a conflict, it is nevertheless true that such a perspective is much easier to have from across the Atlantic. Edward Winslow, whose report of the events was published the same year that Robinson wrote his letter, laments that such actions were regrettably necessary:

We knew no means to deliver our countrymen and preserve ourselves, than by returning their [the Indians’] cruel purposes upon their own heads, and causing them to fall into the same pit they had digged for others; though it much grieved us to shed the blood of those who good we ever intended and aimed at as a principal in all our proceedings.[30]

Despite the words of Robinson, Captain Standish continued to serve with distinction as one of the primary leaders in Plymouth. He was often called to serve in the civil government, acting as assistant to the governor in many years including, 1633, 1634, 1637, 1638, 1639, 1640, 1641, 1646, 1650, 1651, 1654, 1655, and 1656.[31] Beyond his roles in Plymouth, however, Standish continued to take a leading role in some of the Pilgrim’s more dramatic stories.

For example, Standish was chosen to be sent back to England in 1625 as an, “agent in the behalf of the Plantation in reference unto some particulars yet depending betwixt them and the Adventurers,” which was the company that had sponsored the voyage in the first.[32] When he arrived back in Plymouth the following year after successfully accomplishing his mission, Standish had the sad burden of announcing to the Pilgrims that, “Mr. John Robinson their pastor was dead, which struck them with much sorrow and sadness.…the Lord had appointed him to go a greater journey, at less charge, to better place.”[33]

Then, in 1628, Standish was tasked with arresting a man by the name of Thomas Morton who had founded a colony in the area which was called Merry Mount. Morton was known as the, “Lord of Misrule,” because he, “fell to great licentiousness of life in all profaneness, and…maintained, as it were, a school of atheism.”[34] Besides conducting many pagan rituals and celebrations, Morton also began trading guns to the native tribes in order to fund his extravagant lifestyle and parties.[35] When the company came to arrest him, Morton locked himself away and had an armed guard of his own to resist any attempt. However, being intoxicated, Morton stepped outside, “to make a shot at Captain Standish,” but the Captain rushed forward in that moment, pushed the gun aside, and arrested the belligerent Morton.[36]

It is interesting that in one of Jane Goodwin Austin’s historically flavored literary novels she makes the claim that Thomas Morton held the unique distinction of being the, “possessor of a pocket-clock, the only one…since even Standish did not aspire to such luxury, and was well content to divide his day by the sun and the dial.”[37] However, her books are at best historical fiction and are indeed the source of many of the popular myths which people often confuse to be fact about the Pilgrims. None of the original sources which make mention of Standish’s arrest of Morton include any remarks about either person having or not having a pocket watch.

Indeed, the provenance strongly suggests much rather that this pocket watch was indeed owned by Myles Standish and potentially even came over with him on the Mayflower. The documentary provenance stretches across the generations of the descendants of famous leaders who came across in the hull of the Mayflower.[38]When Captain Standish died in 1656, the watch was likely passed to his oldest surviving son, Alexander Standish (1626-1702), who then gave it to his daughter Sarah Standish who married Benjamin Soule (1670-1729), the grandson of Mayflower passenger George Soule (1601-1679). The couple then bequeathed this watch to their son Zachariah Soule (1694-1751). Next the watch passed to Zachariah’s son Ephraim Soule (1723-1817), who likewise gave the timepiece to his own son, Corporal Daniel Soule (1757-1838) who fought in the Revolutionary War.

The next owner of the Standish Watch was Josiah Soule (1794-1872) who, following tradition, gave the watch to his son named Josiah Soule, Jr. (1819-1880). Next in line was Lt. Commander Henry Bishop Soule (1866-1935) who just so happened to not only be the great-great-great-great-great-great grandson of Captain Myles Standish but also of John and Priscilla Alden, and George Soule who all traveled to America together on the Mayflower. When Henry died the watch became the de facto possession of his wife who had indented to bequeath it to the National Museum of the Smithsonian Institute after her death in 1944.[39] However, on the authority of Lt. Commander Soule’s will, the timepiece instead was inherited by his niece Dianne Haler who lived in Ohio. The paper explained that, “The English-manufactured timepiece has a porcelain face with brass back and is slightly thicker than present-day watches.”[40]

The watch occasionally appears in the historical record at various exhibitions where it was proudly displayed. At the 1983 world’s fair in Chicago the Standish Watch held a place of prominence among several historical watches on display including one from George Washington’s family and old devices from the early days of the US Navy.[41] One reported noted specifically that it was indeed the watch Standish “brought over on the Mayflower.”[42] Another report went into more detail, describing the piece as, “a copper watch worn by Miles Standish during the historical trip of the Mayflower in 1620.”[43]

Captain Standish lived a long life and was extremely valuable to the Pilgrims, especially during those early years when danger confronted them on every side. Throughout the rest of his life he continued to figure prominently as a leader in Plymouth in business, military, and political affairs. Towards the end of his life, an elderly Indian chieftain who had been friends with Standish for many years, even came and settled on the Captain’s farm.[44] In 1656, after being chosen yet again to serve as one of the Assistants in Government under Governor William Bradford, Captain Standish, “fell asleep in the Lord.”[45]He had suffered, “a deep share of their first difficulties and was always very faithful to their interest.”[46]When executors of his will went through his estate they documented the interesting fact that, “the number of muskets just equaling that of the Bibles.”[47]Unfortunately, many of his relics were lost to history when his house burned down in the 1660s, his pocket watch, however, has stood the test of time and holds a unique place in the American Journey Experience collection.

[1] William Bartlett, The Pilgrim Fathers; of, Founders of New England in the Reign of James the First (London: T. Nelson and Sons, 1863), 41. Here.

[2] Nathaniel Morton, New-England’s Memoriall: or, A Brief Relation of the Most Memorable and Remarkable Passages of the Providence of God, Manifested to the Planters of New-England in America (Boston: John Usher, 1669), 143. Here.

[3] William Bartlett, The Pilgrim Fathers; of, Founders of New England in the Reign of James the First (London: T. Nelson and Sons, 1863), 61-62. Here.

[4] William Bartlett, The Pilgrim Fathers; of, Founders of New England in the Reign of James the First (London: T. Nelson and Sons, 1863), 42. Here.

[5] William Bradford, History of Plymouth Plantation, 1620-1647 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1912), 1.196. Here.

[6] William Bradford, History of Plymouth Plantation, 1620-1647 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1912), 1.162. Here.

[7] William Bradford, History of Plymouth Plantation, 1620-1647 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1912), 1.196. Here.

[8] William Bradford, History of Plymouth Plantation, 1620-1647 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1912), 1.196. Here.

[9] For examples see, William Bradford, History of Plymouth Plantation, 1620-1647 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1912), 1.281, 294. Here.

[10] Edward Winslow, Good Newes from New England: or A True Relation of Things Very Remarkable at the Planation of Plimouth in New-England (London: William Bladen and John Bellamie, 1624), 24.

[11] Nathaniel Morton, New-England’s Memoriall: or, A Brief Relation of the Most Memorable and Remarkable Passages of the Providence of God, Manifested to the Planters of New-England in America (Boston: John Usher, 1669), 42. Here.

[12] Nathaniel Morton, New-England’s Memoriall: or, A Brief Relation of the Most Memorable and Remarkable Passages of the Providence of God, Manifested to the Planters of New-England in America (Boston: John Usher, 1669), 42. Here.

[13] William Bradford, History of Plymouth Plantation, 1620-1647 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1912), 1.276. Here.

[14] William Bradford, History of Plymouth Plantation, 1620-1647 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1912), 1.288-290. Here.

[15] Edward Winslow, Good Newes from New England: or A True Relation of Things Very Remarkable at the Planation of Plimouth in New-England (London: William Bladen and John Bellamie, 1624), 35-36, here.

[16] Edward Winslow, Good Newes from New England: or A True Relation of Things Very Remarkable at the Planation of Plimouth in New-England (London: William Bladen and John Bellamie, 1624), 34, 37, here.

[17] Nathaniel Morton, New-England’s Memoriall: or, A Brief Relation of the Most Memorable and Remarkable Passages of the Providence of God, Manifested to the Planters of New-England in America (Boston: John Usher, 1669), 42. Here.

[18] Edward Winslow, Good Newes from New England: or A True Relation of Things Very Remarkable at the Planation of Plimouth in New-England (London: William Bladen and John Bellamie, 1624), 37. Here.

[19] Edward Winslow, Good Newes from New England: or A True Relation of Things Very Remarkable at the Planation of Plimouth in New-England (London: William Bladen and John Bellamie, 1624), 38. Here.

[20] Edward Winslow, Good Newes from New England: or A True Relation of Things Very Remarkable at the Planation of Plimouth in New-England (London: William Bladen and John Bellamie, 1624), 42. Here.

[21] Edward Winslow, Good Newes from New England: or A True Relation of Things Very Remarkable at the Planation of Plimouth in New-England (London: William Bladen and John Bellamie, 1624), 42. Here.

[22] Edward Winslow, Good Newes from New England: or A True Relation of Things Very Remarkable at the Planation of Plimouth in New-England (London: William Bladen and John Bellamie, 1624), 42. Here.

[23] Edward Winslow, Good Newes from New England: or A True Relation of Things Very Remarkable at the Planation of Plimouth in New-England (London: William Bladen and John Bellamie, 1624), 42. Here.

[24] Edward Winslow, Good Newes from New England: or A True Relation of Things Very Remarkable at the Planation of Plimouth in New-England (London: William Bladen and John Bellamie, 1624), 42. Here.

[25] Edward Winslow, Good Newes from New England: or A True Relation of Things Very Remarkable at the Planation of Plimouth in New-England (London: William Bladen and John Bellamie, 1624), 43. Here.

[26] Edward Winslow, Good Newes from New England: or A True Relation of Things Very Remarkable at the Planation of Plimouth in New-England (London: William Bladen and John Bellamie, 1624), 43. Here.

[27] Edward Winslow, Good Newes from New England: or A True Relation of Things Very Remarkable at the Planation of Plimouth in New-England (London: William Bladen and John Bellamie, 1624), 45. Here.

[28] Edward Winslow, Good Newes from New England: or A True Relation of Things Very Remarkable at the Planation of Plimouth in New-England (London: William Bladen and John Bellamie, 1624), 45. Here.

[29] John Robinson quoted in, William Bradford, History of Plymouth Plantation, 1620-1647 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1912), 1.367-369. Here.

[30] Edward Winslow, Good Newes from New England: or A True Relation of Things Very Remarkable at the Planation of Plimouth in New-England (London: William Bladen and John Bellamie, 1624), 37-38. Here.

[31] Nathaniel Morton, New-England’s Memoriall: or, A Brief Relation of the Most Memorable and Remarkable Passages of the Providence of God, Manifested to the Planters of New-England in America (Boston: John Usher, 1669), 89, 92, 106, 111, 112, 114, 123, 133, 134, 141, 142, 143.

[32] Nathaniel Morton, New-England’s Memoriall: or, A Brief Relation of the Most Memorable and Remarkable Passages of the Providence of God, Manifested to the Planters of New-England in America (Boston: John Usher, 1669), 62, Here.

[33] Nathaniel Morton, New-England’s Memoriall: or, A Brief Relation of the Most Memorable and Remarkable Passages of the Providence of God, Manifested to the Planters of New-England in America (Boston: John Usher, 1669), 63, here.

[34] Nathaniel Morton, New-England’s Memoriall: or, A Brief Relation of the Most Memorable and Remarkable Passages of the Providence of God, Manifested to the Planters of New-England in America (Boston: John Usher, 1669), 69. Here.

[35] Nathaniel Morton, New-England’s Memoriall: or, A Brief Relation of the Most Memorable and Remarkable Passages of the Providence of God, Manifested to the Planters of New-England in America (Boston: John Usher, 1669), 70-71. Here.

[36] Nathaniel Morton, New-England’s Memoriall: or, A Brief Relation of the Most Memorable and Remarkable Passages of the Providence of God, Manifested to the Planters of New-England in America (Boston: John Usher, 1669), 72. Here.

[37] Jane Goodwin Austin, Betty Alden: The First-Born Daughter of the Pilgrims (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1891), 83. Here.

[38] For an image of the original provenance documentation see, “Magnificent Pocket Watch Strongly Attributed to Captain Myles Standish, Lot 174,” Worth Point (accessed February 3, 2022): here.

[39] “Mrs. Henry B. Soule, Commander’s Widow, Dies in Navy Hospital,” Washington Evening Star (November 5, 1944), A-16. Here.

[40] “Miles Standish Watch Cherished in Ohio,” Yuma Sun (September 25, 1952), 15. Here.

[41] Alexis McCrossen, Making Modern Times: A History of Clocks, Watches, and Other Timekeepers in American Life (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2013), 145. Here.

[42] Gertie McClintock, “World Fair Sketches,” Idaho Semi-Weekly World (September 29, 1893), 1. Here.

[43] “Relics That Are Priceless,” Stanford Semi-Weekly Interior Journal (October 13, 1893), 4. Here.

[44] John Goodwin, The Pilgrim Republic: An Historical Review of the Colony of New Plymouth (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1920), 450. Here.

[45] Nathaniel Morton, New-England’s Memoriall: or, A Brief Relation of the Most Memorable and Remarkable Passages of the Providence of God, Manifested to the Planters of New-England in America (Boston: John Usher, 1669), 144. Here.

[46] Nathaniel Morton, New-England’s Memoriall: or, A Brief Relation of the Most Memorable and Remarkable Passages of the Providence of God, Manifested to the Planters of New-England in America (Boston: John Usher, 1669), 143-144. Here.

[47] John Goodwin, The Pilgrim Republic: An Historical Review of the Colony of New Plymouth (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1920), 450. Here.