In the late 1500s, the state Church of England dominated the country. The King or Queen of England was its head, and every citizen born within a certain radius of a Church of England was automatically made a member and taxed accordingly. This all started to change however, when the Bible was printed in English. As the common people began reading the word of God for themselves, they noticed shortcomings in the church.

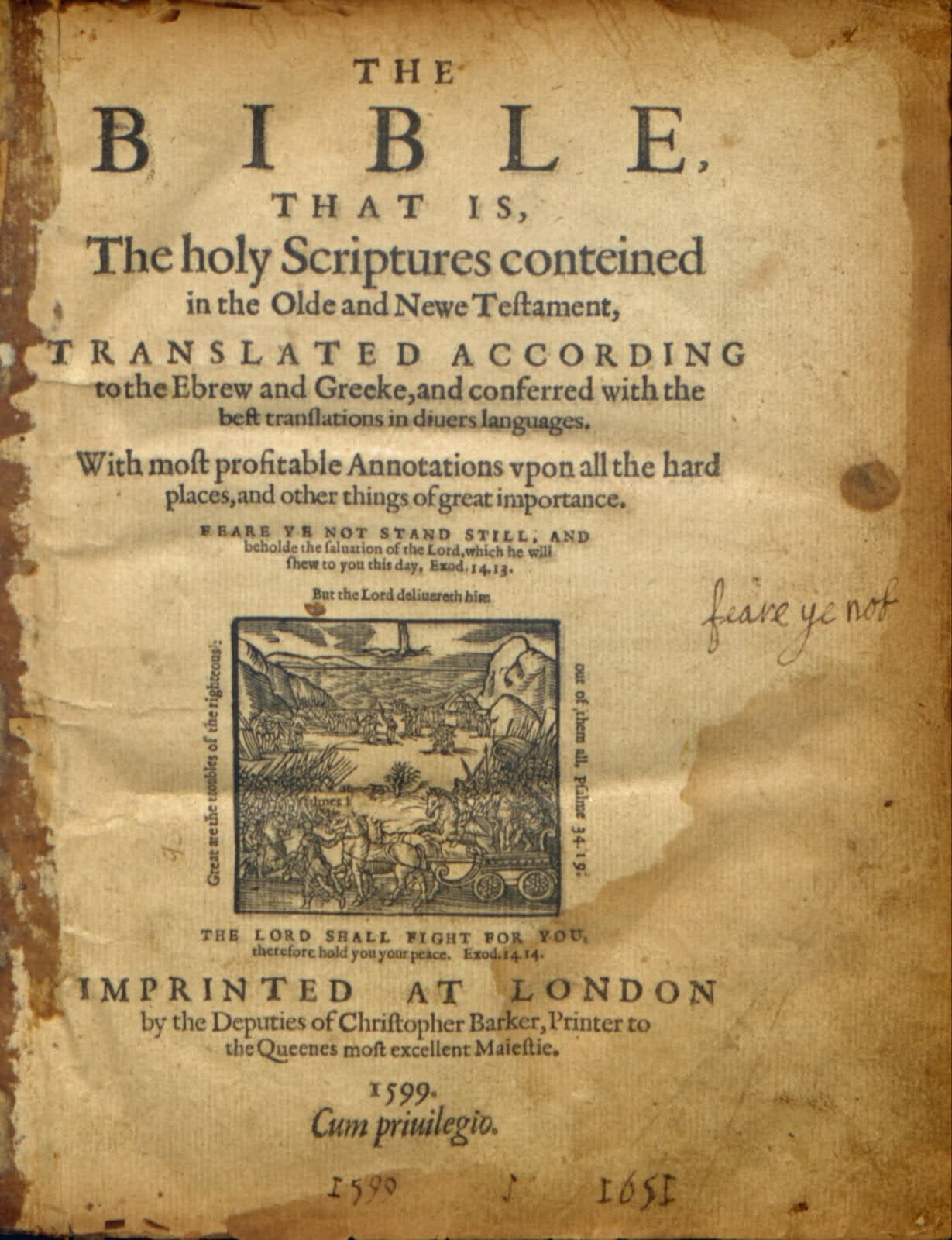

An instrumental translation in this awakening was the Geneva Bible. Between 1560 and 1644, over 180 editions of it were printed. The American Journey Experience is proud to own a copy of this book. One of its most influential features was its margin notes, which openly criticized the monarchy and its relationship with the church. (Geneva bible image) This in part sparked dissatisfaction towards church, and many English began worshiping in their own homes. The crown saw this as tantamount to treason. From 1560-1700, Parliament passed several laws officially criminalizing worship in any form other than attendance to the government’s church in England and Scotland. Despite the danger entailed, citizens of England and Scotland continued to meet in secret and became known as the “Separatists”.

(First Page of the Geneva Bible, printed in 1599)

One small group of Separatists in Nottinghamshire, England met in Scrooby Manor under the direction of Reverend Richard Clyfton. They met by candlelight to study the Bible and worship. Their number included William Bradford, who joined the secret congregation at only twelve years old. Only two years later, his guardians (Bradford’s aunt and uncle) forbid him from attending the separatist group, threatening him with disownment and expulsion from their home should he disobey. In response, Bradford voluntarily left their residence, choosing his freedom of worship over the comforts of home. It was not long until the entire body of Separatists would have to face this same dilemma. In 1607, the Scrooby Manor meetings were discovered by local leaders of the Church of England, and the consequences were disastrous. To quote Bradford, the Separatists “were hunted and persecuted on every side, so as their former afflictions were but as flea-bitings in comparison of these which now came upon them. For some were taken and clapt up in prison, others had their houses beset and watched night and day, and hardly escaped their hands; and the most were fated to flee and leave their houses and habitations, and the means of their livelihood”1

Suffering oppression to the point of being quite literally hunted down and murdered for their religious beliefs, the surviving Separatists chose to flee the country. Amsterdam was their destination of choice, being known for its religious tolerance, but this was easier decided than carried out. The Separatists suffered betrayal, loss of property, and imprisonment along the way. When they did arrive in Holland, they found prosperity and religious freedom. The Pilgrims remained in Holland (specifically Amsterdam and Leiden) for between 11 and 12 years 2, but ultimately longed for a place where they could raise their children free from worldly distractions, receive a greater reward for their work, and participate in spreading the word of God. According to William Bradford, “a great hope and inward zeal they had of laying some good foundation, or at least to make some way thereunto, for the propagating and advancing the gospel of the kingdom of Christ in those remote parts of the world yea, though they should be but even as stepping-stones unto others for the performing of so great a work.”3

At great peril, some Pilgrims returned to England to negotiate terms with members of The Virginia Company, one of the earliest and most famous English colonial ventures. The Virginia Company was eager to take the Pilgrims on, and headed up negotiations with the hostile King and Archbishop. While they were not able to reach a guarantee of the Pilgrims’ rights, the King did agree to “not molest them, provided they carried themselves peaceably”4, which the Pilgrims ultimately deemed sufficient.

The Pilgrims were originally granted two ships for their passage, but once again sabotage befell them. One ship was deemed unfit for travel, and a great number of the Pilgrims had to part ways, returning to Holland, never reaching the shores of the New World. The crew of the second ship (the Mayflower) delayed the departure by a full year in an attempt to escape crossing the sea at all 5. When the Mayflower finally set out it was blown badly off course. Instead of achieving its original destination of New York it anchored in Cape Cod, months late. Here, the Pilgrims drew up and signed the Mayflower Compact, a governing document of sorts that declared the Pilgrims purpose in settling a new colony and the principles by which they agreed with one another to live by.

“In the name of God, Amen. We whose names are underwritten, the loyal Subjects of our dread sovereign Lord King James, by the grace of God of Great Britain, France, and Ireland King, Defender of the Faith, &c. Having undertaken for the glory of God, and advancement of the Christian Faith, and honor of our King And Country, a Voyage to plant the first Colony in the Northern parts of Virginia; do by these presents

solemnly and mutually, in the presence of God and one another, covenant, and combine ourselves together into a civil body politick, for our better ordering and preservation and furtherance of the ends aforesaid; and by virtue hereof do enact, constitute, and frame such just and equal Laws, Ordinances, acts, constitutions, and offices from time to time, as shall be thought most meet and convenient for the general good of the Colony; unto which we promise all due submission and obedience. In witness whereof we have hereunto subscribed our names at Cape Cod the 11. of November, in the year of the reign of our sovereign Lord King James, of England, France, and Ireland, the eighteenth, and of Scotland the fifty-fourth, Anno Domini 1620” 6

The seeds of a nation based on the equality and liberty given to man by God were already being sown.

In December of 1620, the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth rock, but with no pre-existing structures or provisions waiting for them the winter was incredibly difficult. The Pilgrims were wracked with sickness and starvation, reducing their number by half. As spring approached, the survivors had no certainty they would live through the coming year. Providentially, this is when an unexpected Native American ally came into their lives. His name was Squanto.

Squanto was a member of the Patuxet tribe, which had once inhabited the land where the Pilgrim settlers built their settlements. Squanto was captured by a cruel sea captain and sold into slavery in Europe. He was eventually freed from his enslaved condition by Spanish monks, who taught him English and helped him convert to Christianity. Under the care of monks in Spain, Squanto eventually found a way to return to America on a trading vessel. Upon returning to his home land he found the entirety of his tribe dead, killed by an unknown disease (likely Smallpox). Without family or friends, yet miraculously saved from whatever ailment took his people, Squanto decided to live with the nearby Wamponoag tribe. The spring after the Pilgrims landed, they encountered members of the Wampanoag tribe who introduced them to Squanto. Observing the Pilgrim’s dire state, Squanto willingly became their mentor, teaching them how to cultivate the land of his inheritance. He taught them how to grow corn, the best places to fish, and helped them forge long-lasting and mutually beneficial treaties with surrounding tribes7. The Pilgrims were grateful for Squanto and his invaluable service. Without his aid, they likely would have died of starvation the following winter and completely failed as a settlement. William Bradford glowingly wrote that “Squanto…was a special instrument sent of God for their good beyond their expectation…and never left them till he died”8.

Squanto’s assistance led to the Pilgrim’s prosperity. By the following fall they had enough food stored that they believed they would all be able to make it through the winter. This was a true miracle, and one they were surely overwhelmingly grateful for. It meant the difference between life and death. To celebrate this success, the Pilgrims invited the Wampanoag tribe for three days of feasting. 90 Braves attended the festivities (outnumbering the surviving Pilgrims nearly 2 to 1) and contributed 5 deer to the meals. The Pilgrims provided fowl and other foods, and arranged various competitive games for their entertainment, including marksmanship. These were the events of the first Thanksgiving 9.

Thanks to the Pilgrim and Wampanoag leadership – Squanto, Governor John Carver and the Plymouth governors who followed him, and Wampanoag Chief Massasoit – and their desire for a peaceful and mutually beneficial alliance, the Pilgrims enjoyed a positive relationship with their Native American neighbors. In fact, a treaty signed by the Pilgrim and Wompanoag leaders in March of 1621 would go on to last decades, only being broken over 50 years later by Chief Massasoit’s son Metacom (also known as King Phillip) when he declared war on English colonists in 1675. This treaty produced many benefits for both sides. The Wompanoag warned the colony of coming attacks from other tribes, Governor Edward Winslow saved Chief Massasoit’s life when threatened by illness, and both sides benefited from trade 10.

The Pilgrims were far from being out of the woods. As new colonists joined them in the “New World” there would be continued struggles of food shortages, debt, and disease, but with the first Thanksgiving the Pilgrims proved a point. With adequate work, time, and the help of God, their colony could survive, and that they did. Many Pilgrims lived to enjoy, at least in some small part, what they had dreamed of and sacrificed for: A place to raise their children, earn a just reward for their work, and freely live by and share the word of God.

1. Bradford, William. Original Narratives of Early American History, Reproduced under the Auspices of the American Historical Association, Bradford’s History of Plymouth Plantation 1606—1646. Edited by J. Franklin Jameson and William T. Davis, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1908 (p.32).

2. Bradford, William Bradford’s History of Plymouth Plantation (p.44).

3. Bradford, William Bradford’s History of Plymouth Plantation (p.46).

4. Bradford, William Bradford’s History of Plymouth Plantation (p.51).

5. Bradford, William Bradford’s History of Plymouth Plantation (pp.88-89).

6. “The Mayflower Compact.” Www.Gilderlehrman.Org, The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, 2013, www.gilderlehrman.org/sites/default/files/inline-pdfs/The%20Mayflower%20Compact.pdf.

7. Adams, Charles Francis. Three Episodes of Massachusetts History: The Settlement of Boston Bay; the Antinomian Controversy; a Study of Church and Town Government . Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1892. (pp. 23-44).

8. Bradford, William Bradford’s History of Plymouth Plantation (p.111).

9. Bradford, William, et al. Mourt’s Relation; or, Journal of the Plantation at Plymouth, with an Introduction and Notes by Henry Martyn Dexter. J.K. Wiggin, 1865. (pp. 133-134). https://www.worldhistory.org#organization, 2 Dec. 2020, www.worldhistory.org/Pilgrim-Wampanoag_Peace_Treaty/.

10. Mark, Joshua J. “Pilgrim-Wampanoag Peace Treaty.” World History Encyclopedia,