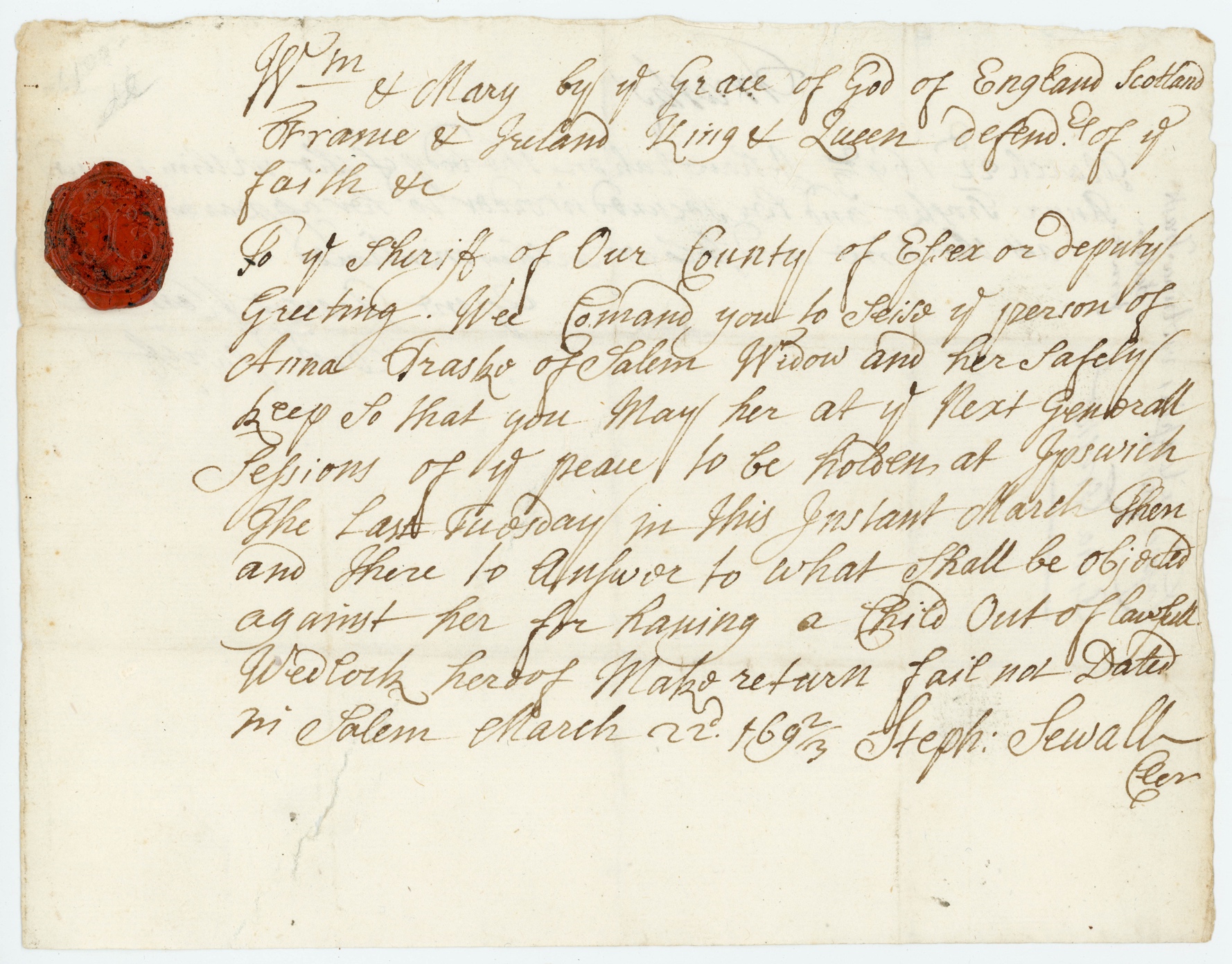

Warrant for the arrest of an accused witch

Six years before his coronation to the throne of England, King James wrote and published Demonology, a dissertation on demons, necromancy, divination and witchcraft.1 The royal circles of England praised the book and made it a common subject of conversation, especially among those inclined to seek Jame’s approval. When James came to power the book was reprinted and widely circulated.2 Less than a year into his reign, the English parliament passed severe statutes against witchcraft in an attempt to win his favor. The “Act against Conjuration, Witchcraft and dealing with evil and wicked Spirits” specifically made witchcraft a crime punishable by death.3 This act and the general hysteria encouraged by King James and Demonology cost thousands of lives during his reign and beyond. According to one study, across Europe from 1300-1850 over 43,000 people were tried of witchcraft, with over 16,000 of those tried being executed.4 Astonishing as these numbers may be, they are on the low side of scholarly estimation. It is more commonly held that over 110,000 trials took place with a much higher, but uncertain number convicted and executed.5

When the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth in 1620 they brought English law with them, including the death penalty for those practicing witchcraft.6 They did not however, bring King James’ religious ideals or the witch hunting hysteria so prevalent in England and Scotland. A major part of the Pilgrims motivation in moving to America was to free themselves from the crown’s involvement in the church. It wasn’t until 72 years after the pilgrims’ arrival to America, after nearly all of the original Mayflower passengers had passed away, that the first person was convicted of being a witch in Massachusetts.

In February of 1692, several girls in Salem Massachusetts played a fortune telling game meant to help them predict who their future husbands would be. This game consisted of pouring an egg white into a glass of warm water and observing the shape it formed. The shape was believed to give clues about a future spouse of the player. The participants included Ann Putnam, the 12 year old daughter of Thomas Putnam. The Putnam family were wealthy and had resided in Salem for 4 generations, making the family very influential. While observing the egg white’s shape in the water Ann (or possibly one of the other girls) saw it take the shape of a coffin, which utterly terrified and haunted her. It was not long after this that Ann began suffering from “fits”. These episodes consisted of very unusual behavior such as fevers, strange contortions, and unexplained bites and bruises.7 Several other young women followed suit, including Mercy Lewis. Mercy Lewis lived in the Putnam’s home as a servant. When she was 14 both of her parents were killed by Wabanaki Indians, leaving her no way to provide for herself other than servitude. She was 17 years old when she began suffering from fits similar to Ann’s.8

When a physician was called upon to discover the cause of the Putnam household’s fits as well as the other girls, he was unable to find a physical cause and gave his opinion that they were bewitched. The girls quickly accepted this idea. It was only a few days before accusations began to fly. 7 Over the course of the next 15 months these girls, as well as others claiming to suffer various ailments or misfortune at the hands of the devil, accused over 200 men and women of witchcraft. Ann Putman personally testified against 62 of these accused. Since Ann was too young to file official complaints, her father Thomas did so for her. Thomas himself testified against 43 accused witches. Many modern historians consider Thomas Putman a major ringleader in the trials, using the hysteria as a means of achieving revenge on his family’s generational enemies.9

Salem Massachusetts’ court system was far from the standards of today, especially when it came to what kind of evidence was accepted for conviction. Evidence used in these trials included “the devil’s mark” (a strange mole or birthmark) on the accused person’s body, testimonies of spectral visits or curses brought on by the accused, family relationship or friendship with a previously convicted witch, reports of talking to animals, and sudden fits of pain or rage caused by their touch. It is important to note that the vast majority of this evidence was spectral evidence, or hearsay. Frequently, as a witch was being tried the accusers would attend, and any time the “witch” would look at them they would begin crying, screaming, or flailing about, reporting pain. It was not uncommon that confessions would be forced out of the accused via harassment.10

As witch-hunting spread through Salem, many local leaders in church and education took notice. Thomas Brattle, treasurer and unofficial professor of astronomy and mathematics at Harvard (a then Christian school) and co-founder of Brattle Street Church was a spectator at multiple witch trials. He was greatly disturbed by the forms of evidence used, and the arbitrary manner in which warrants were issued. On October 8th of 1692, he wrote a letter in which he gave a full account of what he witnessed at the witch trials and vehemently denounced them proclaiming

“I am afraid that ages will not wear off that reproach and those stains which these (trials) will leave behind them upon our land. I pray God pity us, Humble us, Forgive us, and appear mercifully for us in this our mount of distress”.11

Thomas Maule, an influential Quaker of the time, was also dissatisfied with the trials. Thomas and his wife Naomi both believed in witches, and Naomi testified against Bridget Bishop, the first woman to be executed for witchcraft in Salem. With time, Thomas became disillusioned with the trials and aware of the innocent lives the trials took. He published a pamphlet titled “Truth Held Forth and Maintained” in which he condemned the trials and proclaimed his belief that the judges involved would be punished by God. Of the trials, Maule’s pamphlet reads

“It were better that one hundred Witches should live, than that one person be put to death for a Witch, which is not a Witch”.12

Reverend John Wise, an Ipswich Massachusetts minister likewise disapproved of the trials. Wise, along with 35 others, signed an appeal to the court on behalf of John and Elisabeth Proctor, who had spoken out against the witch trials early on. They were accused of witchcraft by Ann Putnam and Mercy Lewis among others. Out of the 35 signers, Wise was the only one brave enough to personally confront the magistrates involved, even though actions of support towards an accused witch could have led to his own accusation.13 Regardless of Wise’s intercession, John Proctor was convicted and hanged. His wife Elizabeth was also convicted, but her execution was postponed due to her pregnancy.14 She survived the witch trials and was freed at their close. Though John Proctor was executed, John Wise continued to befriend and give what assistance he could to the accused. Having suffered an unjust trial himself at the hands of the English crown, John Wise was all too familiar with the accused witches’ suffering, and was likely very influential in the witch trials’ end.

On October 29th 1692, Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Sir Williams Phips dismissed the Court of Oyer and Termer, beginning the end of the Salem witch trials.15 The 52 individuals who remained in prison were tried under a new court that did not permit spectral evidence, and most were either dismissed due to a lack of evidence or found not guilty. Those who were found guilty were pardoned by Phips and released in May of 1693.16 Governor Phips likely ended the trials due to pressure from various political and church leaders who were outraged at the use of spectral evidence, and possibly the accusation of Phip’s own wife.

The Salem witch trials lasted approximately 15 months, from February 1692 to May 1693. The trials resulted in the death of 24 individuals, 19 of which were hanged, 1 of which was tortured to death when he refused to enter a plea, and 4 of which died in prison.16 These harrowing events played on Ann Putnam and others’ consciences. In 1706, 14 years after the trials, Ann Putnam made a public apology for her actions

“I desire to be humbled before God for that sad and humbling providence that befell my father’s family in the year about ’92; that I, then being in my childhood, should, by such a providence of God, be made an instrument for the accusing of several persons of a grievous crime, whereby their lives were taken away from them, whom now I have just grounds and good reason to believe they were innocent persons; and that it was a great delusion of Satan that deceived me in that sad time, whereby I justly fear I have been instrumental, with others, though ignorantly and unwittingly, to bring upon myself and this land the guilt of innocent blood; though what was said or done by me against any person I can truly and uprightly say, before God and man, I did it not out of any anger, malice, or ill-will to any person, for I had no such thing against one of them; but what I did was ignorantly, being deluded by Satan… I desire to lie in the dust, and to be humbled for it, in that I was a cause, with others, of so sad a calamity to them and their families; for which cause I desire to lie in the dust, and earnestly beg forgiveness of God, and from all those unto whom I have given just cause of sorrow and offence, whose relations were taken away or accused”. 17

Samuel Sewall, a major judge in the Salem witch trials also greatly regretted his part, issuing the following public apology.

“Samuel Sewall, sensible of the reiterated strokes of God upon himself and family; and being sensible, that as to the guilt contracted upon the opening of the late commission of Oyer and Terminer at Salem (to which the order for this day relates) he is, upon many accounts, more concerned than any that he knows of, desires to take the blame and shame of it, asking pardon of men, and especially desiring prayers that God, who has an unlimited authority, would pardon that sin and all other his sins, personal and relative; and according to his infinite benignity, and sovereignty, not visit the sin of him, or of any other, upon himself or any of his, nor upon the land.” 18

Pine shilling thought to be used to ward off witches

Works Cited

1. King James I. Dæmonologie in Forme of a Dialogue (1597). E. P. Dutton & Company, 1924.

2. “Daemonologie, in Forme of a Dialogue.” Encyclopedia Virginia, 11 Feb. 2021.

3. “An Act against Witchcraft.” The National Archives, The National Archives, 10 Feb. 2023.

4. Leeson, Peter T, and Jacob W Russ. “WITCH TRIALS.” The Economic Journal, 1 Aug. 2018, p. 2078.

5. Levack, Brian P. The Witch-Hunt in Early Modern Europe. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2016.

6. Whitmore, William H. A Bibliographical Sketch of the Laws of the Massachusetts Colony from 1630 to 1686, Rockwell and Churchill City Printers, Boston , Massachusetts, 1890, p. 55.

7. Hale, John, and John Higginson. A Modest Enquiry into the Nature of Witchcraft and How Persons Guilty of That Crime May Be Convicted: And the Means Used for Their Discovery Discussed, Both Negatively and Affimatively, According to Scripture and Experience. Printed and Sold by Kneeland and Adams, next to the Treasurer’s Office, in Milk-Street, 1771 p. 24, 133.

8. Brooks, Rebecca Beatrice. “Mercy Lewis: Orphaned Afflicted Girl.” History of Massachusetts Blog, 21 Jan. 2014.

9. Brooks, Rebecca Beatrice. “Thomas Putnam: Ringleader of the Salem Witch Hunt?” History of Massachusetts Blog, 24 July 2022.

10. Mather, Cotton. The Wonders of the Invisible World by Cotton Mather. Printed First at Boston in New-England, and Reprinted at London for John Dunton, 1693.

11. Brattle, Thomas. “Letter of Thomas Brattle, F. R. S.,.” Received by Unknown Minister, 8 Oct. 1692.

12. Maule, Thomas. Truth Held Forth and Maintained: According to the Testimony of the Holy Prophets, Christ and His Apostles … 1695 p. 185.

13. Waters, Thomas Franklin. Publications of the Ipswich Historical Society. The Society, 1918, p. 18-19.

14. Brooks, Rebecca Beatrice. “The Witchcraft Trial of Elizabeth Proctor.” History of Massachusetts Blog, 11 Mar. 2023.

15. Sewall, Samuel. Diary of Samuel Sewall. Vol. 1, Massachusetts Historical Society, 1878, p. 368.

16. Brooks, Rebecca Beatrice. “History of the Salem Witch Trials.” History of Massachusetts Blog, 1 Nov. 2023.

17. Ann Putnam’s Confession (1706), University of Oregon, Accessed 30 Oct. 2024.

18. Sewall, Samuel. “The Judge’s Confession.” Original Sources – The Judge’s Confession, Accessed 30 Oct. 2024.