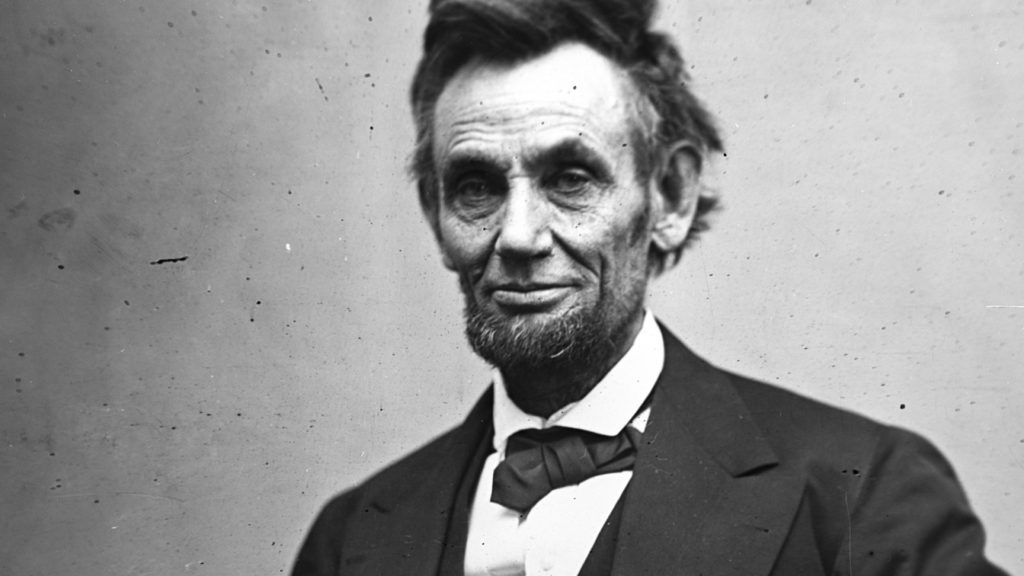

Throughout the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln, burdened with the responsibility of leading a nation at war with itself, would often retreat to the theatre to relax and allow his mind to be absorbed by a play rather than the latest developments of the war. Leonard Grover, manager of Grover’s Theatre in Washington, D.C. wrote the following in his article Lincoln’s Interest in the Theatre:

No President and few men ever went through so trying a personal ordeal as did Mr. Lincoln during the Civil War. Scarce a soldier gained a furlough who did not try to see him, nor a man with a petty wish or grievance who did not seek his personal aid. With a nature most gracious, genial, and kind, it was almost impossible for him to stay them from his presence. To gain relief from the many importunates, he often sought the theater for rest and relaxation. During the four years of his administration, he visited my theater probably more than a hundred times.1

Grover continued:

Lincoln’s various biographers with singular unanimity have refrained from alluding to that which was his chief diversion. One of them says “Rulers of men must occasionally appear among the people: and it was more for this reason than for personal entertainment that Mr. Lincoln, with his wife and a few attendants, visited Ford’s Theatre.” The truth is that there was not the slightest atom of hypocrisy about Mr. Lincoln. He visited the theater as he listed, to be entertained, and for relaxation.2

One such play that Lincoln attended at Grover’s Theatre was Richard III on April 11, 1863, which happened to be the Washington debut of actor John Wilkes Booth, as recorded by Alexander Hunter in his record of the theatre:

On Saturday April 11, 1863, the announcement is made that the distinguished young actor, John Wilkes Booth will make his first appearance in Washington as “King Richard the III.” A very large and fashionable audience greeted him, and, a singular coincidence, President Lincoln and Senator Oliver P. Morton occupied a private box.3

Some speculate that Lincoln saw Booth perform on many occasions, and its possible that Lincoln saw him even more times than are recorded; according to Noah Brooks – Lincoln’s friend who often accompanied him on such excursions – they were able to slip into any performance at any time without the knowledge of anyone else, with the audience not even knowing the president was among them. If they were attending on short notice, the Presidential Box was not always readily available, so Lincoln and his party would slip into whatever the manager could find while remaining unobserved by the audience. This would account for many of Lincoln’s theatre visits going unrecorded.4

On November 9, 1863, Lincoln went to Ford’s Theatre to watch a performance of The Marble Heart starring Booth. John Hay, one of Lincoln’s secretaries, recorded in his journal entry for this date, “Spent the evening at the theatre with the President, Mrs. Lincoln, Mrs. Hunter, Cameron and Nicolay. J. Wilkes Booth was doing Marble Heart. Rather tame than otherwise.”5

By all accounts, the production was incredible, with the Washington Chronicle describing it as a “beautiful emotional play.” The president himself was so enamored with Booth’s performance that, as reported by journalist George Alfred “Gath” Townsend, “Lincoln applauded the actor [John Wilkes Booth] and his performance rapturously, and with all that genial heartiness for which Lincoln was distinguished.”6 Lincoln even sent a note backstage inviting him to the White House. According to John Hay’s journal, actor Frank Mordaunt once said:

Lincoln was an admirer… I know that, for he said to me one day that there was a young actor over in Ford’s Theater whom he desired to meet, but that actor had on one pretext or another avoided any invitations to visit the White House. That actor was John Wilkes Booth.7

Of course as a rebel sympathizer and Confederate spy, Booth evaded Lincoln’s invitation. While he never officially provided a reason, Booth is credited with saying that he would rather have the applause of a Negro to that of the President.8

Alternatively, however, John A. Ellsler, Cleveland theatre manager and lifelong friend of Booth recalled:

The frequent engagements he had played in Washington, brought him in contact with most of our notable men, in civil and military service. Their names were all familiar to him, and he would descant on their deeds of valor and service to our cause with knowledge and eloquence; nor was it a rare thing to hear him mention “Uncle Abe” with the greatest reverence and respect. He spoke of his performances being honored by the President, and members of his family and cabinet; how “Uncle Abe” enjoyed his efforts, and how proud he felt of such encouragement. To quote from his own words, “It is most gratifying to see the President, the head of our country, personally recognizing, and by his presence, endorsing the theatre and the profession. I tell you, we owe him honor and respect; God bless him.9

Without full contextual knowledge, its difficult to reconcile these conflicting reports. Perhaps Booth merely praised “Uncle Abe” publicly to keep up appearances. It seems unlikely that he would genuinely respect Lincoln and his support of the theatre considering that after Lincoln’s reelection on November 8, 1864, Booth developed a plan to kidnap the president and exchange him for Confederate prisoners held in Richmond, VA. Booth’s plan went through many different iterations, including one that involved capturing Lincoln while he was watching a play in Ford’s theatre, but ultimately, none of these plans were carried out.

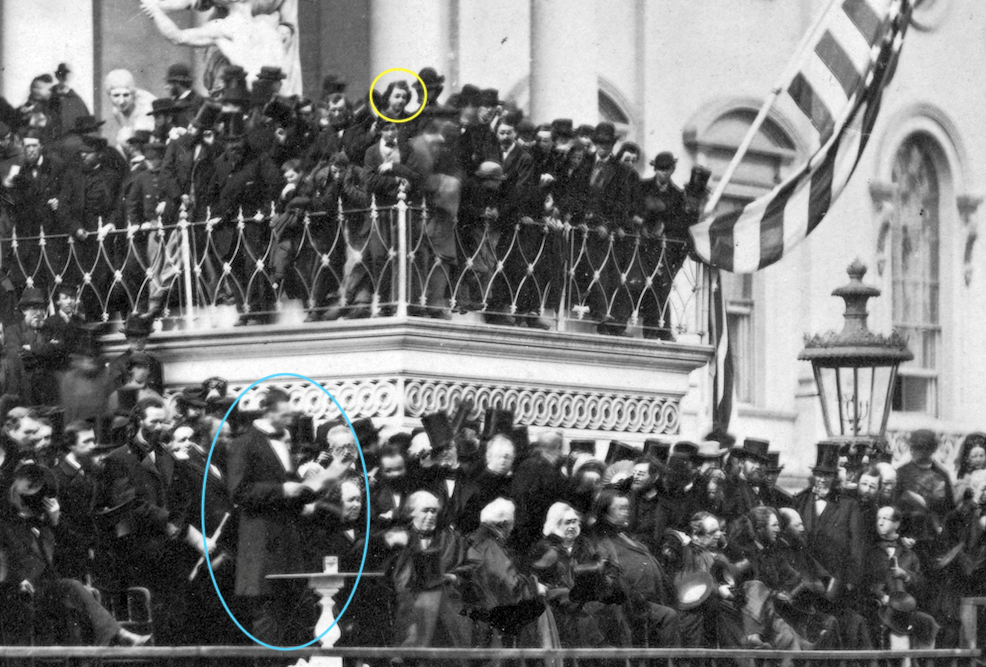

Lincoln’s second inauguration occurred on March 4, 1865. One man in attendance for this event was former slave and famed abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who later recalled, “I was present at the inauguration of Mr. Lincoln, the 4th of March, 1865. I felt then that there was murder in the air, and I kept close to his carriage on the way to the Capitol, for I felt that I might see him fall on that day. It was a vague presentiment.”10

As Lincoln was preparing to deliver his speech, something bizarre occurred in the rotunda of the Capitol, as recorded by Lincoln’s bodyguard Benjamin French:

As the procession was passing through the Rotunda toward the Eastern portico, a man jumped from the crowd into it behind the President. I saw him, & told Westfall, one of my Policemen, to order him out. He took him by the arm & stopped him, when he began to wrangle & show fight. I went up to him face to face, & told him he must go back. He said he had a right there, & looked very fierce & angry that we would not let him go on, & asserted his right so strenuously, that I thought he was a new member of the House whom I did not know & I said to Westfall ‘let him go.’ While we were thus engaged endeavouring to get this person back in the crowd, the president passed on, & I presume had reached the stand before we left the man.11

Lincoln made it safely to the Eastern portico and delivered what would become one of the most iconic presidential speeches in American history. With the end of the Civil War drawing nearer, Lincoln wanted to begin healing the open wounds of the nation and restore unity between the people of the North and the South. Rather than pass judgement upon Southern Americans or boast of an imminent Union victory, Lincoln meditates on the war as a divine punishment for the sin of slavery and encourages all Americans to accept the will of God and look to the future, working towards the healing of the nation.

The Almighty has his own purposes. “Woe unto the world because of offenses! for it must needs be that offenses come; but woe to that man by whom the offense cometh.” If we shall suppose that American slavery is one of those offenses which, in the providence of God, must needs come, but which, having continued through his appointed time, he now wills to remove, and that he gives to both North and South this terrible war, as the woe due to those by whom the offense came, shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a living God always ascribe to him? Fondly do we hope–fervently do we pray–that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn by the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said, “The judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.”

With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan–to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves, and with all nations.12

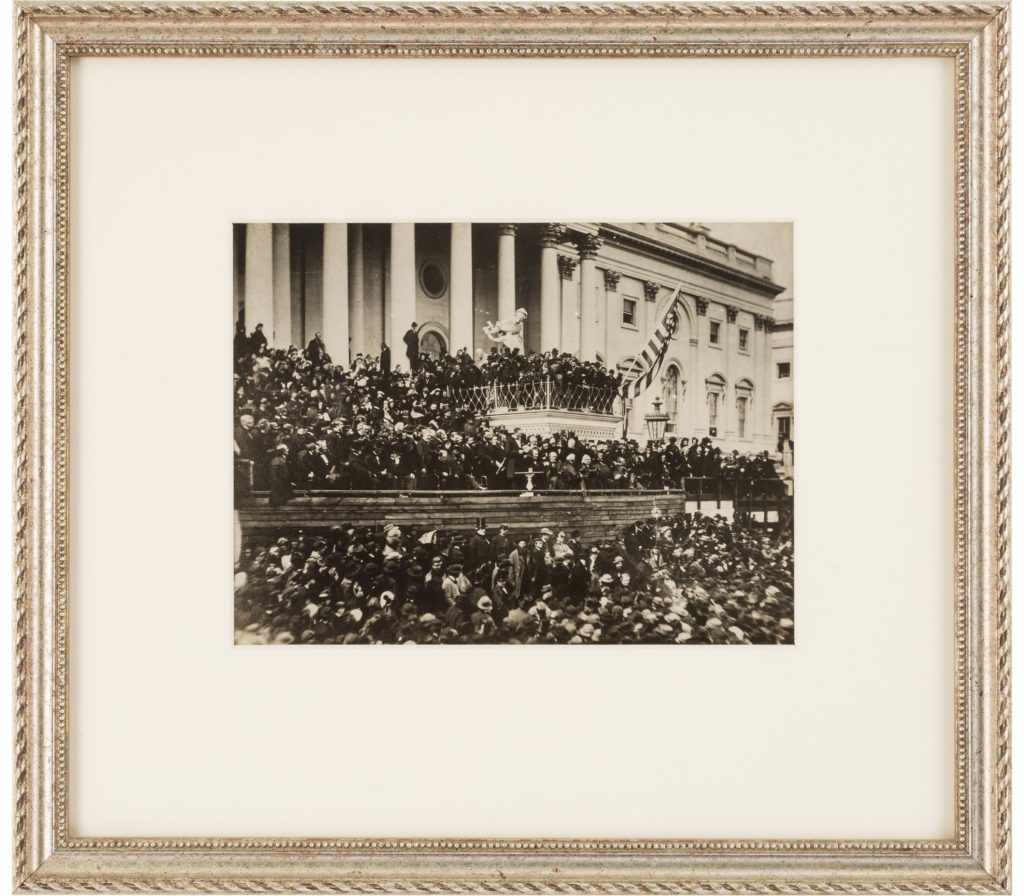

Lincoln delivered this speech from the steps of the Capitol building to a live crowd of between 30,000 and 40,000 people, among whom was John Wilkes Booth, who observed Lincoln’s speech from the balcony of the Capitol building.

Of course, this was not the first time Lincoln and Booth were in each other’s presence, nor would it be the last. Less than six weeks later, after the surrender of Confederate General Robert E. Lee to Ulysses S. Grant, Lincoln made one of his routine visits to Ford’s Theatre, this time seeing a performance of Our American Cousin on April 14, 1865. As Lincoln relaxed in the presidential box, John Wilkes Booth approached him from behind and shot the president in the back of the head with a pocket-sized derringer. With all attention focused on the mortally wounded president, Booth made his escape, and Lincoln was taken across the street to the Peterson house where he passed away shortly after 7:00 a.m. the next morning. (The American Journey Collection includes a piece of the jacket Lincoln was wearing when he was assassinated, which you can read more about here.)

The ensuing manhunt for John Wilkes Booth lasted for 12 days and involved nearly 1,000 Union soldiers, but he was eventually shot dead after being surrounded in a barn on April 26, 1865.

In the following investigation, as more information was uncovered, it became clear that the strange man French wrote about was indeed John Wilkes Booth himself, and that the event French describes on inauguration day was Booth’s first attempt to assassinate the president.

A fuller excerpt of French’s account reads:

I have little doubt that the intention was to assassinate the President on the 4th of March, & circumstances have been brought to my mind which almost convince me that, without knowing what I was doing, I was somewhat instrumental in preventing it. As the procession was passing through the Rotunda toward the Eastern portico, a man jumped from the crowd into it behind the President. I saw him, & told Westfall, one of my Policemen, to order him out. He took him by the arm & stopped him, when he began to wrangle & show fight. I went up to him face to face, & told him he must go back. He said he had a right there, & looked very fierce & angry that we would not let him go on, & asserted his right so strenuously, that I thought he was a new member of the House whom I did not know & I said to Westfall ‘let him go.’ While we were thus engaged endeavouring to get this person back in the crowd, the president passed on, & I presume had reached the stand before we left the man. Neither of us thought any more of the matter until since the assassination, when a gentleman told Westfall that Booth was in the crowd that day, & broke into the line & he saw a police man hold of him keeping him back. W. then came to me and asked me if I remembered the circumstance. I told him I did, & should know the man again were I to see him. A day or two afterward he brought me a photograph of Booth, and I recognized it at once as the face of the man with whom we had the trouble. He gave me such a fiendish stare as I was pushing him back, that I took particular notice of him & fixed his face in my mind, and I think I cannot be mistaken. My theory is that he meant to rush up behind the President & assassinate him, & in the confusion escape into the crowd again & get away. But, by stopping him as we did, the President got out of his reach. All this is mere surmise, but the man was in earnest, & had some errand, or he would not have so energetically sought to go forward.13

Ward H. Lamon, friend and self-appointed bodyguard of Lincoln, recorded the following in his biography of the president:

Lost opportunities, baffled hopes, exasperating defeats, served only to heighten the deadly determination of the plotters; and so matters drifted on until the day of Mr. Lincoln’s second inauguration. A tragedy was planned for that day which has no parallel in the history of criminal audacity, if considered as nothing more than a crime indeed,

Everybody knows what throngs assemble at the Capitol to witness the imposing ceremonies attending the inauguration of a President of the United States. It is amazing that any human could have seriously entertained the thought of assassinating Mr. Lincoln in the presence of such a concourse of citizens. And yet there was such a man in the assemblage. He was there for the single purpose of murdering the illustrious leader for who the second time was about to assume the burden of the Presidency. That man was John Wilkes Booth. Proof of his identity, and a detailed account of his movements while attempting to reach the platform where Mr. Lincoln stood, will be found in many affidavits, of which the following is a specimen: –

Robert Strong, a citizen of said County and District, being duly sworn, says that he was a policeman at the Capitol on the day of the second inauguration of President Lincoln, and was stationed at the east door of the rotunda, with Commissioner B. B. French, at the time the President, accompanied by the judges and others, passed out to the platform where the ceremonies of inauguration were about to begin, when a man in a very determined and excited manner broke through the line of policeman which had been formed to keep the crowd out. Lieutenant Westfall immediately seized the stranger, and a considerable scuffle ensued. The stranger seemed determined to get to the platform where the president and his party were, but Lieutenant Westfall called for assistance. The Commissioner closed the door, or had it closed, and the intruder was finally thrust from the passage leading to the platform which was reserved for the President’s party. After the President was assassinated, the singular conduct of this stranger on that day was frequently talked of by the policemen who observed it. Lieutenant Westfall proured a photograph of the assassin Booth soon after the death of the President, and showed it to Commissioner French in my presence and in the presence of several other policemen, and asked him if he had ever met that man. The commissioner examined it attentively and said: “Yes, I would know that face among ten thousand. That is the man you had a scuffle with on inauguration day. That is the same man.” Affiant also recognized the photograph. Lieutenant Westfall then said: “This is the picture of J. Wilkes Booth.” Major French exclaimed: “My God! What a fearful risk we ran that day!” …

From this sworn statement it will be seen that Booth’s plan was one of phenomenal audacity. So frenzied was the homicide that he determined to take the President’s life at the inevitable sacrifice of his own; for nothing can be more certain than that the murder of Mr. Lincoln on that public occasion, in the presence of a cast concourse of admiring citizens, would have been instantly avenged. The infuriated populace would have torn the assassin to pieces, and this the desperate man doubtless knew.14

Additionally, during the assassination trial, Booth’s fellow actor and Confederate sympathizer Sam Chester testified that Booth visited him in New York on April 7, one week prior to the assassination, where “he exclaimed, striking the table, ‘What an excellent chance I had to kill the president, if I had wished, on inauguration day!’”15

It seems as though Frederick Douglass’ senses were correct. Indeed, there was “murder in the air.”

The American Journey Vault is home to a copy of the famous photograph immortalizing this day taken from the original negative in the early 20th century – the only photograph in existence to feature both President Abraham Lincoln and his assassin John Wilkes Booth.

1. Leonard Grover. Lincoln’s Interest in the Theater. The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine. Vol. LXXVII. New Series: Vol. LV. November, 1908, to April 1909. (New York: The Century Co., 1909) 944. Here.

2. Leonard Grover. Lincoln’s Interest in the Theater. The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine. Vol. LXXVII. New Series: Vol. LV. November, 1908, to April 1909. (New York: The Century Co., 1909) 948. Here.

3. Alexander Hunter. New National Theater, Washington, D.C. A Record of Fifty Years. (Washington, D.C.: R.O. Polkinhorn & Son, Printers., 1885) 47. Here.

4. Gordon Samples. Lust for Fame: The Stage Career of John Wilkes Booth. (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1982) 125. Here.

5. John Hay. Lincoln and the Civil War in the Diaries and Letters of John Hay. (Westport: Negro Universities Press, 1972) 118. Here.

6. George Alfred Townsend. New York World. April 19, 1865

7. John Hay. Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay

8. George Alfred Townsend. New York World, April 19, 1865.

9. John Ellsler. The Stage Memories of John A. Ellsler. (Cleveland: The Rowfant Club, 1950) 129.

10. Frederick Douglass. Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln by Distinguished Men of His Time. (New York: North American Review: 1888). Here.

11. Benjamin Brown French. Letter from Benjamin Brown French to his son, Francis O. French. 1865. Here.

12. Thomas Mears Eddy. The Patriotism of Illinois: A Record of the Civil and Military History of the State in the War for the Union, with a History of the Campaigns in which Illinois Soldiers Have Been Conspicuous, Sketches of Distinguished Officers, the Roll of the Illustrious Dead, Movements of the Sanitary and Christian Commissions. (United States: Clarke & Company, 1865.) 526.

13. Benjamin Brown French. Letter from Benjamin Brown French to his son, Francis O. French. 1865. Here.

14. Ward Hill Lamon. Recollections of Abraham Lincoln, 1847-1865 (Washington, D.C.: The Editor, 1911)), 271-273. Here.

15. William Edwards. The Lincoln Assassination – The Trial Transcript. (William Edwards, 2012) 57-58. Here.