One of the most unique items in the American Journey Collection is this golden mourning ring containing a braided lock of George Washington’s hair. While it seems odd to people today, in the 18th and 19th centuries it was common for people to be given locks of hair as a sign of respect, affection, or as a memento. The practice fell out of use when it became more common for men to wear their hair short in the late 1800s.[1]

However, during the Revolutionary period it was quite common. Indeed, many of those in the founding generation exchanged locks of hair as memorials to departed friends and received requests from admirers. Abigail Adams and Mercy Otis Warren, both significant figures in the independence movement, exchanged locks with Adams writing:

I forward to you my dear friend a toke of love and friendship…the lock of hair you gave to me I have placed in an handkerchief pin set with pearl in the same manner with the ring and shall hold it precious.[2]

When Thomas Jefferson’s cousin, George Jefferson, died while traveling back to the United States, one of his companions wrote to Jefferson reporting the unfortunate news and explained, “I have enclosed a lock of hair for any of his friends who may wish it.”[3]Towards the end of his own life, Jefferson received many requests from people asking for a keepsake of the aged patriot. In responding to one of these appeals Jefferson wrote:

As, however, you express a desire to possess some memento of myself particularly, I take the liberty of offering you a miniature likeness of which I ask your acceptance. It will be a token of more meaning than a simple lock of hair whitened with the frosts of 79 winters.[4]

Jefferson’s general practice was to include a likeness alongside his hair.[5] Similarly, Benjamin Franklin would send a similar package to people requesting mementos. One recipient of such a package, the artist Georgiana Shipley, thanked the American philosopher in superlative terms:

How shall I sufficiently express my raptures on receiving your dear delightful letter & most valuable present. The pleasure I felt was increased if possible at the sight of the beloved little lock of hair, I kissed both that & the picture a 1000 times. The miniature is admirably painted…it is my very own dear Doctor Franklin himself, I can almost fancy you are present.[6]

Noted patriot and painter John Trumbull had an extensive collection of locks from friends and associates which included hair from George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, General Lafayette, General Israel Putnam, General Anthony Wayne, General Benedict Arnold, and Aaron Burr.[7]

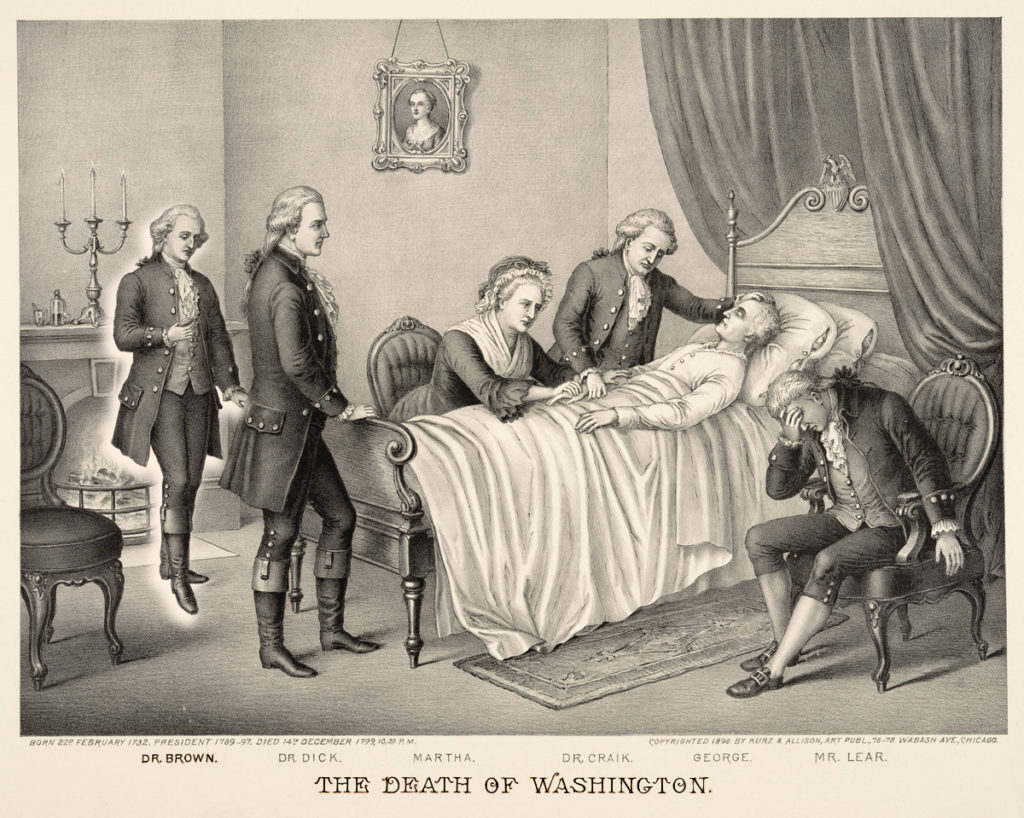

Upon George Washington’s death in 1799, his hair immediately began to carry with it a greater significance as a lasting relic of the “Father of the Country.” Indeed, after the funeral, the widowed Martha Washington would wear, “a mourning locket or ring containing a lock of the president’s hair.”[8] With Washington being perhaps the most beloved man in America at the time of his death, requests for relics flooded in to Martha and Tobias Lear, the personal secretary of Washington—many of these asked for strands of hair.[9]

Additionally, Martha and other relatives took it upon themselves to send relics of the departed President to family friends and other notables. When the Marquis de Lafayette returned to America for the first time since the Revolutionary War in 1824 he made sure to visit Mount Vernon and the tomb of his dear friend. After paying his respects to Washington, Lafayette was presented, “with a gold ring, containing some of the hair of the great man, and we returned to the house where our companions awaited us.”[10]One of Washington’s grandsons sent a similar relic to Simon Bolivar after the liberation of much of South America from Spanish rule.[11]

In subsequent generations, rings holding Washington’s hair became marks of distinction and continued to be used as gifts to notable leaders. For example, John Hay, private secretary to Lincoln and Secretary of State under William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt, gave to a recently elected President Rutherford B. Hayes a, “gold ring into which he had cast a strand of hair from the head of George Washington,” which he had received from one of Hamilton’s sons.[12]

In a very unique instance, General James Grant Wilson, a historian, relic hunter, and veteran of the Civil War, obtained, “a certain wonderful ring he wore containing a lock of hair from the heads of Washington, Lincoln, Hamilton, Wellington, Napoleon, and Gen. Grant, which he told me his relic-admiring lady friends had often kissed very reverently.”[13] This particular ring represents an ambitious crossover of historical personalities.

The American Journey Vault is home to one such golden mourning ring. The hair contained in this ring was sent to Alexander Hamilton immediately upon the passing of Washington in 1799. When Hamilton died in 1804, possession of the hair was broken up amongst his wife and surviving children. This lock of hair remained with Mrs. Hamilton who then gave it to her personal physician, Dr. William Hall, who took care of her during her final illness. Dr. Hall then passed it to his daughter, who gave it to her son, Hall Colgate. When Colgate died his wife gave it to her brother, James Davis. Davis passed it to William McCarthy, who then presented it to Leo M. Bernstein. After Bernstein’s death in 2008, the American Journey Experience acquired it from auction.

Outside of our collection, only a handful of these rings still exist.[14] The ring at the Grand Rapids Public Museum contains a portion of Washington’s hair which has been weaved in a very similar manner to ours.[15] The museum at Colonial Williamsburg holds a very interesting piece which has hair from both George and Martha Washington weaved together.[16]

The Hamilton family probably received the most Washington locks and remained associated with the relics for hundreds of years. One of Alexander Hamilton’s granddaughters wore a, “pearl locket containing a lock of Washington’s hair,” to the centennial celebration of Washington’s first inauguration.[17] Another lock originally given to Hamilton is recorded in the Washington Memorial Chapel is 1921.[18]

[1] “About Locks of Hair,” The Collector: A Current Record of Art, Bibliography, Antiquarianism, Etc., Vol. 6, No. 8 (February 15, 1895), 128. Here.

[2] Abigail Adams, “To Mercy Otis Warren,” December 30, 1812, Founders Online (accessed February 18, 2022): https://founders.archives.gov/?q=%22lock%20of%20hair%22&s=1111311111&sa=&r=10&sr=.

[3] Fontaine Maury, “To Thomas Jefferson,” July 18-29, 1812, The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Retirement Series (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008), 5.259. Here.

[4] Thomas Jefferson, “To Duncan Forbes Robinson,” December 11, 1821, Founders Online (accessed February 18, 2022): https://founders.archives.gov/?q=%22lock%20of%20hair%22&s=1111311111&sa=&r=13&sr=.

[5] See also, Thomas Jefferson, “To Palmira Johnson,” September 27, 1823, Founders Online (accessed February 18, 2022): https://founders.archives.gov/?q=%22lock%20of%20hair%22&s=1111311111&sa=&r=14&sr=.

[6] Georgiana Shipley, “To Benjamin Franklin,” February 3, 1780, The Papers of Benjamin Franklin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 31.444. Here.

[7] Ed. Frossard, The Trumbull Gallery: Earliest Works of John Trumbull (Boston: T. R. Marvin & Son, 1894), 27-28. Here.

[8] D. Tulla Lightfoot, The Culture and Art of Death in 19th Century America (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, 2019), 68. Here.

[9] Matthew Costello, “‘The Property of the Nation’: Democracy and the memory of George Washington, 1799-1865,” Ph.D. Dissertation (Marquette University, 2016), 35, 259. Here.

[10] Auguste Levasseur, Lafayette in America in 1824 and 1825: Or, Journal of a Voyage to the United States (Philadelphia: Carey and Lea, 1829), 1.182. Here.

[11] Matthew Costello, “‘The Property of the Nation’: Democracy and the memory of George Washington, 1799-1865,” Ph.D. Dissertation (Marquette University, 2016), 270. Here.

[12] John Taliaferro, All the Great Prizes: The Life of John Hay, from Lincoln to Roosevelt (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2012), 171. Here.

[13] Josiah Collins Pumpelly, “General James Grant Wilson,” The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, Vol. 45, No. 3 (July 1914): 207. Here.

[14] See, for example, the following auction records: “Yellow Gold Ring with George Washington’s Hair,” Live Auctioneers (accessed February 18, 2022), here; “Hairwork Memorial Ring Reportedly with a Plaited Lock of George Washington’s Hair,” Skinner Inc (accessed February 18, 2022): here; “American Gold and Pearl Mourning Ring Containing Hair Stated to be of George Washington,” Lot-Art (accessed February 18, 2022): here.

[15] “George Washington Mourning Ring,” 1799, Grand Rapids Public Museum (accessed February 18, 2022): https://grpmcollections.org/Detail/objects/142862.

[16] “Mourning Ring with George and Martha Washington’s Hair,” 1802, Colonial Williamsburg (accessed February 18, 2022): https://emuseum.history.org/objects/963/mourning-ring-with-george-and-martha-washingtons-hair;jsessionid=15532E01EE74EB8F036CA8A6508F6139.

[17] The Washington Centenary Celebrated in New York, April 29, 30 – May 1, 1889 (New York: The Tribune Association, 1889), 29. Here.

[18] W. Herbert Burk, The Valley Forge Guide: Historical and Topographical Guide to Valley Forge (North Wales: Norman B. Nuss, 1921),121. Here.