Washington’s Surveying Compass he likely acquired in his early teenage years and used throughout his life. Prior to becoming a military and political leader, Washington served as a surveyor in the Virginia frontier.

Perhaps more than any other person, George Washington truly deserves the title as the “Father of our Country.” Americans know him as one our nation’s Founding Fathers, our first U.S. president, and as Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army in the Revolutionary War. Washington is doubtlessly one of the most iconic figures in American history. However, people know little about his exploits before his providential leadership during the struggle for independence.

Born in Popes Creek, Westmoreland County Virginia on February 22, 1732, to Augustine and Mary Washington, George was the first of six children, yet had 5 older half-siblings from his father’s first marriage to Jane Butler, who passed away in 1728.[1] Washington received an inferior early education in comparison to his eldest siblings who attended the affluent Appleby Grammar School in England. At 15, his formal education halted altogether due to his family’s financial hardship.[2] Washington privately lamented this fact, writing to David Humphreys, an aide-to-camp during the war, that , “I am conscious of a defective education.”[3] Unlike Washington, many of the Founding Fathers were highly educated men who were well-versed in fields such as philosophy, public oration, science, and law. John Adams, later the second president of the United States, noted Washington’s lack of education to fellow signer of the Declaration, Dr. Benjamin Rush:

That Washington was not a scholar is certain. That he was too illiterate, unlearned, unread, for his station and reputation is equally past dispute. He had derived little knowledge from reading; none from travel, except in the United States, and excepting one trip in his youth to one of the West India Islands and directly back again. From conversation in public and private, he had improved considerably and by reflection in his closet, a good deal. He was indeed a thoughtful man.[4]

Knowing this insecurity of Washington’s, it makes perfect sense that in a diary entry in 1785 he pledged a sum of $100 dollars a year to support the education of George Washington Craik, the son of close friend Dr. James Craik, in his pursuits of becoming a lawyer.[5] One could surmise that, knowing of his own educational deficiencies, he wanted to ensure that a child named after him would not suffer the same misfortune. He later wrote to James Craik that, “with much I can say, I never felt the want of money so sensibly since I was a boy of 15 years old,” recounting the season which led to his early withdrawal from schooling.[6]

Despite Washington’s lack of education, however, he did learn the fundamentals of mathematics and trigonometry, applying those skills exceptionally well by becoming a surveyor.[7] Growing up, Washington spent much time at Belvoir, a plantation owned by William Fairfax. Fairfax was the father-in-law to Washington’s older brother Lawrence. Over time, Fairfax obtained a father-like position in his life and Washington later recalled that, “that the happiest moments of my life had been spent there.”[8]

Fairfax had a substantial impact on young Washington, and possibly helped solidify Washington’s fondness of mapmaking after hiring him to survey land in the Shenandoah Valley in 1747.[9] Marking his first substantial contract, the 16-year-old Washington made numerous journal entries discussing the difficulties encountered and lessons learned over the course of the trip. In March of 1747, Washington made the following entry:

Tuesday 15th. We set out early with intent to run round the said land but being taken in a rain & it increasing very fast obliged us to return. It clearing about one o’clock & our time being too precious to loose we a second time ventured out & worked hard till night & then returned to Pennington’s we got our suppers & was lighted in to a room & I, not being so good a woodsman as the rest of my company, striped myself very orderly & went in to the bed as they called it when to my surprise I found it to be nothing but a little straw—matted together without sheets or anything else but only one thread bear blanket with double its weight of vermin such as lice fleas &c. I was glad to get up (as soon as the light was carried from us) & put on my cloths & lay as my companions. Had we not have been very tired, I am sure we should not have slept much that night. I made a promise not to sleep so from that time forward choosing rather to sleep in the open air before a fire as will appear hereafter.[10]

After successfully completing the survey, Washington proved himself to be competent and soon became quite successful at a remarkably young age. At the age of 17, he was commissioned by the College of William & Mary to become Culpeper County’s first official surveyor.[11] Two days after taking the oath of public office, he immediately went to work and surveyed his first plot of 400 acres on Flat Run, east central of Culpeper County.[12]

For reasons unknown, Washington ended his tenure as Culpepper county’s surveyor the next year but continued to work extensively throughout the Virginia frontier and earned a, “reputation for fairness, honesty, and dependability.”[13] By the time of his death in 1799, Washington had completed nearly 200 surveys, out of which only 75 have been found.[14]

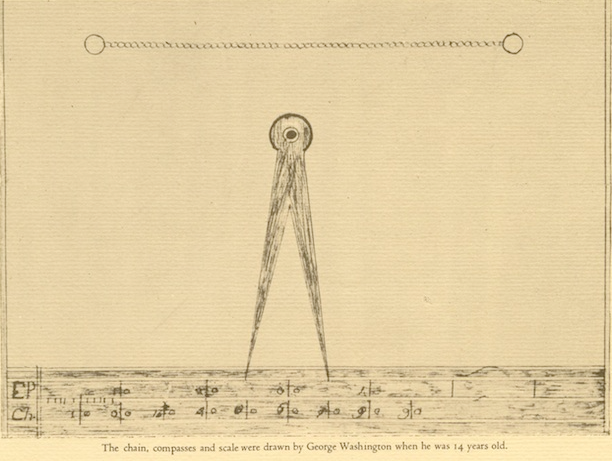

Within the American Journey Vault is one of George Washington’s cartographer’s compass which he undoubtedly used during the early days of his surveying career. Acquired from the heirs of the Washington family itself, this compass represents one of the most significant items from the foundational years of Washington’s life. Indeed, when Washington was only 14 years old he made a sketch of the surveying equipment he would need and among other items is the depiction of a compass quite similar to the one preserved in the American Journey Vault.[15] Although today we refer to it as simply a compass, back in Washington’s time it would be called either a “pair of compasses” or “compasses” for short. In the book Washington learned how to survey from, William Leybourn’s The Compleat Surveyor, a pair of compasses was frequently needed to solve the geometrical problems.[16] It is possible that Washington even used this compass to finish these exercises.

Soon after achieving success as a surveyor, however, Washington began his military career, being inspired by his admiration for his older half-brother Lawrence who had served as adjutant general of the Virginia Militia.[17] Washington vied for a position in the military and was eventually appointed the commander of a military district in Virginia by Lt. Gov. Robert Dinwiddie in 1753.[18] It would only be a few months into 21-year-old Washington’s new career that his life would change forever.

On 16 June 1753, Dinwiddie transmitted information concerning French forces expanding into frontier regions close to British claims, stating that:

I hope you will think it necessary to prevent the French taking possession of the lands on the Ohio, so contiguous to our settlements, or indeed in my private opinion they ought to be prevented making any settlements to the westward of our present possessions.[19]

In August 1753, orders came directly from King George II specifically authorizing Dinwiddie to build forts around the Ohio River and informing Dinwiddie of his orders should the French not disperse:

if you shall find, that any number of persons, whether Indians, or Europeans, shall presume to erect any fort or forts within the limits of our province of Virginia.…You are to require of them peaceably to depart, and not to persist in such unlawful proceedings, & if, notwithstanding your admonitions, they do still endeavor to carry on any such unlawful and unjustifiable designs, we do hereby strictly charge, & command you, to drive them off by force of arms.[20]

With explicit orders from the King, it was now Dinwiddie’s duty to find someone willing and able to journey through the northern wilderness to meet the French. However, candidates were not plentiful. Ultimately, Dinwiddie chose Washington for the expedition. It was likely that Washington was selected for this position due not only to his favor with high officials at the time, but also to his invaluable knowledge of the northern parts of the area from his surveying experience. Washington explained to his father in 1755 that, “I was employed to go a journey in the Winter (when I believe few or none would have undertaken it).”[21] Washington was also surprised at his selection, saying “It was an extraordinary circumstance that so young and inexperienced a person be employed on a negotiation with which the subjects of the greatest importance were involved.”[22]

His journey to the French was long and treacherous with unpredictable weather. Washington recounted that “at the most inclement season,” he and his party traveled 250 miles “through an uninhabited wilderness country” to “within 15 miles of Lake Erie in the depth of winter, when the whole face of the earth was covered with snow and the waters covered with ice.”[23]

After many significant events which can be read in Washington’s journal, he was captured by French forces and taken to Fort Le Boeuf. There, he handed the demands of King George to fort commander Saint-Pierre, but the French leader rejected the king’s request to abandon their position.[24] This eventually leads to the beginning of the French and Indian War in which Washington would gain his most important military experience. The journey makes Washington famous in Virginia and London, marking his debut great exposure to the public eye. Washington’s experiences both as a surveyor and as a frontier soldier during the French and Indian War uniquely prepared him for his upcoming role in the American Revolution. Although he did not have the “book learning” which many of the other Founding Fathers enjoyed, Washington was educated in the school of hard-won experience which perhaps mattered a great deal more when it came to defeating British tyranny on the battlefield and establishing American liberty.

[1] Ron Chernow, Washington: A Life (New York City: The Penguin Press, 2010) 5-7.

[2] Ron Chernow, Washington: A Life (New York City: The Penguin Press, 2010) 18.

[3] George Washington, “To David Humphreys,” July 25, 1785, The Papers of George Washington, Confederation Series (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1994), 3.148-150. Here.

[4] John Adams, “To Benjamin Rush,” April 22, 1812, Founders Online (Accessed February 17, 2022): Here.

[5] George Washington, [Diary] August 1785, Founders Archives (Accessed Feb 8 2022) Here

[6] George Washington, From George Washington to James Craik, 4 August 1788 (Accessed Feb 8 2022) Here

[7] Ron Chernow, Washington: A Life (New York City: The Penguin Press, 2010), 10-12.

[8] George Washington, “To George William Fairfax,” February 27, 1785, The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources, 1745-1799 (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1938), 28.83. Here.

[9] J. M. Toner, “Introduction,” in Journal of My Journey Over the Mountains (Albany: Joel Munsell’s Sons, 1892), 11-12. Here.

[10] George Washington, Journal of My Journey Over the Mountains (Albany: Joel Munsell’s Sons, 1892), 26-27. Here.

[11] “George Washington’s Professional Survey, 22 July 1749 – 25 October 1752,” The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia), 1.9. Here.

[12] “George Washington’s Professional Survey, 22 July 1749 – 25 October 1752,” The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia), 1.9. Here.

[13] Edward Redmond, “Washington as a Public Land Surveyor,” Library of Congress (accessed February 17, 2022), here.

[14] Edward Redmond, “Washington as a Public Land Surveyor,” Library of Congress (accessed February 17, 2022), here.

[15] Lawrence Martin, The George Washington Atlas (Washington: George Washington Bicentennial Commission, 1932), image on Index page 2. Here.

[16] William Leybourn, The Compleat Surveyor: Or, the Whoe Art of Surveying of Land (London: Samuel Cunn, 1722), 11 and passim. Here.

[17] Ron Chernow, Washington: A Life (New York City: The Penguin Press, 2010), 31-33.

[18] Ron Chernow, Washington: A Life (New York City: The Penguin Press, 2010), 31-33.

[19] Robert Dinwiddie, quoted in Editorial Note in, “Commission from Robert Dinwiddie,” October 30, 1753, The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1983), 1.57. Here.

[20] Quoted in Editorial Note in, “Commission from Robert Dinwiddie,” October 30, 1753, The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1983), 1.57.Here

[21] The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 1, 7 July 1748 – 14 August 1755, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1983, 351–354.]

[22] The Diaries of George Washington, Vol. 1, ed. Donald Jackson. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1976. Here

[23] Ron Chernow, Washington: A Life (New York City: The Penguin Press, 2010) 31-33

[24] Ron Chernow, Washington: A Life (New York City: The Penguin Press, 2010) 26-27, 31.