Out of all the people who journeyed to America on the Mayflower in 1620, few were as influential as Pilgrim leader William Brewster. Born sometime in either 1566 or 1567 somewhere around Scrooby, Nottinghamshire, England, during the last years of the English Interregnum. Growing up in the Growing up during the reign of the famous King James (who authorized the translation of the Bible into English), William Brewster later became involved in a Christian sect which broke away from the state-mandated Church of England and became known as Separatists. Pilgrim leader William Bradford explained that a substantial group of likeminded individuals, “whose hearts the Lord had touched with heavenly zeal for His truth.…joined themselves (by a covenant of the Lord, into a church estate, in the fellowship of the Gospel, to walk in all His ways.”1

During this time, Brewster earned distinction among the congregation and Bradford notes that Brewster was, “a man beloved and honored amongst them, and who took great pains in teaching and dispensing the word of God unto them.”2 Eventually the Separatist congregation actually began meeting in Brewster’s residence at Scrooby Manor in Nottinghamshire, and Brewster soon, “afterwards was chosen an Elder of the church and lived with them till old age.”3 Due to this Brewster’s standing in the church, not to mention the fact that he was also the local paymaster, he was often among those targeted by the British government whenever they attempted to suppress the illegal church congregation and was imprisoned for an extended period of time.4

However, after repeated abuse and sustained oppression by the government, the Separatists decided to flee to Holland where they could enjoy more religious freedom away from the Church of England. To do so was no easy task because the English government attempted to prevent them from doing so, at every turn harrying them, imprisoning leaders, and altogether attempting to coerce the dissenters to forsake their faith and rejoin the Church of England. Nevertheless, “in the end, notwithstanding all these storms of opposition, they all got over at length, some at one time, and some at another, and some in one place, and some in another, and met together again according to their desires, with no small rejoicing.”5

Ultimately, the fugitives gathered in Leiden, Holland, which became their temporary refuge for the next twelve years. Brewster was actually one of the last to leave England as he had, “stayed to help the weakest over before,” he himself would make his escape.6 Despite not living in England anymore, they nevertheless still continued to persuade more of their countrymen to separate from the Church of England. The primary way in which they pursued such a goal was thorough the printing of banned religious material which would then be smuggled back into England. The printer of this so-called Pilgrim Press was none other than Elder William Brewster.

Beginning in 1616, Brewster launched an aggressive publishing campaign which produced anti-regime books at a staggering rate. In 1618 alone they published seven entire books criticizing the practices of the Church of England.7 Needless to say, their contraband writing and “illegal” speech infuriated the King and officials in the Church of England. Although in the entirely different country of Holland, they still were not free from the King of England’s reach and he sent out agents to uncover who was responsible for these “dangerous” opinions.8

Upon discovering the press of William Brewster in Leiden, King James began to pressure the governing authorities to crack down on the Pilgrim enclave. Brewster became a wanted fugitive and one agent of the British King reported that, “I have used all diligence to enquire after Brewster.…I understand he prepares to settle himself at a village called Leerdorp, not far from Leyden, thinking there to be able to print prohibited books without discovery, but I shall lay wait for him, both there and in other places.” 9

With the noose quickly tightening around them, the haven which the Separatists found in Holland was now all but gone. The Danish government was amenable to work with England in delivering the congregation up to their persecutors. Negotiations, however, had already been started to attempt to secure passage to the New World but now the success of such a mission became altogether more urgent. Through unrelenting efforts and the grace of God they secured an agreement which provided a place for them to practice their beliefs without interference from the King although in return they had to pay fifty-percent of their earnings for the first seven years.10 With this agreement finally agreed to, the Separatists prepared to sail to, “a land so barbarous and so abandoned by the world that they might yet be permitted to live there in their manner and pray to God in freedom.”11

It was decided that their pastor, John Robinson, would stay behind with the majority of the congregation while a smaller number would be the pathfinders on the pilgrimage. The group which would soon become known as the Pilgrims, however, specifically requested that, “the elder, Mr. Brewster, to go with them.”12With this plan in motion there were still numerous obstacles which had to be surmounted. Originally there had been two boats, the Mayflower and the Speedwell, but the latter ship repeatedly sprung leaks—possibly due to sabotage—forcing even more people to have to stay behind. By the time the Mayflower, now alone, carried its collection of Pilgrims and Strangers (the name given to the other colonists who weren’t a part of the dissenters) only 104 souls embarked from the shores of the Old World.13

Prior to the departure, however, their pastor John Robinson gave them this admonition encouraging them to pursue more seriously than ever their spiritual duties. Robinson explained that:

First, as we are daily to renew our repentance with our God, specially for our sins known, and generally for our unknown trespasses, so doth the lord call us in a singular manner upon occasions of such difficulty and danger as lieth upon you, to a both more narrow search and careful reformation of our ways in His sight, lest He, calling to remembrance our sins forgotten by us or unrepented of, take advantage against us, and in judgement leave us for the same to swallowed up in one danger or another; whereas, on the contrary, sin being taken away by earnest repentance, and the pardon thereof from the Lord sealed up unto a man’s conscience by His Spirit, great shall be his security and peace in all dangers, sweet his comforts in all distresses, with happy deliverance from all evil, whether in life or in death.14

With this encouragement, that hardy band in the hull of the Mayflower truly became Pilgrims as they made the treacherous voyage, leaving behind all that was familiar and venturing into a vast wilderness months behind schedule which meant that they would land in America in the dead of winter.

Upon arriving in the New World, Brewster immediately began fulfilling his duties as the de facto religious leader and Elder of the church. On Sunday, January 21, 1621, Brewster led the Pilgrims in their first communal church service to be held on land instead of on the Mayflower.15 Before they disembarked, however, the Pilgrims had to first decide upon a form of government by which everyone would agree to abide by. In addition to arriving late, they had also been blown far off course landing well North of the land which had been approved for them to settle. This occurrence had led some of the crew and other passengers who were not members of the Pilgrims to consider themselves beyond the reach of law and order. To rectify this potentially disastrous situation, they gathered together to “covenant and combine” themselves into a civil body politic.

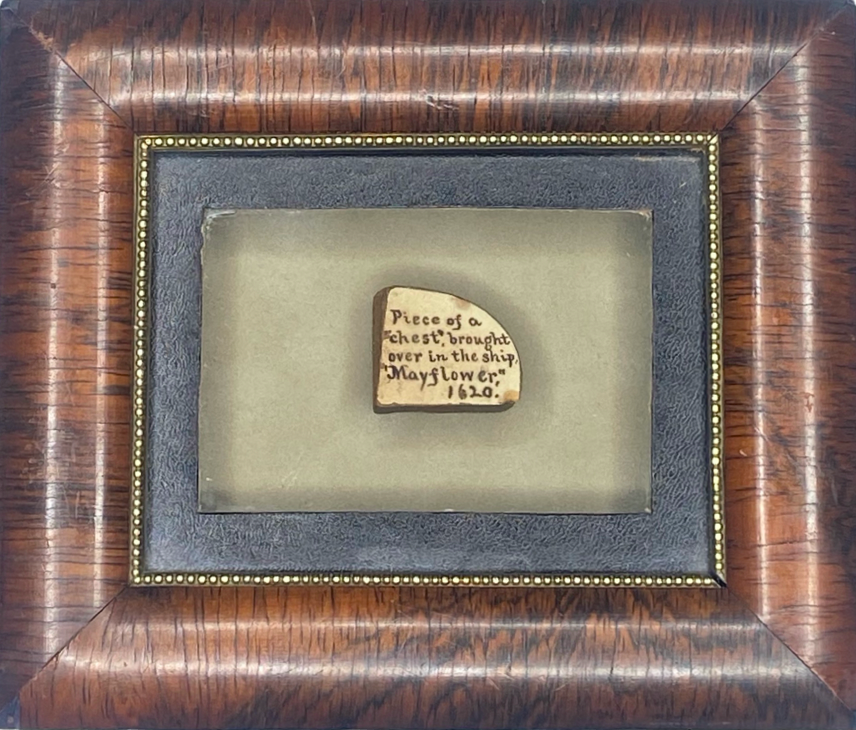

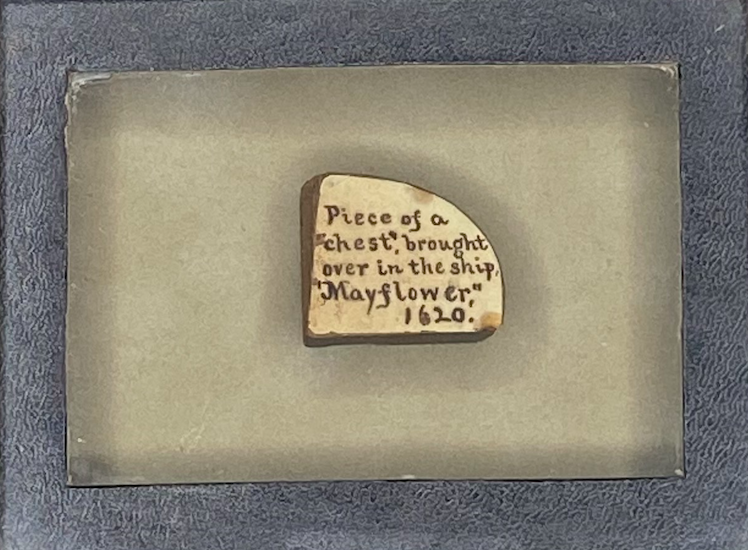

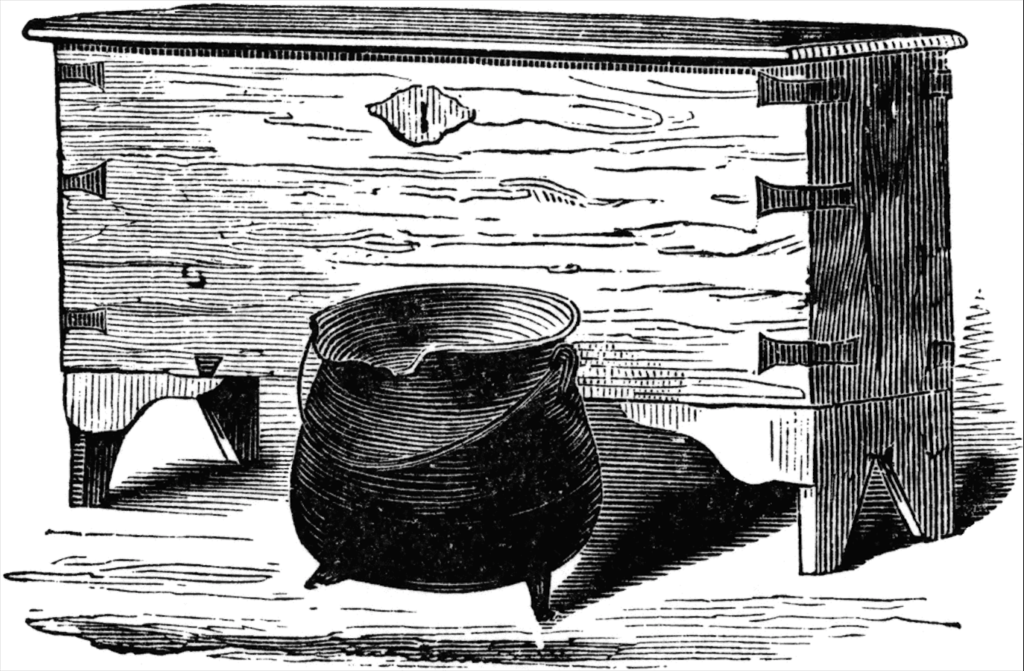

The most likely candidate to draft up such a plan of government was William Brewster as he was the only one on board who had any sort of college education.16 Therefore, Elder Brewster was quite possibly the penman of the Mayflower Compact. Additionally, early historians think that Brewster would have used his travel chest for a writing desk.17 It is even likely that Brewster’s chest was the platform upon which the rest of the passengers on the Mayflower signed the Compact themselves. Noted historian Benson Lossing explained that, “It was on the lid of Elder Brewster’s chest that this constitution of government was signed. They then proceeded to elect John Carver for governor. Thus was erected the first republic—a pure democracy—in America.”18

It was upon his chest then, that the seeds of American constitutionalism were first planted by the pen of a fugitive wanted on account of his sincere desire to worship God as he saw proper. The document begins by invoking the Creator, opening with the simple phrase, “In the name of God, Amen.” Continuing, Brewster and the Pilgrims thought it best to explain their reasons for coming to the New World at all, and wrote that:

Having undertaken for the glory of God, and advancement of the Christian and honor of our king and country, a voyage to plant the first colony in the Northern parts of Virginia, do by these presents solemnly and mutually in the presence of God, and one of another, covenant and combine ourselves together into a civil body politic, for our better ordering and preservation and furtherance of the ends aforesaid.19

With these words, “the first model of our state governments, and indeed of all our representative institutions in this western world, was formed, and went into operation.”20 Behind much of the origins and developments which laid the stage for such an event is owed to the actions of Elder William Brewster.

Brewster continued to serve as a religious leader for the Pilgrims in America until his death at the age of 84 on April 10, 1644. While much could be said concerning his activities in America for the 24 years after his journey on the Mayflower, the eulogy offered by Bradford perhaps best explains the influence which Brewster had upon the Pilgrims:

Mr. William Brewster was a man that had done and suffered much for the Lord Jesus and the gospel’s sake, and hath born his part in weal and woe, with this poor persecuted church above thirty-six years, in England, Holland, and in this wilderness; and done the Lord and them faithful service in his place and calling.…He afterwards lived in good esteem in his own country, and did much good, until the troubles of those times enforced his remove into Holland, and so into New England, and was in both places of singular use and benefit to the church and people of Plymouth whereof he was; being eminently qualified for such work as the Lord had appointed him unto, of which should I speak particularly as I might, I should prove tedious: I shall content myself therefore only to have made honorable mention in general of so worthy a man.21

The American Journey Experience collection is the proud home of an original fragment from the chest which Brewster carried with him on the Mayflower in 1620. Although it is impossible to know with absolute certainty, it is more likely than not that upon this chest that the first self-governing document in America was written and signed. George Bancroft noted the significance of the occasion saying that, “In the cabin of the Mayflower, humanity recovered its rights, and instituted government on the basis of ‘equal laws’ for the ‘general good.’”22

After Brewster died the chest was passed down through the family until it became the possession of Joseph Brewster—William Brewster’s great, great grandson.23 The chest then passed to Ruth Brewster and upon the death of her husband, Samuel Sampson, the relic was given to a Mr. Plin Day. In 1844, Mr. Day sold the chest to Rev. Thomas Robbins who served as the librarian of the Connecticut Historical Society.24 Today, the rest of the chest resides in the Pilgrim Hall Museum collections.25 It is likely that this piece was removed during the early 1800s if not at an earlier period when such a practice was especially common.

Although this piece of the Brewster Chest is but a tiny fragment, it represents the very foundation of American civil liberties and ideals of self-government. Indeed, it provides a very apt illustration of Braford’s famous reflection that:

Out of small beginnings greater things have been produced by His hand that made all things of nothing, and gives being to all things that are; and as one small candle may light a thousand, so the light here kindled hath shone to many, yea in some sort to our whole nation; let the glorious name of Jehovah have all the praise.26

[1] William Bradford, History of Plymouth Plantation, 1620-1647 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1912), 1.20-22. Here.

[2] William Bradford, History of Plymouth Plantation, 1620-1647 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1912), 2.79. Here.

[3] William Bradford, History of Plymouth Plantation, 1620-1647 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1912), 1.35. Here.

[4] See footnote 2 in, William Bradford, History of Plymouth Plantation, 1620-1647 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1912), 1.31. Here.

[5] William Bradford, History of Plymouth Plantation, 1620-1647 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1912), 1.31. Here.

[6] William Bradford, History of Plymouth Plantation, 1620-1647 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1912), 1.37. Here.

[7] Stephen Tomkins, The Journey to the Mayflower (New York: Pegasus, 2020), 320.

[8] Ashbel Steele, Chief of the Pilgrims: Or The Life and Time of William Brewster (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott and Co., 1857), 171-180, here.

[9] Quoted in Footnote 1 on, William Bradford, History of Plymouth Plantation, 1620-1647 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1912), 1.89. Here.

[10] William Bradford, History of Plymouth Plantation, 1620-1647 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1912), 1.105. Here.

[11] Alexis de Tocqueville, trans. Harvey Mansfield, Democracy in America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), 32.

[12] William Bradford, History of Plymouth Plantation, 1620-1647 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1912), 1.98. Here.

[13] “List of Mayflower Passengers,” Society of Mayflower Descendants in the State of New York: Fourth Record Book (October 1912): 167-178, here.

[14] John Robinson, “Certain Useful Advertisements sent in a Letter Written by a Discreet Friend Unto the Planters in New England, at Their First Setting Sail from Southampton, Who Earnestly Desireth the Prosperity of that Their New Plantation,” in George Cheever, The Pilgrim Fathers: Or, The Journal of the Pilgrims at Plymouth, New England, in 1620 (Glasgow: William Collins, 1849), 89-90. Here.

[15] Edward Winslow, Mourt’s Relation or Journal of the Plantation at Plymouth (Boston: John Kimball Wiggin, 1865), 78. Here.

[16] Ashbel Steele, Chief of the Pilgrims: Or The Life and Time of William Brewster (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott and Co., 1857), 40-42, 227. Here.

[17] Thomas White and Samuel White, Ancestral Chronological Record of the William White Family, From 1607-8 to 1895 (Concord: Republican Press Association, 1895), 12; Joseph Eldridge and Theron Wilmot Crissey, History of Norfolk Litchfield County, Connecticut, 1744-1900 (Everett: Massachusetts Publishing Company, 1900), 400; Edmund J. Carpenter, The Pilgrims and their Monument (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1911), 212.

[18] Benson J. Lossing, Harpers’ Popular Cyclopaedia of United States History (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1893), 1.481.

[19] Quoted in, William Bradford, History of Plymouth Plantation, 1620-1647 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1912), 1.191. Here.

[20] Ezra Stiles Ely, The Migration of the Pilgrims and of Their Posterity (Philadelphia: United States Gazette, 1818), 8-9.

[21] William Bradford, in Nathaniel Morton, The New-England’s Memorial (Plymouth: Allen Danforth, 1826), 132-134. Here.

[22] George Bancroft, A History of the United States (Boston: Brown, Little, and Company, 1853), 1.310.

[23] Emma C. Brewster Jones, The Brewster Genealogy, 1566-1907 (New York: The Grafton Press, 1908), 1.xl.

[24] Emma C. Brewster Jones, The Brewster Genealogy, 1566-1907 (New York: The Grafton Press, 1908), 1.xl.

[25] “Collections & Exhibitions: Furniture,” Pilgrim Hall Museum (accessed January 26, 2022): https://pilgrimhall.org/ce_funiture.htm.

[26] William Bradford, History of Plymouth Plantation, 1620-1647 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1912), 2.117. Here.