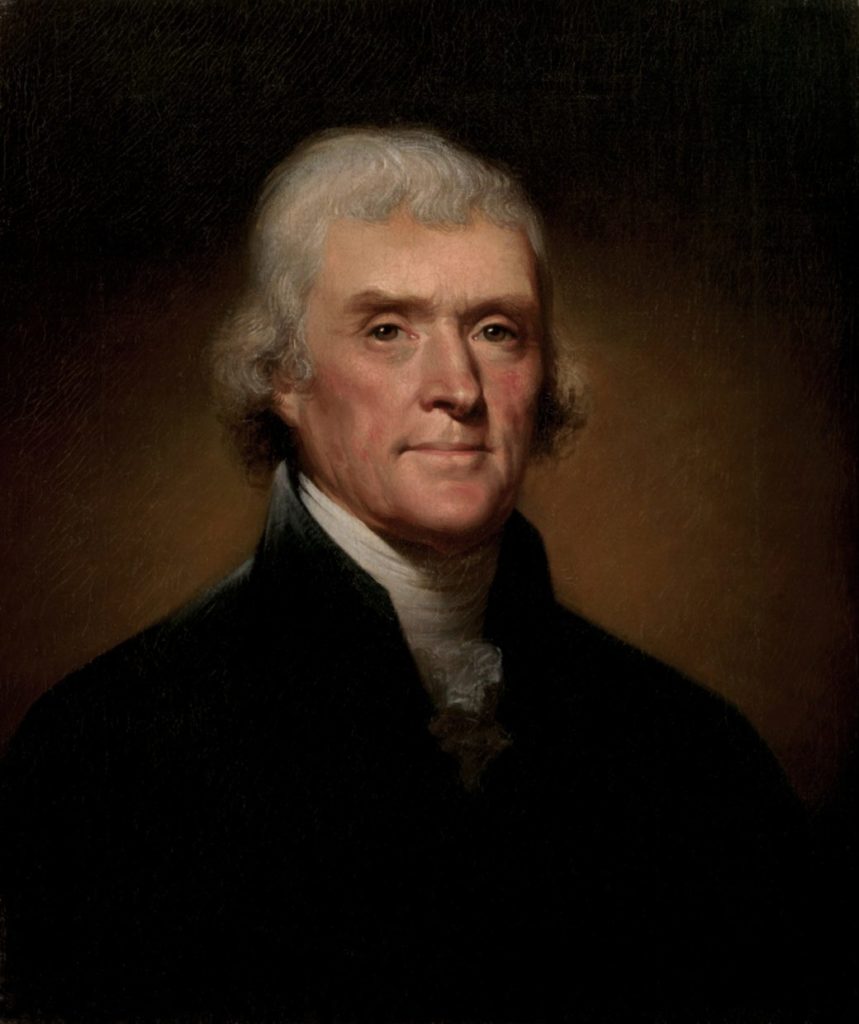

The Declaration of Independence stands as the original founding document of the United States, boldly proclaiming the nation’s separation from Great Britain and igniting a revolution that would reshape history. More than a mere statement of independence, it embodies the American ethos and the promise of liberty. Thomas Jefferson, its principal author, described it as “an expression of the American mind,”1 capturing the core ideals that would define the nation. Yet, while the Declaration remains a guiding standard by which America measures itself, the story of its creation is often overlooked.

On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee, a delegate from Virginia, boldly read before the Second Continental Congress a resolution stating, “that these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and that the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.”2 Up to this point the prospect of independence had merely been an idea which bounced around the minds of some but on a whole was considered impractical, too audacious, and in some cases unnecessary. Members of the Continental Congress such as John Dickinson still hoped for a peaceful resolution of the issues and a restoration to the British Empire.3

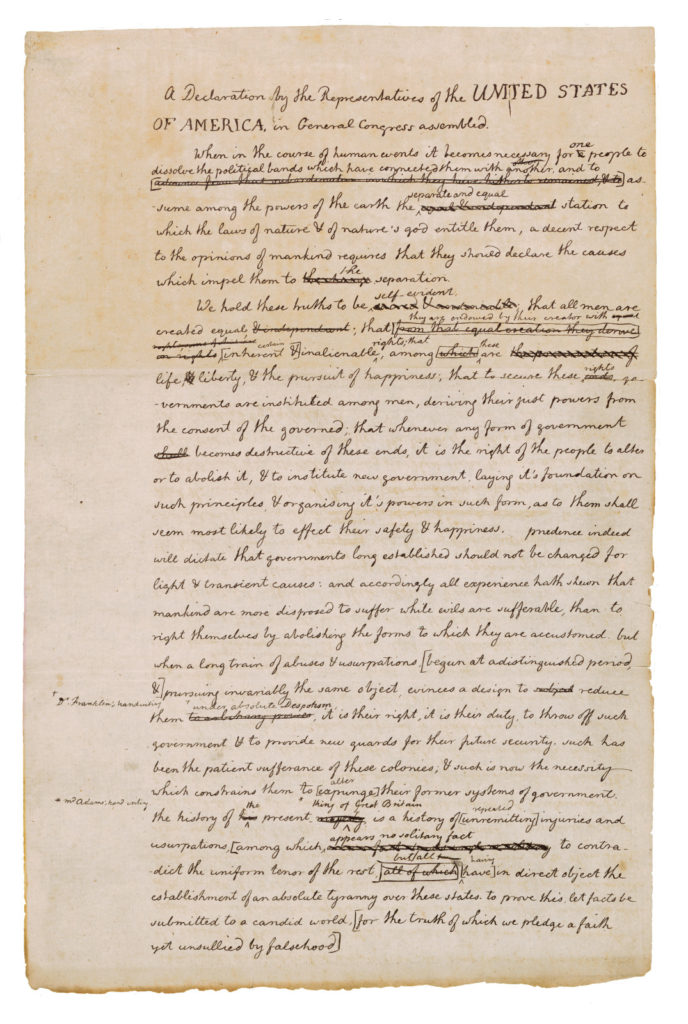

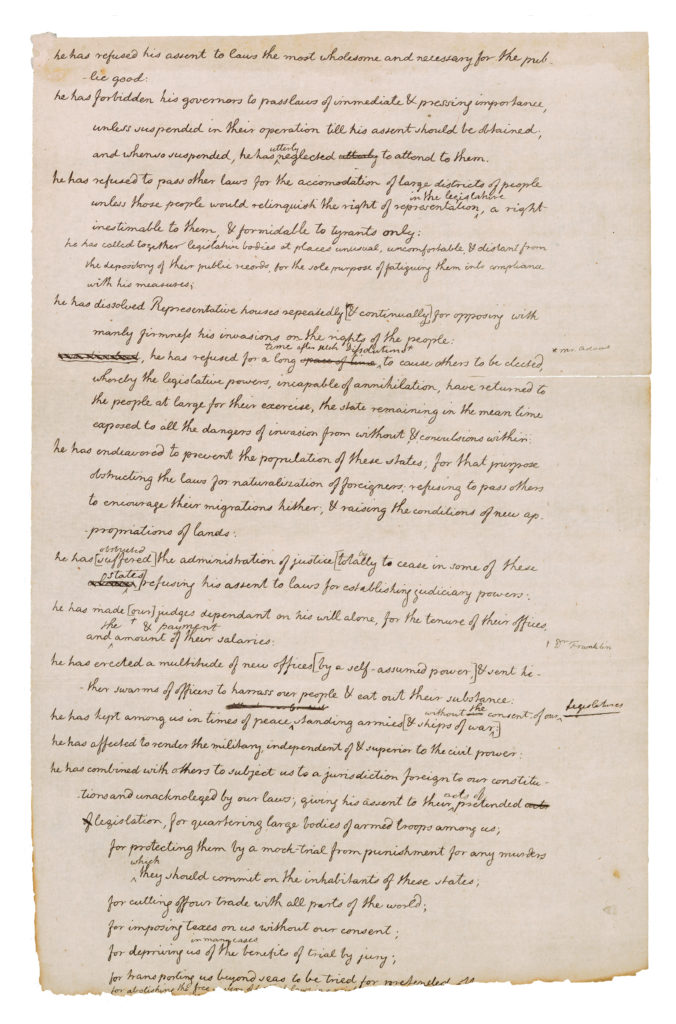

Four days later (June 11), a young politician from Virginia named Thomas Jefferson was appointed to the committee charged with drafting a formal statement declaring the colonies’ independence from Great Britain. The committee also included John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston, but the task of drafting the document fell almost exclusively upon Jefferson due to the excellence of his previous writings.

In an 1823 letter to friend and political ally James Madison, an elderly Jefferson wrote that the other members of the committee:

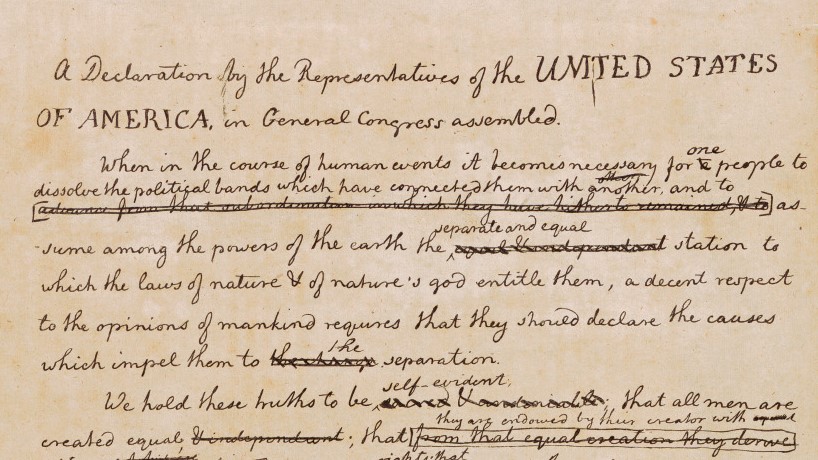

Unanimously pressed on myself alone to undertake the draught. I consented; I drew it; but before I reported it to the committee, I communicated it separately to Dr. Franklin and Mr. Adams requesting their corrections; because they were the two members of whose judgments and amendments I wished most to have the benefit before presenting it to the Committee; and you have seen the original paper now in my hands, with the corrections of Doctor Franklin and Mr. Adams interlined in their own hand writings—their alterations were two or three only, and merely verbal I then wrote a fair copy, reported it to the Committee, and from them, unaltered to Congress.4

When Jefferson did present his first draft to Adams and Franklin, the more experienced statesmen were greatly impressed. John Adams, explained that upon reading the proposed first draft:

I was delighted with its high tone, and the flights of oratory with which it abounded, especially that concerning negro slavery; which, though I knew his Southern brethren would never suffer to pass in Congress, I certainly would never oppose.5

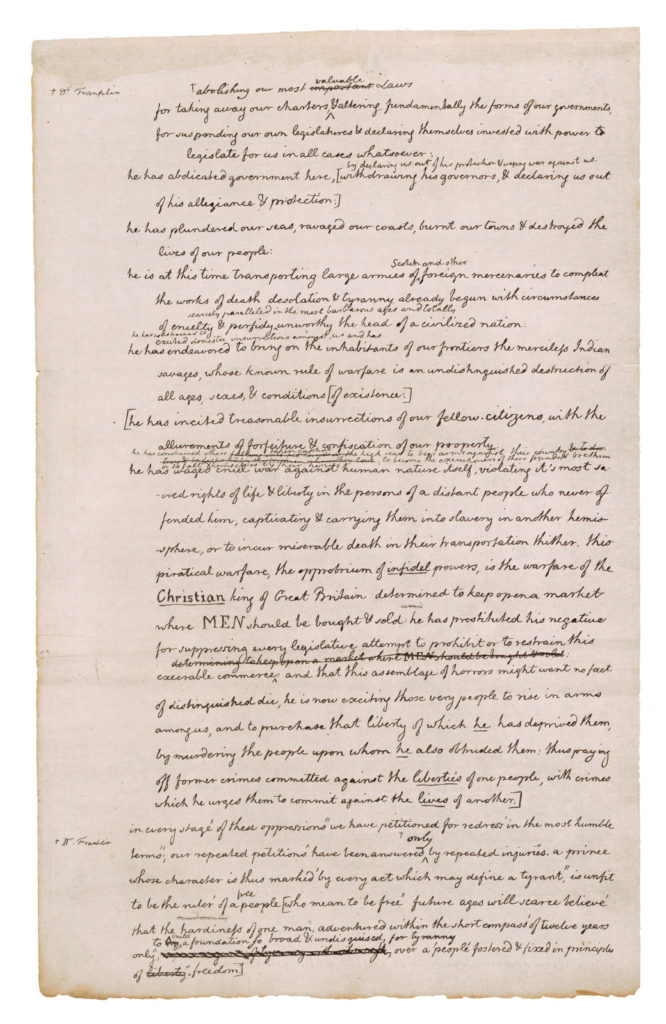

In the Declaration, Jefferson outlines numerous grievances against the King on behalf of the colonies. Among these, John Adams highlights the longest grievance in Jefferson’s draft, which contains some of the most striking language beyond the opening sections. Jefferson directly condemns King George III for compelling the American colonies to participate in the slave trade, despite repeated efforts to restrict, prohibit, and abolish it. In his original draft, he asserts:

He [King George] has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating it’s most sacred rights of life & liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating & carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere, or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither. this piratical warfare, the opprobrium of infidel powers, is the warfare of the Christian king of Great Britain. determined to keep open a market where MEN should be bought & sold, he has prostituted his negative for suppressing every legislative attempt to prohibit or to restrain this execrable commerce: and that this assemblage of horrors might want no fact of distinguished die, he is now exciting those very people to rise in arms among us, and to purchase that liberty of which he has deprived them, & murdering the people upon whom he also obtruded them; thus paying off former crimes committed against the liberties of one people, with crimes which he urges them to commit against the lives of another.6

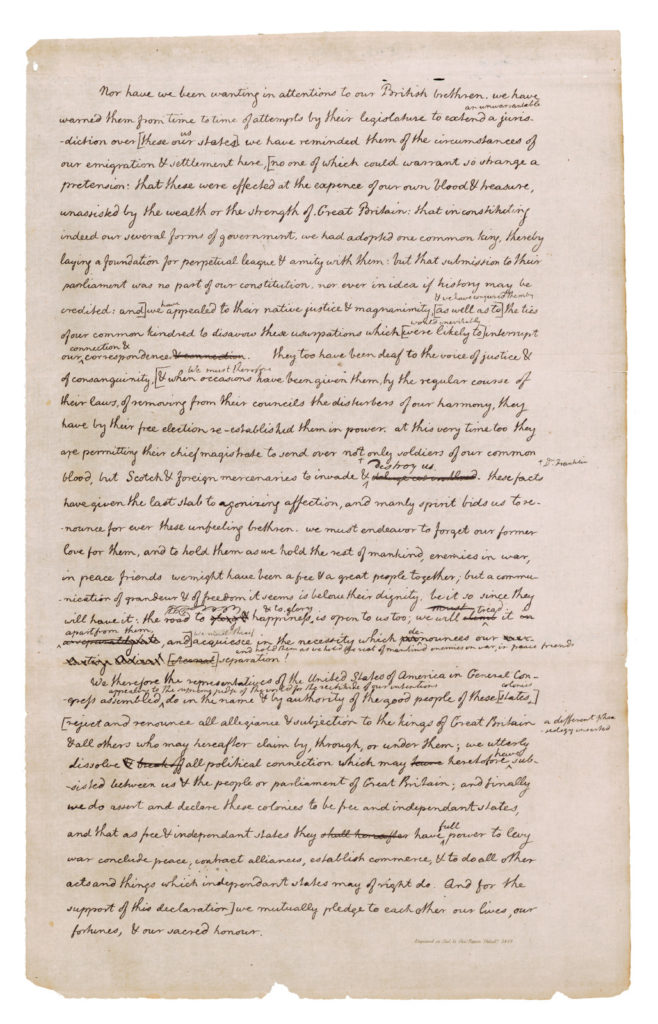

While most of Franklin’s and Adam’s edits were minor, Congress made substantial revisions after Jefferson presented it to them on June 28, 1776. The change Jefferson and the others fought the hardest against was the removal of this anti-slave trade grievance. Almost fifty years later Jefferson fondly recalled that Adams, who after the Revolution became his staunchest political rival, had, “supported the Declaration with zeal and ability, fighting fearlessly for every word of it.”7

When the Declaration came before the general body of Congress, just as Adams had feared, some of the Southern states with entrenched slavery objected to the anti-slave trade grievance. Years later, Jefferson begrudgingly recalled that:

The pusillanimous idea that we had friends in England worth keeping terms with, still haunted the minds of many. For this reason those passages which conveyed censures on the people of England were struck out, lest they should give them offense. The clause too, reprobating the enslaving the inhabitants of Africa, was struck out in complaisance to South Carolina and Georgia, who had never attempted to restrain the importation of slaves, and who on the contrary still wished to continue it. Our northern brethren also I believe felt a little tender under those censures; for tho’ their people have very few slaves themselves yet they had been pretty considerable carriers of them to others.8

Jefferson’s anti-slave trade clause was removed because the final Declaration of Independence required unanimous approval from all represented states. The opposition of just two states was enough to strike it from the document, as consensus was essential for adoption. John Hancock, the president of the Continental Congress at the time, is reported to have explained that, “We must be unanimous…there must be no pulling different ways; we must all hang together.”9 To which Franklin characteristically replied, “Yes…we must, indeed, all hand together, or most assuredly we shall all hang separately.”10 The more interesting observation is, however, that although two states voted against the grievance, that means that all the other states concurred with the idea on at least some level—a supermajority.

.

This fact contradicts the modern narrative pushed by radical education initiatives such as the 1619 Project. In the headlining essay by lead author Nikole Hannah-Jones, she claims that, “one of the primary reasons the colonists decided to declare their independence from Britain was because they wanted to protect the institution of slavery.”11 She goes on to say that:

The United States is a nation founded on both an ideal and a lie. Our Declaration of Independence, signed on July 4, 1776, proclaims that “all men are created equal” and “endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights.” But the white men who drafted those words did not believe them to be true for the hundreds of thousands of black people in their midst.12

However, the briefest examination of Jefferson’s original draft shows this assertion to be patently false. In the anti-slave trade grievance, Jefferson deliberately wrote that King George was, “determined to keep open a market where MEN should be bought and sold.”13 The only word outside of the title which Jefferson completely capitalizes is “MEN” in direct reference to the African slaves. Jefferson deliberately highlights the humanity of enslaved individuals, affirming that they, too, are encompassed within the declaration that “all men are created equal.” His words were not intended solely for white men but extended to enslaved people and individuals of all races.

Going further, prior to the Revolution, several northern colonies tried to pass bans on the slave trade, which were then vetoed by Royal Governors acting on behalf of the King.14 It was British policy to promote the slave trade and any efforts from the colonies to restrict it was heavily resisted.15 In 1773, Benjamin Franklin complained of such a fact, writing while on a trip in England that:

I have since had the satisfaction to learn that a disposition to abolish slavery prevails in North America; that many of the Pennsylvanians have set their slaves at liberty; and that even the Virginia Assembly have petitioned the king for permission to make a law for preventing the importation of more into that Colony. This request, however, will probably not be granted, as their former laws of that kind have always been repealed.16

The year after Franklin’s letter, representatives led by George Washington met in Fairfax, Virginia, and passed a resolution stating that, “during our present difficulties and distress [with England]…we take this opportunity of declaring our most earnest wishes to see an entire stop to such a wicked, cruel, and unnatural [slave] trade.”17

Another Founding Father, George Mason (Framer of the Constitution and Father of the Bill of Rights), also remembered how England had blocked attempts to end the slave trade and explained:

Another Founding Father, George Mason (Framer of the Constitution and Father of the Bill of Rights), also remembered how England had blocked attempts to end the slave trade and explained:

Under the Royal Government this evil was looked upon as a great oppression, and many attempts were made to prevent it; but the interest of the African merchants prevented its prohibition. No sooner did the Revolution take place, than it was thought of. It was one of the great causes of our separation from Great Britain.18

Jefferson, Franklin, Washington, and Mason were far from being the only voices in the Founding era who remembered that the budding anti-slavery sentiments in America was one of the significant reasons for separating from the British Empire. For example, one delegate to the Virginia ratifying convention remarked that, “it was one cause of the complaints against British tyranny, that this trade was permitted.”19

Even British political leaders recognized the validity of the American’s grievance, remarking that the American colonies, “have made laws to prohibit the importation of them [African slaves]; but these laws have always had negative [i.e. veto] put upon them here because of their tendency to hurt our [English] Negro trade.”20 Many Americans wanted independence from Great Britain so they would have the freedom to ban the slave trade in their colonies. Indeed, many Americans wanted to even abolish slavery entirely. Upon separating from England, several of the states began the process of ending slavery on their own. In 1777, Vermont included in their new constitution a prohibition of slavery, and in the 1780 constitution of Massachusetts they laid the groundwork for complete emancipation.21 Similarly, in 1780, Pennsylvania passed a law for the gradual abolition of slavery.22 By 1804 all of the New England states as well as New York and New Jersey had either completely abolished slavery or passed laws for the gradual abolition of it.23 Places like Vermont declared in their legal code that, “the idea of slavery is expressly and totally exploded from our free government.”24 Even pro-slavery politicians recognized that, “it was the fashion of the day to favor the liberty of slaves.”25

Even British political leaders recognized the validity of the American’s grievance, remarking that the American colonies, “have made laws to prohibit the importation of them [African slaves]; but these laws have always had negative [i.e. veto] put upon them here because of their tendency to hurt our [English] Negro trade.”20 Many Americans wanted independence from Great Britain so they would have the freedom to ban the slave trade in their colonies. Indeed, many Americans wanted to even abolish slavery entirely. Upon the separating from England, several of the states began the process of ending slavery on their own. In 1777, Vermont included in their new constitution a prohibition of slavery, and in the 1780 constitution of Massachusetts they laid the groundwork for complete emancipation.21 Similarly, in 1780, Pennsylvania passed a law for the gradual abolition of slavery.22 By 1804 all of the New England states as well as New York and New Jersey had either completely abolished slavery or passed laws for the gradual abolition of it.23 Places like Vermont declared in their legal code that, “the idea of slavery is expressly and totally exploded from our free government.”24 Even pro-slavery politicians recognized that, “it was the fashion of the day to favor the liberty of slaves.”25

Despite the fact that the anti-slave trade did not make it into the final version of the Declaration of Independence, it is important to note that the Declaration nevertheless became a beacon of antislavery thought. Jefferson’s now famous line, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal,” practically became a motto of the abolitionist movement. The Declaration of Independence was understood as a strong indictment against slavery in the decades following the war by citizens and statesmen.26 Today, despite attempts to undermine its meaning and significance, the Declaration continues to stand as one of the most important calls to liberty, human rights, and freedom in the history of the world. The American Journey Experience collection is home to a special 1829 steel plate engraving of Jefferson’s first draft which prominently features the anti-slave trade grievance. After Jefferson passed away on July 4, 1826 (which just so happened to be the 50th anniversary of the Declaration), work began on publishing a collection of his most important papers. In 1829, his grandson published the Memoir, Correspondence, and Miscellanies from the Papers of Thomas Jefferson in 1829.27 He considered the first draft of the Declaration of Independence to be of such great historical importance that one of these facsimiles was included in every copy. The copy in the American Journey Experience collection was one printed for inclusion in that publication.[Read a full transcript of the First Draft here.]

1. Thomas Jefferson, “To Henry Lee,” May 8, 1825, The Writings of Thomas Jefferson (Washington: Taylor and Maury, 1854), 7.407. Here.

2. Library of Congress, “A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774-1875. Volume V. 1776. June 5–October 8. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1906), 425. Here.

3. For an example of this attitude, see the Olive Branch Petition from July 5, 1775, in, “Late Petition to the King,” The Constitutions of the Several Independent States of America…And the Petition of Congress to the King (London: J. Stockdale, 1783), xxvii. Here.

4. Thomas Jefferson, “To James Madison,” August 30, 1823, The Works of Thomas Jefferson (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1905), 12.307. Here.

5. John Adams, “To Timothy Pickering, 6 August 1822,” The Works of John Adams, eds. Charles Francis Adams (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1850), 514.

6. Thomas Jefferson, The Works of Thomas Jefferson, edited by Paul Leicester Ford (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904), 210-211.

7. Thomas Jefferson, “To James Madison,” August 30, 1823, The Works of Thomas Jefferson (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1905), 12.308. Here.

8. Thomas Jefferson, “Memoir,” Memoir, Correspondence, and Miscellanies from the Papers of Thomas Jefferson (Charlottesville: F. Carr and Co., 1829), 15. Here.

9. Jared Sparks, editor, The Works of Benjamin Franklin (Boston: Tappan and Dennet, 1844), 1.408

10. Jared Sparks, editor, The Works of Benjamin Franklin (Boston: Tappan and Dennet, 1844), 1.408

11. Nikole Hannah-Jones, “Our Democracy’s Founding Ideals Were False When They Were Written. Black Americans Have Fought to Make Them True,” The New York Times (August 14, 2019), 18.

12. Nikole Hannah-Jones, “Our Democracy’s Founding Ideals Were False When They Were Written. Black Americans Have Fought to Make Them True,” The New York Times (August 14, 2019), 16.

13. Thomas Jefferson, The Works of Thomas Jefferson, edited by Paul Leicester Ford (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904), 210-211.

14. Arthur Zilversmit, The First Emancipation: The Abolition of Slavery in the North (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1967), 63, 93.

15. Arthur Zilversmit, The First Emancipation: The Abolition of Slavery in the North (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1967), 49.

16. Benjamin Franklin, “To Dean Woodward, April 10, 1773,” The Writings of Benjamin Franklin, eds. Albert Henry Smyth(New York: The MacMillan Company, 1906), 6.39.

17. George Washington, “Fairfax County Resolves,” The Writings of George Washington, eds. Jared Sparks (Boston: Russell, Odiorne, and Metcalf, 1834),2.494.

18. George Mason, in Jonathan Eliot, The Debates, Resolutions, and Other Proceedings in Convention, on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution (Washington: Printed by the Editor, 1828),2.335.

19. Jonathan Eliot, The Debates, Resolutions, and Other Proceedings in Convention, on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution (Washington: Printed by the Editor, 1828),2.336.

20. Richard Price, Two Tracts on Civil Liberty, the War with America, and the Debts and Finances of the Kingdom (London: T. Cadell, 1778), 71.

21. Vermont Constitution, 1786, Article I, “Declaration of Rights;” Article I, “Declaration of Rights,” A Constitution or Frame of Government Agreed Upon by the Delegates of the People of the State of Massachusetts-Bay (Boston: Benjamin Edes and Sons, 1780), 7.

22. “Chapter DCCCLXX. An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery,” Laws of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, From the Fourteenth Day of October, One Thousand Seven Hundred, to the Twentieth Day of March, One Thousand Eight Hundred and Ten (Philadelphia: John Bioren, 1810), 1.492-493.

23. See, for example, A Constitution or Frame of Government Agreed Upon by the Delegates of the People of the State of Massachusetts-Bay (Boston: Benjamin Edes and Sons, 1780), 7, Article I, “Declaration of Rights”; and An Abridgement of the Laws of Pennsylvania, ed. Collinson Read, (Philadelphia: 1801), 264-266, Act of March 1, 1780; The Public Statue Laws of the State of Connecticut (Hartford: Hudson and Goodwin, 1808), Book I, 623-625, Act passed in October 1777; and Rhode Island Session Laws (Providence: Wheeler, 1784), 7-8, Act of February 27, 1784; The Constitutions of the Sixteen States (Boston: Manning and Loring, 1797), 50, New Hampshire, 1792, Article I, “Bill of Rights”; The Constitutions of the Sixteen States (Boston: Manning and Loring, 1797), 249, Vermont Constitution, 1786, Article I, “Declaration of Rights.” Vermont had technically passed laws abolishing slavery prior to joining the United States in 1777, but reaffirmed them upon their acceptance into the Union; Laws of the State of New York, Passed at the Twenty-Second Session, Second Meeting of the Legislature (Albany: Loring Andrew, 1798), 721-723, Act passed on March 29, 1799; Laws of the State of New Jersey Compiled and Published Under the Authority of the Legislature, ed. Joseph Bloomfield (Trenton: James J. Wilson, 1811), 103-105, Act passed February 15, 1804; E. Littell, Littell’s Living Age, Third Series Vol. XXX (Boston: Littell, Son, and Company, 1865) 196; Richard Newman, Freedom’s Prophet: Bishop Richard Allen, the AME Church, and the Black Founding Fathers (New York: New York University Press, 2008), 39; James Schouler, History of the United States of America, Under the Constitution (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1882), 2.62-64.

24. “An Act to prevent the sale and transportation of Negroes and Mulattoes out of this State” (1786), in Records of the Council of Safety and Governor and Council of the State of Vermont (Montpelier: J. & J. M. Poland, 1873), 92.

25. James Jackson, in Thomas Lloyd, The Congressional Register (New York: Harrison and Purdy, 1789), 1.308.

26. For the reception of the Declaration as an instrument of freedom see, Philip F. Detweiler, “Congressional Debate on Slavery and the Declaration of Independence, 1819-1821,” The American Historical Review Vol. 63, No. 3 (April 1958): 598-616.

27. Thomas Jefferson, Memoir, Correspondence, and Miscellanies from the Papers of Thomas Jefferson (Charlottesville: F. Carr and Co., 1829).