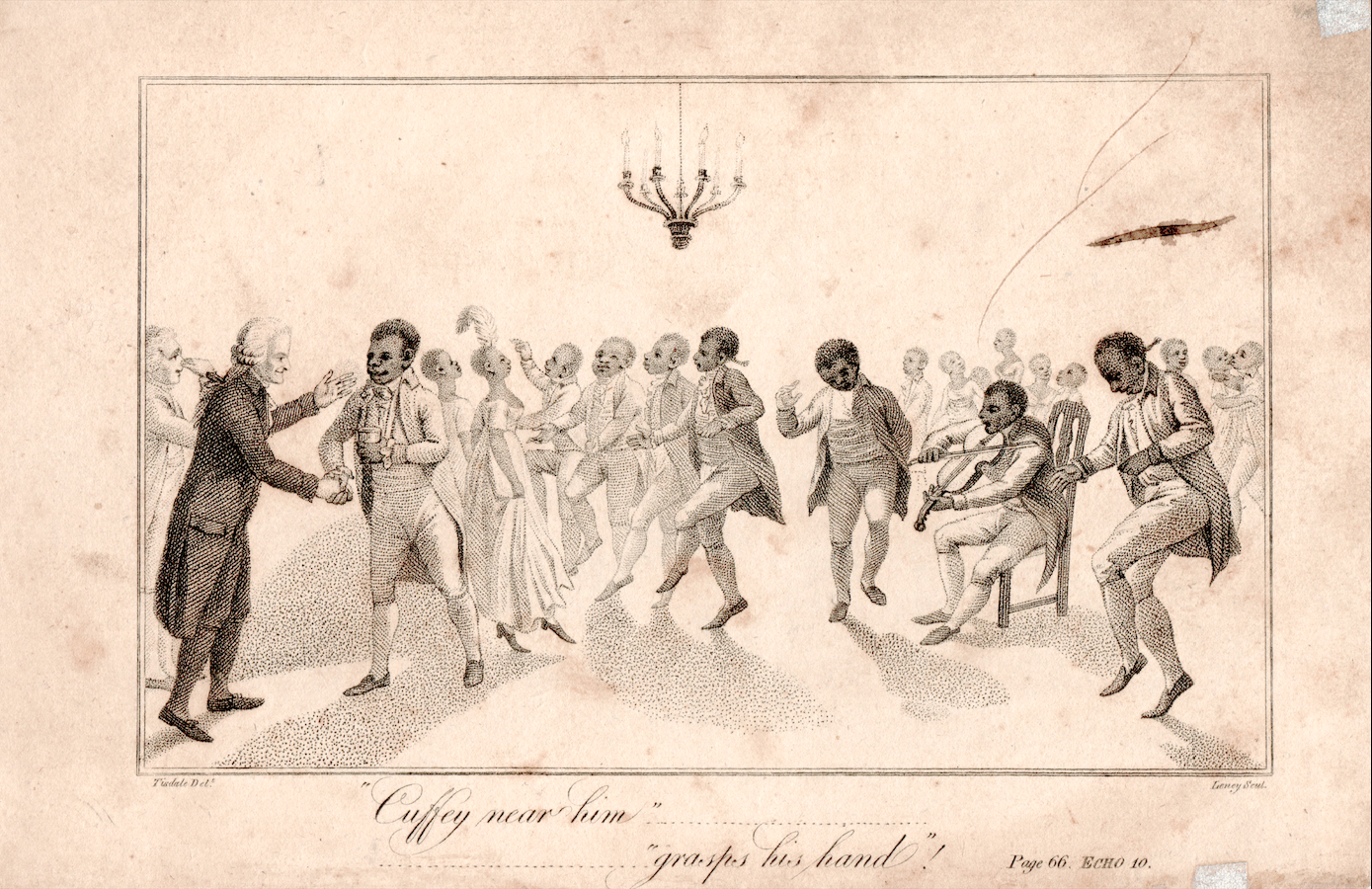

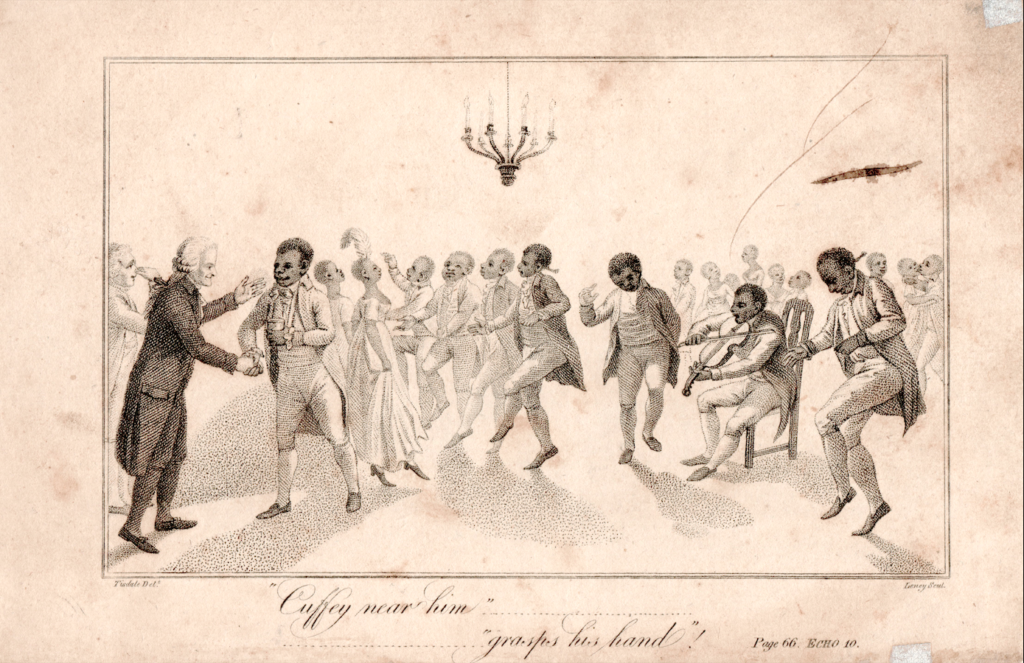

This 1808 engraving shows a satirical image of the Boston Equality Ball hosted in 1772 by Governor John Hancock. Prominently highlight is black leader and business man Paul Cuffe.

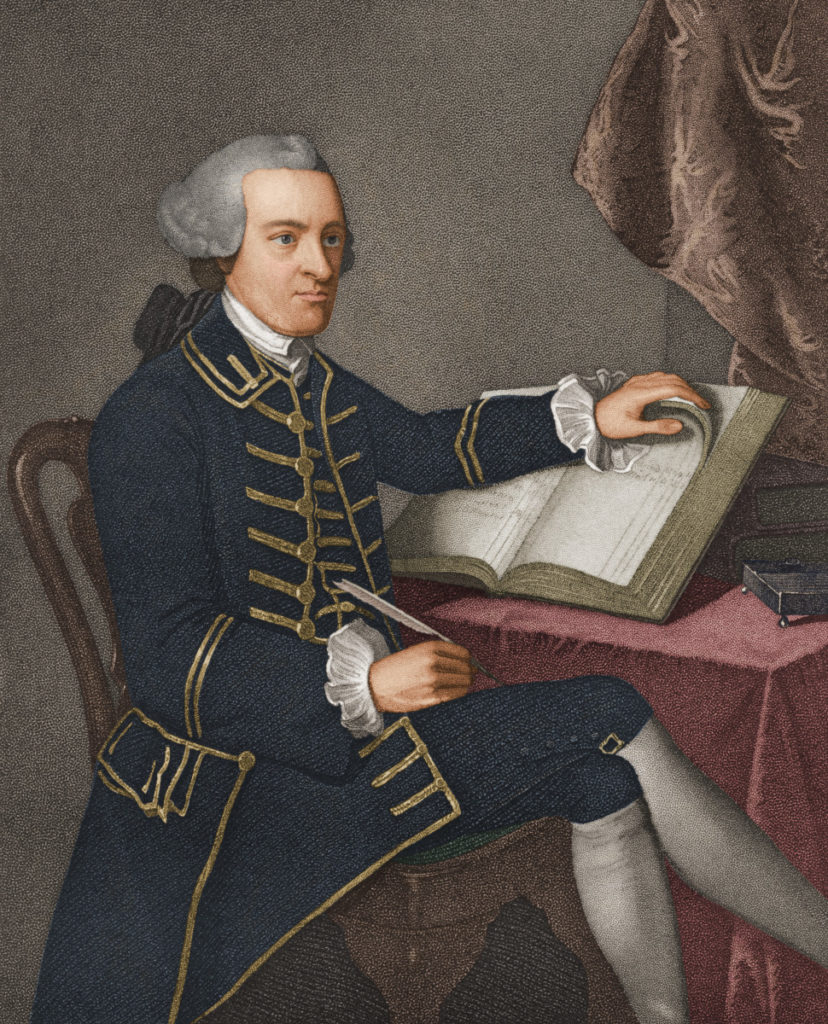

John Hancock is perhaps one of the most memorable names in American history. As president of the Continental Congress, Hancock signed his name on the Declaration of Independence in a massive, flowery script which left an indelible impression upon the minds of his countrymen. The connection was so manifest that eventually, the term “John Hancock” became synonymous with signatures, and to put your “Hancock” on something now means to sign a document. However, Hancock’s participation in advancing American rights and liberties goes well beyond his name on the Declaration.

One of the most striking displays of his commitment to the ideals of freedom happened in December of 1792 when, as Governor of Massachusetts, Hancock hosted an event to celebrate the lives and contribution of black Americans in Boston. This Equality Ball, as it was called, highlighted the participation and inclusion of African Americans in Massachusetts, specifically Boston.[1] As a well-connected merchant, Hancock was well aware that the success which Massachusetts enjoyed was in no small part due to the skill and efforts of black Americans who were expert mariners, master shipbuilders, and invaluable dock hands who were employed in those vocations.

Furthermore, at this time Massachusetts was practically the world leader concerning antislavery action. In 1780, the new Massachusetts constitution resoundingly declared that:

All men are born free and equal, and have certain natural, essential, and unalienable rights; among which may be reckoned the right of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties; that of acquiring, possessing, and protecting property; in fine, that of seeking and obtaining their safety and happiness.[2]

These words, based upon the language used by Thomas Jefferson in the Declaration of Independence, were in essence the tacit de jure abolition of slavery in the state. However, such a statement had to be enforced in order to make freedom the universal de facto condition of all inhabitants of Massachusetts. Shortly after the new constitution was ratified, black Americans went to court equipped with the new constitution to argue for the enforcement and protection of their, “natural, essential, and unalienable rights.”

Even before the Revolutionary War, black Americans had successfully used the legal system to advocate, advance, and secure their liberty and equal rights. Contrary to what people might expect, in many of the Northern states enslaved people had the equal procedural rights within the courtroom which, together with the right to sue, led many slaves to advocate for freedom through the New England government.[3] Founding Father John Adams, who never owned slaves during any portion of his life, recalled many years later that:

I was concerned in several Causes, in which Negroes sued for their Freedom before the Revolution.…I never knew a Jury, by a Verdict to determine a Negro to be a slave—They always found them free.[4]

The success of such courtroom activism was no less significant after the Revolutionary War than it was beforehand. Indeed, the black legal movement in Massachusetts predated similar activities in places on both sides of the Atlantic by nearly a full decade.[5] With the expanded legal framework provided in the 1780 constitution, black Americans in Massachusetts walked into the courtrooms with growing support for a powerful case.

In 1781, a slave by the name of Quock Walker sued his owner, Nathaniel Jennison, on the grounds of assault and battery. Represented by attorneys Levi Lincoln (who would become US Attorney General under Jefferson) and Caleb Strong (who would become Governor of Massachusetts), Walker asserted that he had been unlawfully held in bondage and beaten by Jennison and his associates.[6] Since Walker by right ought to be free, he deserved restitution for the injuries sustained. Jennison, on the other hand, argued that Walker was his slave and that he could therefore do as he pleased.

The issue between Walker and Jennison triggered several legal cases which dealt with determining what the actual status of slavery was in Massachusetts. In arguing against the legality of slavery and the inherent freedom of Walker, attorney Levi Lincoln powerfully explained:

It will then be tried by the laws of reason and revelation. Is not a law of nature that all men are equal and free? Is not the laws of nature the laws of God? Is not the law of God then against slavery?…We are all born in the same manner, have our bones clothed with the same kind of flesh—had the same breath of life breathed into us—are all under the same Gospel dispensation [and] have one common Savior.[7]

In 1783, Walker’s case reached the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court. After hearing the arguments and reviewing the case, Chief Justice William Cushing instructed the jury on matters of law, explaining that Jennison was guilty and that Walker was free because the 1780 Constitution had effectually removed any legal protections of slavery. Justice Cushing rejected the notion that slavery could now exist in a place such as Massachusetts, saying that:

Whatever usages formerly prevailed or slid in upon us by the example of others on the subject, they can no longer exist. Sentiments more favorable to the natural rights of mankind, and to that innate desire for liberty which heaven, without regard to complexion or shape, has planted in the human breast—have prevailed since the glorious struggle for our rights began. And these sentiments led the framers of our constitution of government—by which the people of this commonwealth have solemnly bound themselves to each other—to declare that all men are born free and equal; and that every subject is entitled to liberty, and to have it guarded by the laws as well as his life and property. In short…slavery is in my judgement as effectively abolished as it can be by the granting of rights and privileges wholly incompatible and repugnant to its existence. The court are therefore fully of the opinion that perpetual servitude can no longer be tolerated in our government.[8]

With this, any illusion of legal protection for slavery evaporated within Massachusetts, and by the first Federal Census in 1790 the state had completely eradicated the wicked institution.[9] Therefore, exactly fifty years before England abolished slavery Massachusetts had already legally declared all slaves to be free, making the state virtually the first political entity to do so in the modern world.

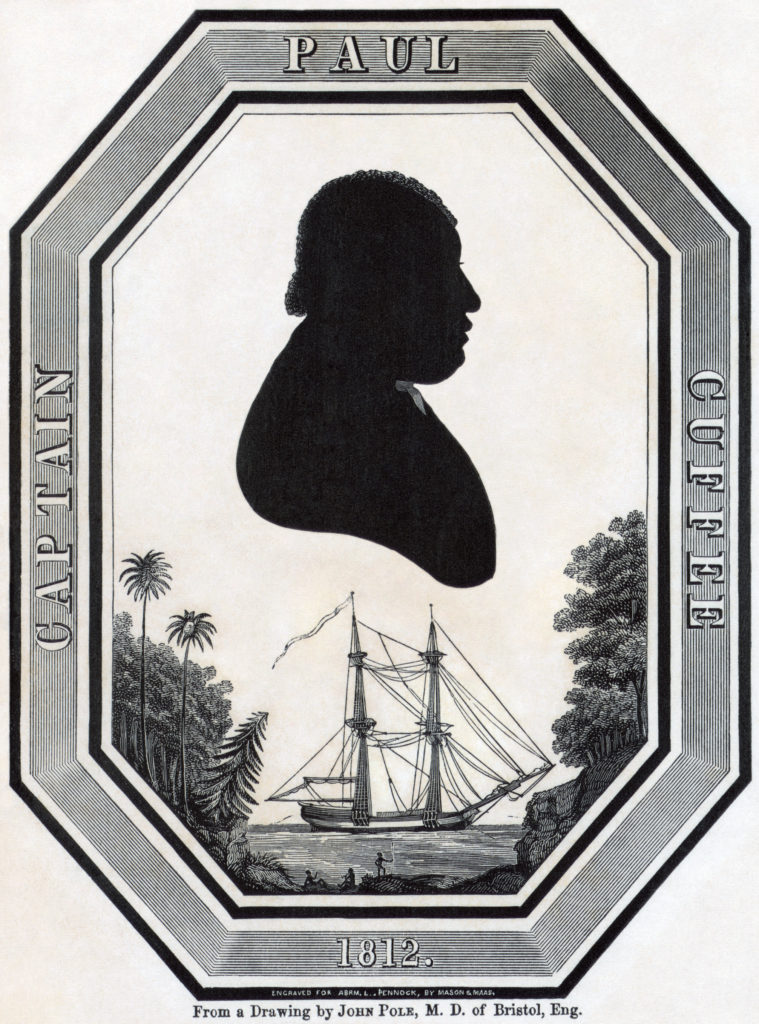

It was within this environment that John Hancock decided to celebrate the accomplishments of black Americans living in his state. One of the most prominent attendees was a gentleman named Paul Cuffe.[10] Cuffe was a rich and influential black merchant in Boston who supported American independence throughout the war as a blockade runner and was personally acquainted with Hancock. Some historians consider him to be the richest African American man in the nation during the late 1700 and early 1800s.[11] In total, he owned, either in whole or in part, a fleet of ten ships.[12] In addition to his efforts in industry and commerce, he also worked tirelessly to advance civil rights protections for black Americans.[13]

Not everyone was pleased with Hancock’s decision to host an Equality Ball with men like Paul Cuffe in attendance. The next month, a newspaper published a sneering satirical poem attacking Hancock, the Equality Ball, and Cuffe in derisive terms.[14] The poet condemns Hancock for being overly, “fir’d with patriot rage,” causing him to be too, “prompt to assert the rights of man.”[15]In a false hagiographic style, the author sarcastically derides Hancock and the event saying:

Behold him to his splendid hall / The Noble sons of Afric call: / While as the sable bands advance, / With frolic mien, and sportive dance, / Refreshing clouds of rich perfume / Are wafted o’er the spacious room. / With keen delight the Sage surveys / Their graceful tricks, and winning ways; / Their tones enchanting raptur’d hears, / More sweet than music of the spheres; / And as he breathes the fragrant air, / He deems that Freedom’s self dwells there. / While Cuffey near him takes his stand, / Hale-fellow met, and grasps his hand— / With pleasure glistening in his eyes, / “Ah! Massa Gubbernur!” he cries, / “Me grad to see you, for de peeple say / “You lub de Neegur better dan de play.”[16]

The closing line references the fact that Hancock had recently imposed limitations upon performance theaters on the grounds of the ill-effects they were having upon people’s morals by encouraging or facilitating bad deeds. From the author’s perspective, it seemed preposterous that Hancock should claim to guard against bad morals in the theater while at the same time hosting a celebratory ball for black Americans. Although the poem was originally published anonymously, it was reprinted in 1808 by Richard Aslop alongside the engraving now housed in the American Journey Experience.[17] In an ironic twist of fate, almost the only reason why we know of Hancock’s 1792 Equality Ball is because of the poem attacking the event.

[1] Joanne Melish, Disowning Slavery: Gradual Emancipation and ‘Race’ in New England, 1780-1860 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1998), 168-169. Here.

[2] “The Constitution or Frame of Government for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts,” The Perpetual Laws of the Common wealth of Massachusetts, From the Establishment of its Constitution, in the Year 1780, To the End of the Year 1800 (Boston: I. Thomas and E. T. Andrews, 1801), 1.19. Here.

[3] Arthur Zilversmit, The First Emancipation: The Abolition of Slavery in the North (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1968), 19.

[4] John Adams in, Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society (Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1877), 401-402.

[5] Chernoh Sesay, Jr., “The Revolutionary Black Roots of Slavery’s Abolition in Massachusetts,” The New England Quarterly, Vol. 87, No. 1 (March 2014), 101.

[6] A. Leon Higginbotham, Jr., In the Matter of Color: Race and the American Legal Process, The Colonial Period (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1978), 91. Here.

[7] Levi Lincoln quoted in, A. Leon Higginbotham, Jr., In the Matter of Color: Race and the American Legal Process, The Colonial Period (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1978), 93. Here.

[8] William Cushing, quoted in, John Cushing, “The Cushing Court and the Abolition of Slavery in Massachusetts: More Notes on the ‘Quock Walker Case’” The American Journal of Legal History Vol. 5, No. 2 (April 1961): 133.

[9] The American Almanac and Repository of Useful Knowledge for the Year 1858 (Boston: Crosby, Nicholas, and Company, 1858), 214.

[10] James G. Baske, Amazing Grace: An Anthology of Poems about Slavery, 1660-1810 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002), 478-479; Joanne Melish, Disowning Slavery: Gradual Emancipation and ‘Race’ in New England, 1780-1860 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1998), 168-169.

[11] “Paul Cuffe,” Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience, edts. Kwame Appiah and Henry Gates, Jr.,(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 2.283.

[12] “Paul Cuffe,” Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience, edts. Kwame Appiah and Henry Gates, Jr.,(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 2.283.

[13] George Washington Williams, History of the Negro Race in America From 1619 to 1880 (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1883), 2.125-127. Here.

[14] James G. Baske, Amazing Grace: An Anthology of Poems about Slavery, 1660-1810 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002), 478-479.

[15] “Hartford, January 21st, 1793,” Richard Alsop, The Echo, With Other Poems (New York: The Porcupine Press, 1807), 66. Here.

[16] “Hartford, January 21st, 1793,” Richard Alsop, The Echo, With Other Poems (New York: The Porcupine Press, 1807), 66. Here.

[17] “Hartford, January 21st, 1793,” Richard Alsop, The Echo, With Other Poems (New York: The Porcupine Press, 1807), 65-66, engraving after 94. Here.