Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) remains one of the most recognizable Founding Fathers from our nation’s origins and for good reason. In addition to being a leader in the struggle for American independence, Franklin was a prominent publisher, influential writer, noted scientist, architect of the American postal system, educational pioneer, founder of the first hospital in America, and staunch abolitionist. His role in shaping the direction in which the young nation grew has led some to consider Franklin “the first American.”1

This document in the American Journey Experience Collection was signed by Franklin while he served as the sixth president of the Supreme Executive Council of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania from 1785 to 1788 after being unanimously elected.2 Franklin had just returned from serving in France as an American minister, and Pennsylvania looked to the aged stateman to help unify an extremely contentious political situation which potentially threatened to pull the state apart.3 Despite being almost 80 years old and not wanting to actively continue in politics, Franklin agreed to serve as President. He explained to some friends that:

I had on my return some right, as you observe, to expect repose; and it was my intention to avoid all public business. I had not the firmness enough to resist the unanimous desire of my country folks; and I find myself harnessed again in their service for another year. They engrossed the prime of my life. They have eaten my flesh, and seem resolved now to pick my bones.4

The 1776 Pennsylvania Constitution created the Pennsylvania Supreme Executive Council which functioned as the colony’s executive branch of government from 1777 to 1790.5 The council consisted of twelve members, one from each county, with two chosen by the Council to act as president and vice president.6 As the figurehead of the executive branch for the Pennsylvania state, the President of the Supreme Executive Council was Commander-in-Chief of its military forces. This meant that Franklin was ultimately responsible for handling issues regarding Pennsylvania’s soldiers and navigating the aftermath of the Revolutionary War in that state.7 Upon the outbreak of open hostilities in 1775, the issue of assembling a Continental Army to match the world-class British military became the most pressing concern. There had been no national army before and each state had their own methods of forming militias to protect local areas as the need arose. Suddenly, a professional army was needed for an indefinite period of time to confront threats across a wide theater of war. This naturally caused significant difficulties on national, state, and local levels. The leadership of George Washington as commanding general provided necessary leadership on the national front, but the responsibility of furnishing his army with troops fell upon the states who each had to provide a certain number as requested by Congress.8

As Pennsylvania attempted to meet the required troop quota, they offered bounties for three years of military service. The troops who signed up to serve from 1777 to 1780 were to be paid using the new continental bills of credit which, “had no other basis than the faith of the public in the ultimate success of the American cause.”9 Unsurprisingly, the currency was radically unstable and soon lost a substantial amount of its value meaning that the soldiers were only receiving pennies on the dollar. The paper money issued by Congress became so devalued that a popular expression at the time was that things were, “not worth a Continental.”10 The overall supply situation was so desperate during the winter at Valley Forge in 1777, Washington reported to the President of Congress two days before Christmas that:

I am now convinced beyond a doubt, that unless some great and capital change suddenly takes place in that line this Army must inevitably be reduced to one or other of these three things. Starve—dissolve—or disperse in order to obtain subsistence in the best manner they can. Rest assured, Sir, this is not an exaggerated picture.…We have by a field return this day made, no less than 2898 men now in camp unfit for duty because they are barefoot and otherwise naked.11

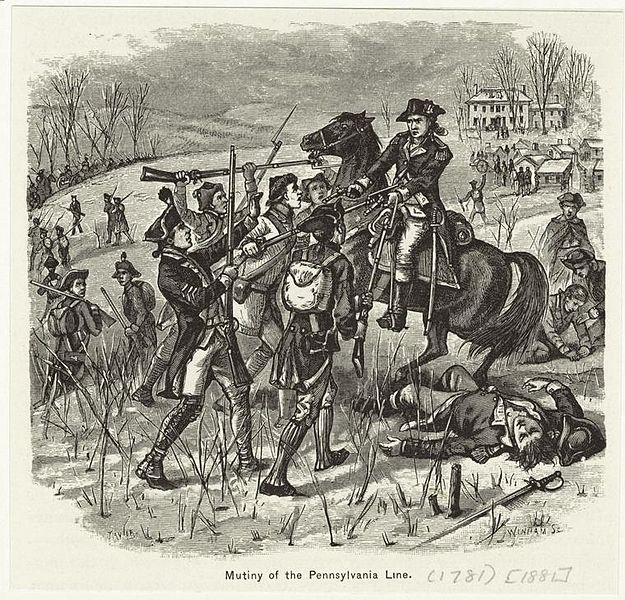

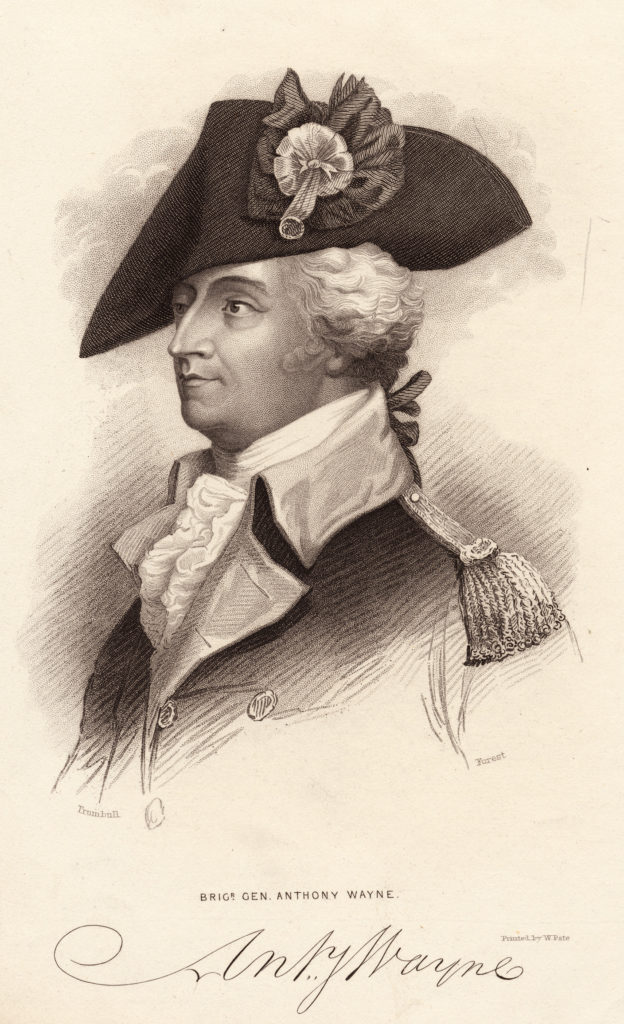

Due to reoccurring failures in supplying the army, the Continental Congress abdicated control of supplying the military in 1779 and instead set quotas for the states to provide but failed to establish any method of getting said quotas to the armies.12 This and numerous other problems led to even more issues, and several mutinies occurred on account of the severe lack of food, supplies, and pay.13 The situation for the Pennsylvania line was even worse in many respects. On top of the general vicissitudes of war and the lack of supplies for the army, the state of Pennsylvania was not appropriately compensating the soldiers who signed three-year contracts in 1777. While states such as New Jersey offered enlistees some $250, and Massachusetts promised $500, the “three-year men” from Pennsylvania had only been offered a measly $20.14 Furthermore, their enlistment bounties were nearly worthless because the currency had depreciated so drastically. The troops were, in the words of their commanding officer General Anthony Wayne, “poorly clothed, badly fed, and worse paid.”15

The scene was ripe for mutiny as the government failed to provide even the most basic necessities or just compensation. On December 31st, 1780, in the midst of New Year’s Eve celebrations, many of the three-year men packed their gear and began to leave for home. Some of the officers stopped them, however, saying that they were required to remain in the army until the war was over.16 This proved to be too much for the beleaguered and already mistreated Pennsylvania line. After a brief confrontation, the soldiers-turned-mutineers decided to demand restitution for their grievances. In explaining the situation, General Washington, noted that the grievances of the troops were clearly justified, saying that, “The aggravated calamities and distresses that have resulted from the total want of pay for nearly twelve months, the want of clothing at a severe season, and not unfrequently the want of provisions, are beyond description.”17

General Wayne and a handful of officers were permitted to travel with the mutineer army and served as mediators between them and the government. Furthermore, General Wayne sought to ensure that the troops did not defect to the British.18 The soldiers, however, reassured their commanding officer that, “it was not their intention, and they would hang any man who would attempt it, and for that, if the enemy should out in consequence of this revolt, they would turn back and fight them.”19 The spirit of ’76 certainly still animated the soldiers, but ideology alone was insufficient—the government of Pennsylvania had to uphold their side of things. On January 4, 1781, the body of troops listed their demands. In short, they only asked that the men whose enlistment periods were up would be given their due pay and to be discharged as agreed upon. For the troops who remained, they asked simply that they be provided clothes, pay, and that no one would be punished for the mutiny.20

With the arrival of Joseph Reed who was then the President of the Supreme Executive Council at that time, negotiations proceeded fairly smoothly and without any further escalation. Some British agents attempted to infiltrate the mutineers’ camp and persuade them to defect, but they were soon caught and turned over to the state of Pennsylvania.21 Ultimately, President Reed and General Wayne agreed with the soldiers that the officers had been wrong to prevent the men who had fulfilled their enlistments to leave and that they ought to be properly compensated for their service.22 In total, General Wayne reported that some 1,250 troops were entitled to their discharge.23

In order to help ameliorate the problems which had caused the mutiny in the first place, Pennsylvania began passing laws which would counteract the rapid depreciation of the continental currency. Even as late as 1783, laws were being passed to fix the depreciation issue because the actions thus far taken had, “not answered all the good purposes thereby intended, and…the funds established for the redemption of the certificates granted for the depreciation of pay…have not proved sufficiently productive.”24 The state issued certificates acknowledging that soldiers would be paid an amount to neutralize the depreciated value, but could not immediately pay off these amounts. Every additional year, the depreciation certificate would accrue interest similar to a bond, meaning that Pennsylvania had to pass laws to raise even more money to pay not only the depreciation certificates but also the interest on them.25

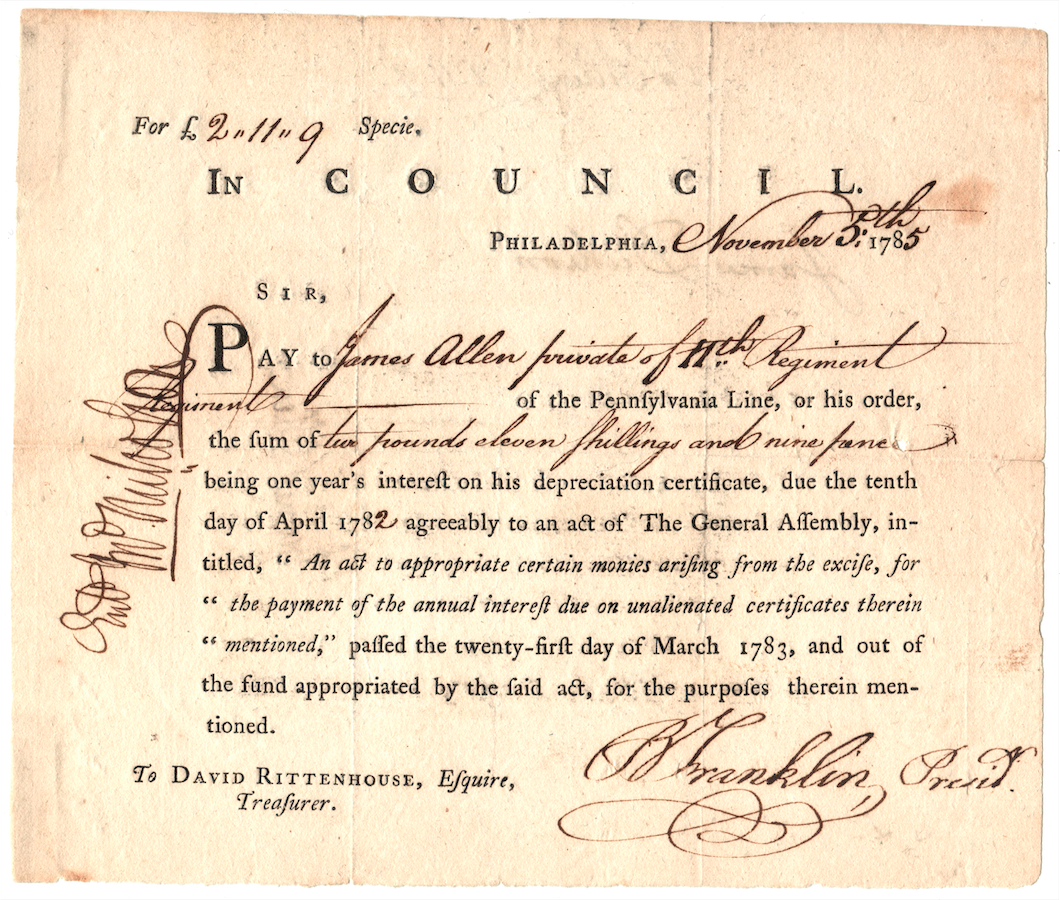

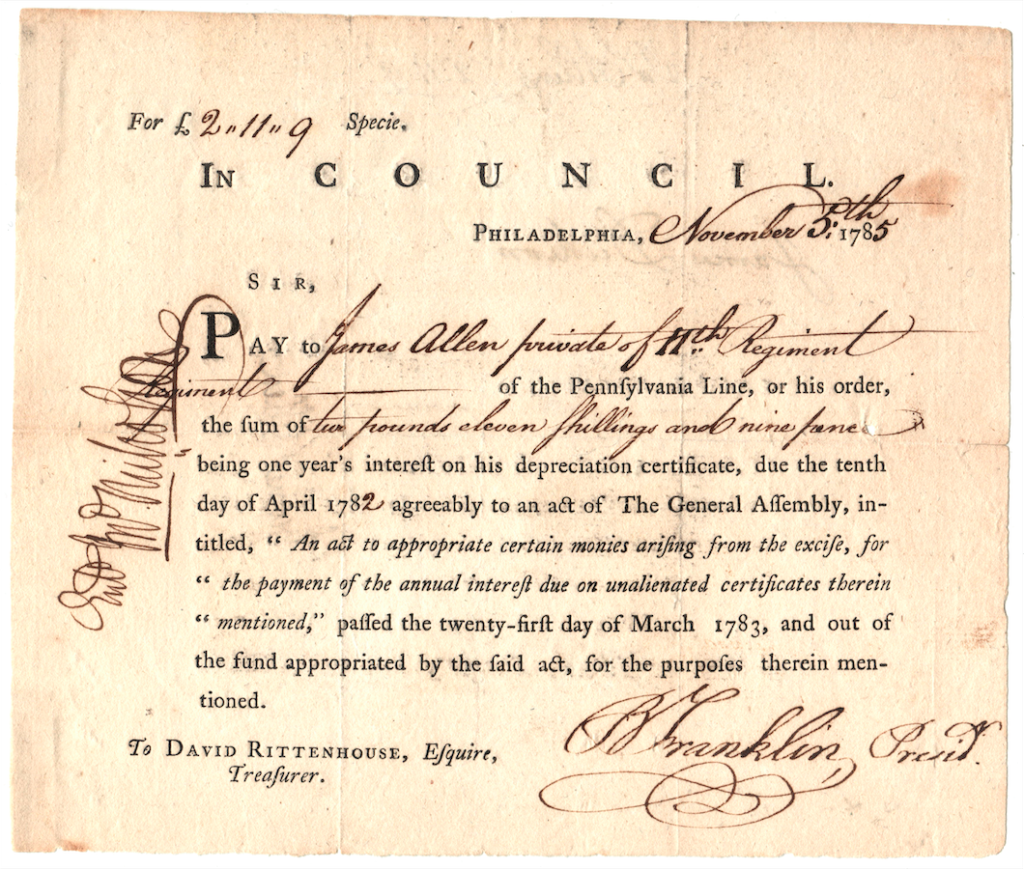

The American Journey Experience is home to one such interest payment on a soldier’s depreciation certificate. Even when Franklin became president in 1785, Pennsylvania was still paying yearly interest according to the 1783 law. In this example, Private James Allen of the 11th Regiment in the Pennsylvania Line is to be paid two pounds, eleven shillings, and nine pence in specie instead of the continental fiat or other printed currency. In full, the document reads:

In Council. Philadelphia, November 25th, 1785.

Sir,

Pay to James Allen private of 11th Regiment of the Pennsylvania Line, or his order, the sum of two pounds eleven shillings and nine pence being one year’s interest on his depreciation certificate, due the tenth day of April 1782 agreeably to an act of The General Assembly, intitled, “An act to appropriate certain monies arising from the excise, for the payment of the annual interest due on unalienated certificated therein mentioned,” passed the twenty-first day of March 1783, and out of the fund appropriated by the said act, for the purposes therein mentioned.

To David Rittenhouse, Esquire, Treasurer.

B. Franklin, Presid. [Hand Signed]

1. H. W. Brands, The First American: The Life and Times of Benjamin Franklin (New York: Anchor Books, 2000).

2. James Parton, Life and Times of Benjamin Franklin (New York: Mason Brothers, 1864), 2.543. Here.

3. James Parton, Life and Times of Benjamin Franklin (New York: Mason Brothers, 1864), 2.541-542. Here.

4. Benjamin Franklin, “To John Bard and Mrs. Bard,” November 14, 1785, The Works of Benjamin Franklin (Boston: Charles Tappan, 1844), 10.239. Here.

5. “The Constitution of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania,” 1776, The Constitutions of the Several Independent States of America (Philadelphia: J. Stockdale, 1782), Chapter 2, Sect. 3. Here. .

6. “The Constitution of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania,” 1776, The Constitutions of the Several Independent States of America (Philadelphia: J. Stockdale, 1782), Chapter 2, Sect. 19. Here..

7. “The Constitution of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania,” 1776, The Constitutions of the Several Independent States of America (Philadelphia: J. Stockdale, 1782), Chapter 2, Sect. 20. Here.

8. Emory Upton, The Military Policy of the United States (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1904), 26-27. Here.

9. Emory Upton, The Military Policy of the United States (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1904), 3, 50. Here.

10. Erna Risch, Supplying Washington’s Army (Washington: Center of Military History United States Army, 1981), 20. Here.

11. George Washington, “To Henry Laurens,” December 23, 1777, Founders Online (accessed February 8, 2022): https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-12-02-0628.

12. Erna Risch, Supplying Washington’s Army (Washington: Center of Military History United States Army, 1981), 89. Here.

13. Emory Upton, The Military Policy of the United States (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1904), 61. Here.

14. For Connecticut and Massachusetts see, George Bancroft, A History of the United States, From the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1874), 10.206, 234, here;

15. Anthony Wayne quoted in, Charles Stille, Major-General Anthony Wayne and the Pennsylvania Line in the Continental Army (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1893), 240. Here.

16. Charles Stille, Major-General Anthony Wayne and the Pennsylvania Line in the Continental Army (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1893), 239. Here.

17. George Washington, “To Meshech Weare, President of New Hampshire,” January 5, 1781, The Writings of George Washington (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1847), 7.352. Here.

18. Anthony Wayne quoted in, Charles Stille, Major-General Anthony Wayne and the Pennsylvania Line in the Continental Army (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1893), 243. Here.

19. John B. Reeves, “Extracts from the Letter-Books of Lieutenant Enos Reeves, of the Pennsylvania Line,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography (Philadelphia: The Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1897), 21.75. Here.

20. Anthony Wayne quoted in, Charles Stille, Major-General Anthony Wayne and the Pennsylvania Line in the Continental Army (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1893), Here.

21. Daniel Humphreys, “No. 3481. The Pennsylvania Line Mutiny. British Emissaries Who Tried to Seduce the Troops, Turned Over to Lord Stirling as Spies,” in Public Papers of George Clinton, First Governor of New York (Albany: J. B. Lyon Company, 1902), 6.564. Here.

22. Anthony Wayne quoted in, Charles Stille, Major-General Anthony Wayne and the Pennsylvania Line in the Continental Army (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1893), 244. Here.

23. Anthony Wayne quoted in, Charles Stille, Major-General Anthony Wayne and the Pennsylvania Line in the Continental Army (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1893), 245. Here.

24. “An Act to Appropriate Certain Monies Arising from the Excise, for the Payment of the Annual Interest Due on Unalienated Certificated Therein Mentioned,” March 21, 1783, The Statutes at Large of Pennsylvania from 1682 to 1801 (Harrisburg: Harrisburg Publishing Company, 1906), 11.100. Here

25. “An Act to Appropriate Certain Monies Arising from the Excise, for the Payment of the Annual Interest Due on Unalienated Certificated Therein Mentioned,” March 21, 1783, The Statutes at Large of Pennsylvania from 1682 to 1801 (Harrisburg: Harrisburg Publishing Company, 1906), 11.100-101. Here.