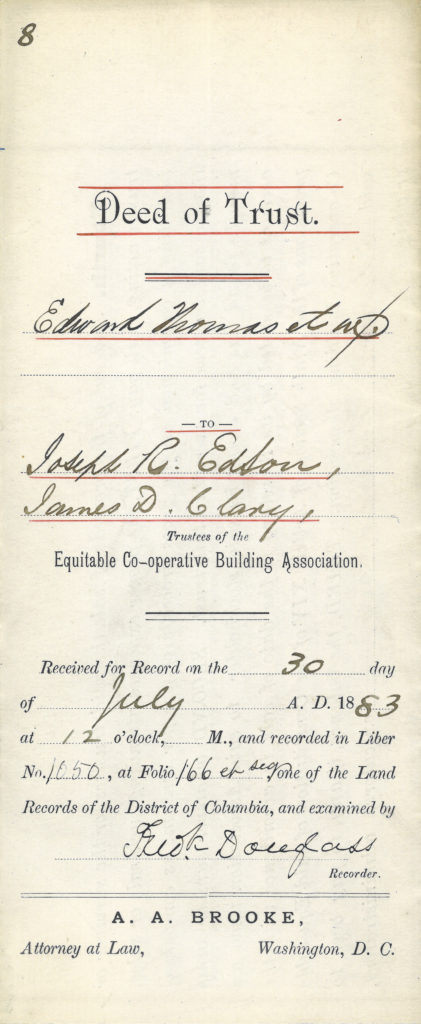

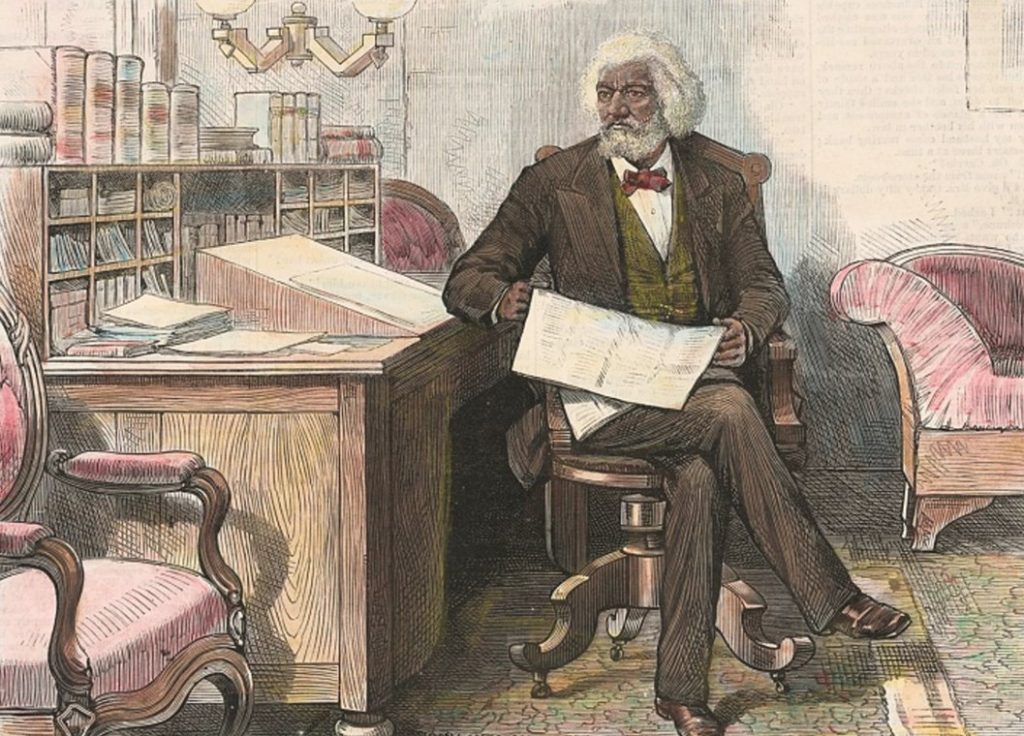

Pictured above is a “Deed of Trust” for the “Equitable Co-operative Building Association”. After Douglass’ tenure as the U.S. Marshall for Washington D.C., he served as D.C.’s first Recorder of Deeds from 1881 -1886. The deed is recording an agreement between Edward Komas etm, Joseph R. Edson, and James D. Clary.

“If there is no struggle, there is no progress. Those who profess to favor freedom, and yet depreciate agitation, are men who want crops without plowing up the ground. They want rain without thunder and lightning. They want the ocean without the awful roar of its many waters. This struggle may be a moral one; or it may be a physical one; or it may be both moral and physical; but it must be a struggle.”[1]

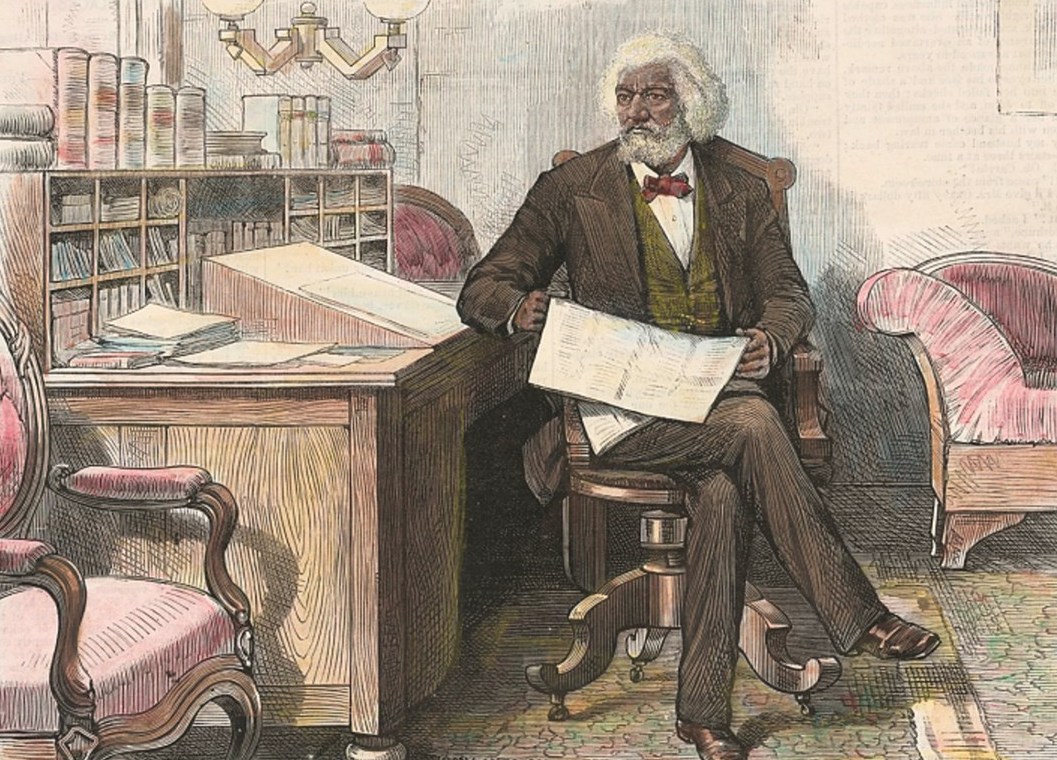

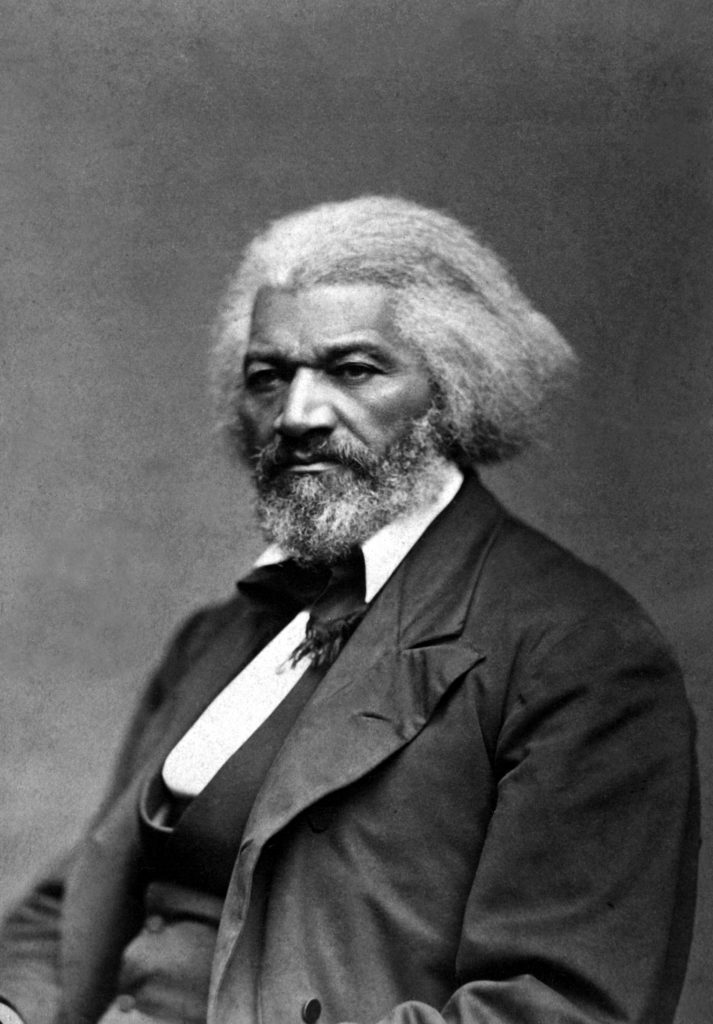

The story of Frederick Douglass is unique among his contemporaries as it stands as an anomaly in the theater of suffering within the human experience. As a child, Douglass witnessed the many evils of slavery, and his personal blows with unimaginable verbal, physical, and emotional abuse were enough to break any man. However, Providence engrained a conviction deep within his soul for freedom more powerful than any instrument of torture fashioned against him.[2] From slave to statesmen, Douglass transcended the immense plight of his upbringing to grasp an echelon of influence and leadership largely unknown to people of color at that time. From his escape of slavery, to the formation of his successful abolitionist newspaper, The North Star, and his meetings with Abraham Lincoln, he was forged for such a time as this. His sufferings would endow him with the fortitude needed to lead a movement that would change a nation, and forever impact the world.

Douglass was born in Cordova, Maryland, February 1817 or 1818. Uncertainty regarding one’s day of birth was common for those born into slavery.[3] He never knew his father but speculated it could have been his first master. As for his mother, his recollection was faint:

The opinion was…whispered that my master was my father; but of the correctness of this opinion, I know nothing. … My mother and I were separated when I was but an infant. … It is a common custom, in the part of Maryland from which I ran away, to part children from their mothers at a very early age. … I do not recollect of ever seeing my mother by the light of day. She was with me in the night. She would lie down with me, and get me to sleep, but long before I waked she was gone.[4]

He would never see his mother again after the age of seven.[5] Douglass was eventually separated from his grandparents and sent to the Wye House Plantation. It was here that he, at only six years old, would first witness the horrors of slavery from the slit of a closet in which he hid. Hester, Douglass’ aunt, left the plantation in the evening time when the master, Aaron Anthony, had requested her presence. She was apprehended, and worse, caught with another slave she was forbidden to see. The ensuing punishment, as Douglass recalled, was swift and brutal:

Before he commenced whipping Aunt Hester, he took her into the kitchen, and stripped her from neck to waist, leaving her neck, shoulders, and back entirely naked…. After crossing her hands, he tied them with a strong rope, and led her to a stool under a large hook in the joist, put in for the purpose…. Her arms were stretched up at their full length, so that she stood upon the ends of her toes…. And after rolling up his sleeves, he commenced to [whip] her, and soon warm, red blood (amid heart-rending shrieks from her, and horrid oaths from him) came dripping to the floor.[6]

The scene forever scarred young Douglass, and would serve as a terrible precedent for what he would eventually endure. After the death of the plantation’s overseer Aaron Anthony, he was given to Lucretia Auld, who then sent him to her brother-in-law Hugh Auld, in Baltimore, Maryland. Douglass was elated about the move, saying:

I was probably between seven or eight years old when I left Colonel Lloyd’s plantation. I left it with joy. I shall never forget the ecstasy with which I received the intelligence that my old master (Anthony) had determined to let me go to Baltimore….I received this information about three days before my departure. They were the happiest days I ever enjoyed.

Hugh’s wife, Sophia, took fondly to young Douglass. He later recounted that “Her face was made of heavenly smiles, and her voice of tranquil music,” and possessed “the kindest heart and finest feelings.” [7] She took notice of his lack of education and began to teach him the alphabet. After Douglass mastered his first lesson, she showed him how to spell three- and four-letter words. At that point in his instruction, Mr. Auld found out what Sophia was doing, and reprimanded her. What he would say next would forever change Douglass:

If you give a n

—-ran inch, he will take [a mile]. A n—-r should know nothing but to obey his master – to do as he is told to do. Learning would spoil the best n—-r in the world. Now, if you teach that n—-r how to read, there would be no keeping him. It would forever unfit him to be a slave [emphasis added].[8]

Hearing these words awakened a burning sentiment long stored in Douglass’ heart, that, before, was only adolescent suspicion. His liberty would be won through literacy, with literacy, obtain knowledge, and through knowledge, freedom:

From that moment, I understood the pathway from slavery to freedom….. [While] I was saddened by the thought of losing the aid of my kind mistress, I was gladdened by the invaluable instruction which, by the merest accident, I had gained from my master.[9]

It was not long after that day Sophia turned from her benevolent ways. She joined in suppressing Douglass’ education, and eventually became worse than her husband. However, Douglass was purposed to continue where Sophia left off, and determined to prove his master true, that, “Mistress, in teaching me the alphabet, had given me the inch, and no precaution could prevent me from taking the [mile].”[10] His most effective self-education technique came from bartering with poor white children in his neighborhood, who helped him read in exchange for bread.[11]

In 1832, Thomas Auld retrieved Douglass from Baltimore and realized that city life had substantially changed him. Auld claimed it had ruined him for any of his purposes on the farm. He was infuriated with his perceived misfortune, and began to be violent with Douglass, giving him numerous severe beatings.[12] In 1833, after nine months of mistreatment, Auld was “resolved to put me out… to be broken,” and sent Douglass to Edward Covey.[13]

Covey developed a reputation for “breaking young slaves”, and he lived up to this evil skill.[14] Douglass recalled that he had been at his new home for one week “before Mr. Covey gave me a severe whipping, cutting my back, causing the blood to run, and raising the edges of my flesh as large as my little finger.”[15] Douglass records being whipped nearly every week for six months, and made to work in weather conditions unfit for any person to be in.[16] The hope Douglass had in his heart for freedom began to fade. At times, he envied the lives of more ignorant slaves, or even animals, because most of the former did not know of a life outside a plantation, and the latter were free to roam the earth.[17] His beatings and mistreatments would continue until one fateful day in August 1833.

Douglass had been ordered to tend to Covey’s horses in the stable when, unexpectedly, Covey attempted to bind Douglass by his feet and subject him to be beating. Douglass, full of fury, opted to defend himself for the first time. This seminal moment in Douglass’ life was recorded by him telling the reader “You have seen how a man was made a slave; you shall now see how a slave was made a man.” The fight ensued:

“I resolved to fight; and suiting my action to the resolution, I seized Covey hard by the throat; and as I did so, I rose. He held on to me, and I to him. My resistance was so entirely unexpected, that Covey seemed taken all aback. He trembled like a leaf. This gave me assurance, and I held him uneasy, causing the blood to run where I touched him with the ends of my fingers.”[18]

Covey and Douglass fought for two hours, which consisted mostly of Covey being summarily beaten. Douglass recorded that by the end of the fight, Covey drew not an ounce of blood from him. For the next six months of his stay at the plantation, Covey never touched Douglass in anger again.[19] From that moment on, Douglass harbored a renewed fire in his soul for freedom, noting that however long he was a slave in form, he would never be a slave in fact.[20]

On Sep. 3rd, 1838, Douglass fled his plantation to a haven for escaped slaves started by abolitionist David Ruggles in New York, forever ending his captivity and entering a new life:

From my earliest recollection, I date the entertainment of a deep conviction that slavery would not always be able to hold me within its foul embrace; and in the darkest hours of my career in slavery, this living word of faith and spirit of hope departed not from me, but remained like ministering angels to cheer me through the gloom. This good spirit was from God, and to him I offer thanksgiving and praise.[21]

Douglass went on to become the icon for abolition of slavery in America. He traveled the nation speaking about his experience as a slave, and how the evils of slavery are against the very promises enshrined in the Declaration of Independence, and Constitution:

“I have said that the Declaration of Independence is the ring-bolt to the chain of your nation’s destiny; so, indeed, I regard it. The principles contained in that instrument are saving principles. Stand by those principles, be true to them on all occasions, in all places, against all foes, and at whatever cost.” He continued, “the Constitution is a GLORIOUS LIBERTY DOCUMENT [sic]. Read its preamble, consider its purposes….. Now, take the Constitution according to its plain reading, and I defy the presentation of a single pro-slavery clause in it. On the other hand it will be found to contain principles and purposes, entirely hostile to the existence of slavery [emphasis added].”[22]

Though Douglass started life as a slave, he ended it as not only a free man, but an influential voice to numerous presidents including Abraham Lincoln. At the onset of the Civil War, Douglass acted on behalf of black troops to Lincoln, advocating for fair treatment of colored soldiers in the Union Army.[23] In the years after the Union victory, he was a staunch fighter for laws enacting civil rights and universal suffrage. His greatest legislative accomplishments were helping to usher in the 13th, 14th, and 15th, amendments to the U.S. Constitution.[24]

[1] Frederick Douglass. Two Speeches, by Frederick Douglass; One on West India Emancipation, delivered at Canandaigua, Aug. 4th, and the Other on the Dred Scott Decision, Delivered in New York, on the Occasion of the Anniversary of the American Abolition Society, May, 1857. United States: C.P. Dewey, printer, American Office, 1857. 22 Here

[2] Frederick Douglass (1851). Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave. Written by himself (6 ed.). London: H.G. Collins. 31 Here

[3] Frederick Douglass (1851). Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave. Written by himself (6 ed.). London: H.G. Collins. 1 Here

[4] Frederick Douglass (1851). Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave. Written by himself (6 ed.). London: H.G. Collins. 10 Here

[5] Frederick Douglass (1851). Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave. Written by himself (6 ed.). London: H.G. Collins. 11 Here

[6] Frederick Douglass (1851). Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave. Written by himself (6 ed.). London: H.G. Collins. 14 Here

[7] Frederick Douglass (1851). Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave. Written by himself (6 ed.). London: H.G. Collins. 34-35 Here

[8] Frederick Douglass (1851). Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave. Written by himself (6 ed.). London: H.G. Collins. 35 Here

[9] Frederick Douglass (1851). Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave. Written by himself (6 ed.). London: H.G. Collins. 36 Here

[10] Frederick Douglass (1851). Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave. Written by himself (6 ed.). London: H.G. Collins. 39 Here

[11] Frederick Douglass (1851). Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave. Written by himself (6 ed.). London: H.G. Collins. 39 Here

[12] Frederick Douglass (1851). Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave. Written by himself (6 ed.). London: H.G. Collins. 54-55 Here

[13] Frederick Douglass (1851). Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave. Written by himself (6 ed.). London: H.G. Collins. 54-55 Here

[14] Frederick Douglass (1851). Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave. Written by himself (6 ed.). London: H.G. Collins. 54-55 Here

[15] Frederick Douglass (1851). Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave. Written by himself (6 ed.). London: H.G. Collins. 55-56 Here

[16] Frederick Douglass (1851). Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave. Written by himself (6 ed.). London: H.G. Collins. 57 Here

[17] Frederick Douglass (1851). Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave. Written by himself (6 ed.). London: H.G. Collins. 41 Here

[18] Frederick Douglass (1851). Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave. Written by himself (6 ed.). London: H.G. Collins. 66 Here

[19] Frederick Douglass (1851). Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave. Written by himself (6 ed.). London: H.G. Collins. 66-67 Here

[20] [20] Frederick Douglass (1851). Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave. Written by himself (6 ed.). London: H.G. Collins. 68 Here

[21] Frederick Douglass (1851). Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave. Written by himself (6 ed.). London: H.G. Collins. 34 Here

[22] Frederick Douglass, Oration, Delivered in Corinthian Hall, Rochester. (Accessed Feb. 22, 2022) Here

[23] National Park Service, Frederick Douglass, (Accessed Feb. 22, 2022) Here

[24] National Park Service, Frederick Douglass, (Accessed Feb. 22, 2022) Here